The Greentree Estate is as much a piece of Long Island history as the family who lived in it

While so much of Manhasset in the 1920s was lost to industrialization and the advancement to modernity, there are a few precious jewels that have weathered the storm of a new century. Greentree was the home of the prominent Whitney family, known for their business enterprises, social prominence, wealth and philanthropy.

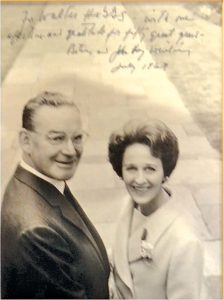

A third generation worker on the estate after his father and grandfather, Chris Hobbs has a special connection to Greentree, and his passion for history and gratitude is not lost on the Whitneys and all they left behind.

A Whitney family tree

American businessman Oliver Hazard Payne was born in 1839. Throughout his lifetime, Hazard Payne was an organizer of the American Tobacco trust, assisted with the formation of U.S. Steel, and was affiliated with Standard Oil, earning him the title of one of the 100 wealthiest Americans. Upon his death in 1917 with no children, Hazard Payne left $63 million ($1.3 billion in 2019 dollars) and his estate, Greenwood Plantation in Georgia, to his nephew, William Payne Whitney.

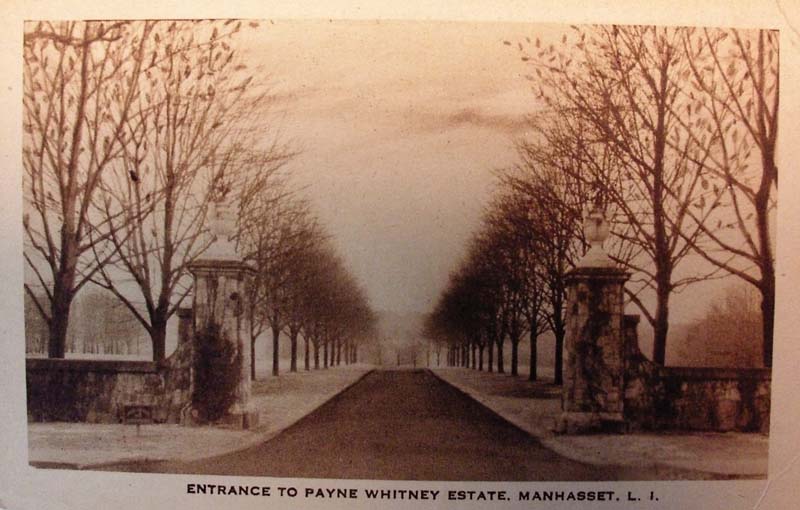

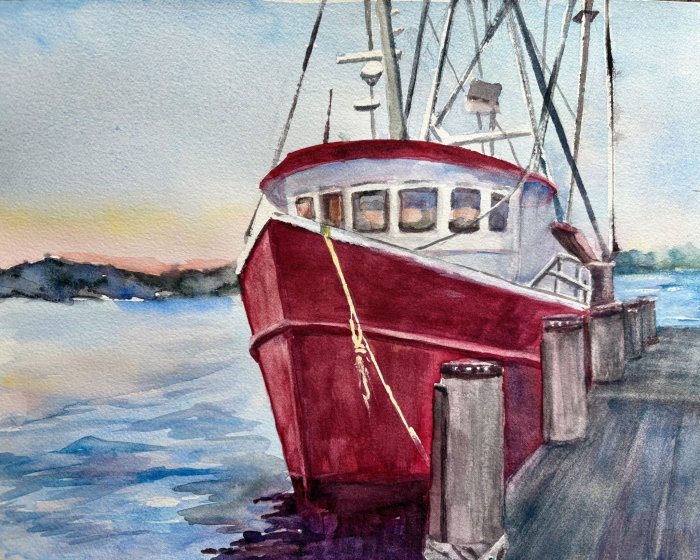

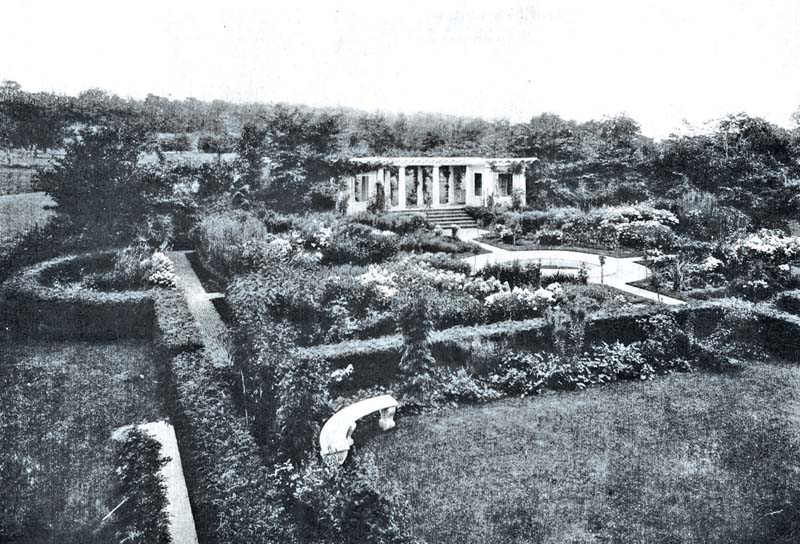

Payne Whitney married Helen Hay, the sister of his Yale roommate. As it was common to give a home to a new wife during that time, Payne Whitney built Greentree Estate in Manhasset for Helen as a wedding gift in 1904.

“The estate was made by combining five large farms and building a modest country house,” says Hobbs. “When developing the estate, Payne Whitney purchased a stained glass window in France that he had planned on adding to a chapel on the Greentree estate. After forgoing his plan, the window was donated to Christ Church (1802) in Manhasset where it resides today.”

Payne Whitney and Helen had two children; Joan Whitney Payson (1903-1975) and John Hay “Jock” Whitney (1904-1982). Joan, a sports enthusiast, would later become the first owner of the New York Mets. And Jock would become perhaps the most prominent Whitney in the history of the family, accomplishing more than his contemporaries could have imagined.

