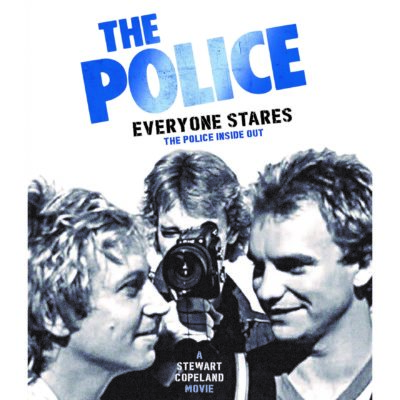

Actor Rob Lowe was once quoted as saying that, “Fame is not a natural condition of human beings.” In viewing the documentary Everyone Stares: The Police Inside Out, that sentiment is readily apparent based on the footage that founding member Stewart Copeland shot from the time he got a Super 8 in 1978 up through the band’s 1982 appearance at the U.S. Festival. While the film originally premiered at the 2006 Sundance Film Festival, the footage had been languishing in storage for decades before film editing breakthroughs allowed the tech-loving drummer to take a crack at assembling the roughly 52 hours of footage into some kind of narrative.

“When I was [playing around with the film], I soon realized that I should not be editing it and I wasn’t quite sure what to do with it, so I put it away and forgot about it. It wasn’t until they invented editing software for folks at home and hard drives with room for lots of memory around 2005 that I was able to go off to the races,” Copeland explained. “I was actually cutting movies of my children playing at the beach and then I realized, ‘I’ve got that rock and roll footage. Lemme see some of that.’ It looked so great that I started making the ultimate home movie. And that was all it was, until I showed it to a buddy who said I should send it to Sundance, and the rest is history.”

While the film part of Everyone Stares kicks off around the time Copeland acquired a Super 8, he used slides to chronicle the early origins of the band when Henry Padovani was the original guitarist before being eventually supplanted by Andy Summers. Throw in Copeland’s sardonic commentary and you have a film that traces the band’s early origins, when it was just Copeland, Summers, Sting and Copeland’s childhood friend-turned-tour manager Kim Turner/traipsing around the United States and Europe, staying in low-rent motels, piling into the car and visiting radio stations and showing up for poorly attended record store appearances. The band’s days of selling out large venues like Shea Stadium were still a few years off. When Copeland made the film back in 2006 (followed by the group’s subsequent 2007 to 2008 reunion tour), he was intrigued by the public’s reaction to it as well as the perspective he got in hindsight.

“When I first made it, The Police was a long-forgotten band from nearly three decades previous. So when it came out to the world, [the film] made kind of a splash. The interest in this movie really did surprise us all. And the interest in the antics, because it starts before we were anywhere. We were still staying in motels and playing crap clubs and doing in-store promotions with nobody there,” he said. “The film is unique in that we got all that early footage. The main thing is that it’s [shot as] a first-person shooter. It’s very personal. As you’re watching, you’re not watching the band over there. The guitarist turns around and talks to you in your face. You’re being shouted at directly by the fans. It’s very much the sensation of being in a rock band, rather than being in a documentary about a rock band.”

While Copeland admits that The Police never saw “…the other side of the parabola—the inevitable descent,” the real-time effects of fame are succinctly captured in the documentary, with everything from the gradual ascent of playing larger venues and the increasing isolation that was a by-product of the band’s fame to fan reactions that ranged from screaming and pleading to the polite reverence the group received from Japanese devotees. In the film, Copeland can be heard rhetorically questioning why they were being put on this pedestal. It’s a perspective that was finely honed during those heady times.

“It really was a rocket ship ride. And I don’t want to be complaining or anything, but there’s a strange anxiety that goes along with it that can best be described as social vertigo,” he recalled. “As a human being, you have a place. You’re part of society—you have people to your left and to your right. But when you get a lot of attention like that, suddenly you’re elevated—more is expected of you. You’re higher up. Your cost of social [screw up] is higher. In a nutshell, no ass scratching in public. You yearn for the days when you were anonymous and you could do that. Adulation becomes obligation. By the way, it’s fair enough—it’s human nature. And really, the rewards outweigh these small prices that we have to pay.”

As for the reaction to the film by his former band mates?

“Sting said he never saw it because he doesn’t watch films of himself. At the time I thought, ‘Uh-huh.’ And Andy loved it because he was all over it as the star of the movie,” Copeland said. “When it played at Sundance, it just happened that Sting was there as well, promoting a film that he produced with his wife Trudie [Styler]. We both screened on the same day and met at a bar afterwards and had a hilarious time. So he was very supportive of the idea of the movie. He is just extremely un-narcissistic these days, which is weird, because we used to tease him all the time back in the day checking himself out in the mirror and he would respond, ‘Dude, we’re rock stars. It’s our job. Matter of fact, you ought to check yourself out in the mirror.’”

Stay tuned for Stewart Copeland’s favorite drummers.