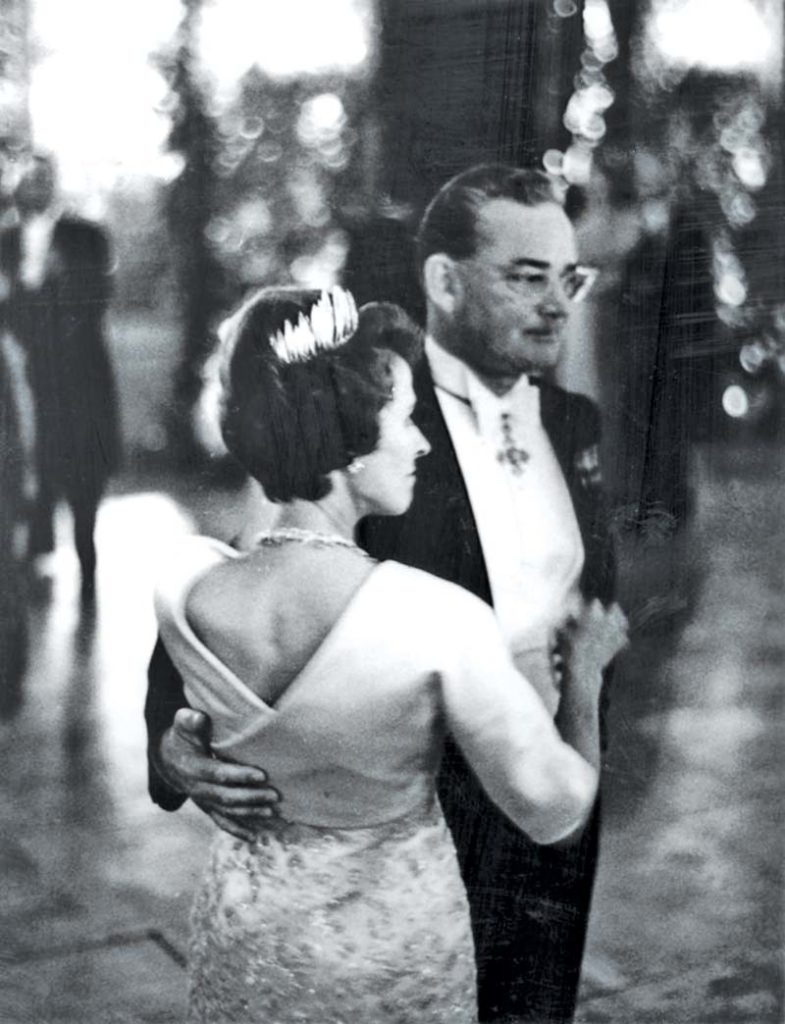

Jock’s first marriage was to Mary Elizabeth Altemus (known as Liz Whitney) and lasted from 1931 to 1940. In 1942, he married Betsey Cushing Roosevelt, the former daughter-in-law of President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Jock adopted her two daughters from her previous marriage. According to Hobbs, who has some of the art from Greentree hanging in his own living room, Betsey loved art and adored her paintings from Picasso and Toulouse Lautrec, many of which were hung throughout Greentree and her city home.

The Hobbs Family

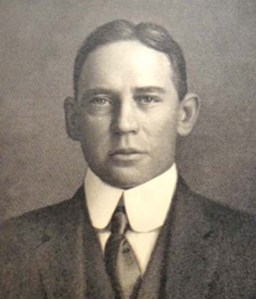

In this tale of two families, the Hobbs family also has an interesting history. Hobbs’ grandfather, Walter Hobbs, came to America from England to work for the Pulitzer family.

“He competed in a cross county race on a bicycle with wooden rims—winning it two years in a row—and used his prize money to come to America,” says Hobbs of his grandfather. “The trophy cup is still in the family.”

After the war, Walter married Erminia Donzelli, who came over from Italy and became a governess to the Pulitzer family. She spoke and wrote in five languages and traveled around the world, taking care of the Pulitzers’ two children, Steve and Ralph.

Soon after, the newlyweds left the Pulitzers to work at the Whitney Estate. Working his way up, Walter became the buildings manager for the estate. Among his many job responsibilities included managing the wine and spirits and petty cash for the entire estate, handling hundreds of thousands of dollars. Walter worked for the Whitneys until he was 88.

“My father grew up on the estate and I worked there a few summers as well,” says Hobbs, adding that the gardens on the grounds on the estate were maintained by a staff of 28 full-time gardeners. “My wife, Cheryl, and I worked on the estate and helped in the greenhouses, including taking care of the prized orchids.”

Hobbs has many fond memories of being on the estate. He recalls his first baseball game as a child, a Mets game where he received a very special gift from the owner, Joan.

“Tom Seaver was pitching and I remember how earthy Joan Payson was; she was a person of the people. As Tom Seaver comes back to the dugout, he pulls his hat down and she shouts profanities at him to play better,” Hobbs recalls. “When the game ended, Joan contacted the manager, Casey Stengel, and said to my grandfather that they had a present for me. They did up a ball that the entire 1965 Mets team signed.”

Hobbs’ home is filled with boxes of history from the past. His father was so passionate about the estate, having grown up and worked on it, that he made detailed notes and wrote down names, dates and anything of importance on the artifacts he came to collect.

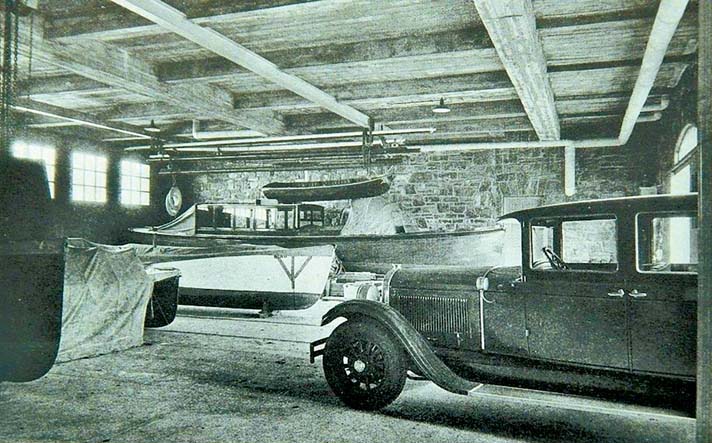

“A lot of what we have was all thrown out. My father and grandfather got it from dumpster diving, all of the personal letters and photos,” says Hobbs, noting that some of the treasures include a pennant that hung on Jock Whitney’s yacht, the Aphrodite; photos of foreign dignitaries and royalty who came to visit; checks signed by Jock; receipts from wine purchases and staff files of every employee of the estate. “I donated a lot to the Long Island Historical Society.”

A Jock of All Trades

Although Jock Whitney’s life was incredible since birth, he acquired his own relationships, many of which revolved around the theater scene as he and Joan invested in many plays, including bringing A Streetcar Named Desire to Broadway. Jock was also lifelong friends with the greatest dancer of all time, Fred Astaire. Keeping in the Hollywood circle, Jock befriended David O. Selznick, the producer of Gone with the Wind.

“Jock knew a literary agent named Kay Brown from the New York theater scene and hired her as the literary agent of Selznick productions. She discovered a manuscript from an unknown author named Margaret Mitchell,” says Hobbs. “When Whitney read the manuscript, he called Selznick, and urged him to buy the story. In 1937, Selznick bought the rights and two year later, Gone with the Wind would become one of the most iconic movies of all time.”

According to Hobbs, when Selznick Pictures ran out of money making Gone with the Wind, Jock put up $850,000 of his own money. Although it was Selznick who discovered Vivien Leigh, it was Whitney who decided to cast her in the role of Scarlett O’Hara. It was also Whitney who made a deal with Warner Bros. to cast Clark Gable, who was under contract with the studio, in the role of Rhett Butler. In exchange for Gable’s service, Warner Bros. distributed Gone with the Wind.

“The stars stayed at Greentree ahead of the premiere in Atlanta and my father caddied for Clark Gable, his wife, Carol Lombard and Vivien Leigh,” says Hobbs.

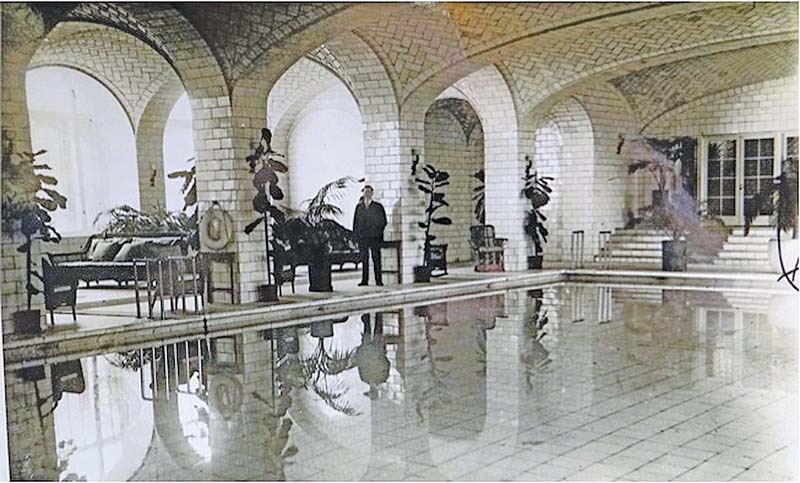

Taking on a more political role, Jock served as the U.S. Ambassador to the United Kingdom during the reign of Queen Elizabeth II. The Queen’s sister, Princess Margaret, visited Greentree and stayed in the pool house in what became known as the Princess Margaret Room.

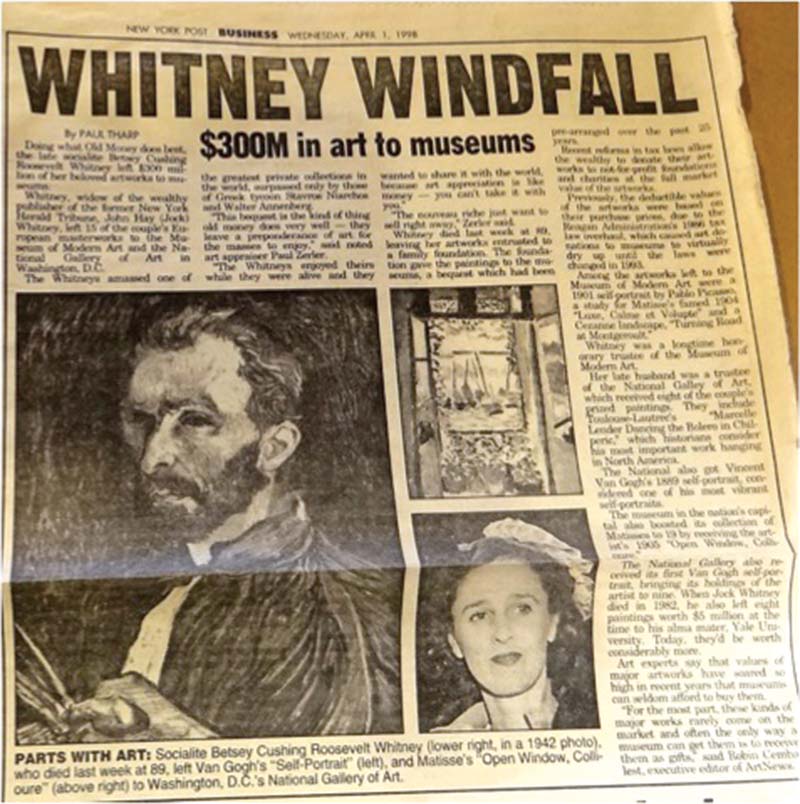

“Jock was the largest private art collector in the country, later becoming the president of the Museum of Modern Art (MOMA). When he died, one of the crown jewels of the art collection, a Renoir painted “Le Moulin de la Galette” (1876) was sold by Betsey for $78 million,” says Hobbs of the painting, which was acquired by Jock in 1929 and hung in the living room of his city home.

When Betsey passed, she left seven major works to MOMA, as she, too, had been a museum trustee for more than 20 years. A Cezanne, Picasso, Van Gogh, Matisse, Bellows, Signac and Cross were all given to the Manhattan museum, while the National Gallery in Washington DC received other works, including Van Gogh’s self-portrait. Six paintings were bequeathed to Yale.

The Greentree Foundation

When the Whitney estate was later divided, land was gifted to several organizations: the North Shore Unitarian Universalist Society (now known as the Unitarian Universalist Congregation at Shelter Rock (UUCSR); North Shore Manhasset Hospital and the Manhasset Lakeville Fire Department. The remaining 408 acres, including the family home, are run by the Greentree Foundation, a philanthropic nonprofit organization, as a conference center dedicated to international justice and human rights issues. The Greentree Foundation was founded in 1982 by Betsey and has owned the property since 2000. Today, Greentree is used by the United Nations. Part of the original garage was converted into gardens and meeting areas for UN use. The stables were also renovated to provide lodging for visiting dignitaries and UN staff.