The last thing he wanted was to be recognized. Wearing a fisherman’s cap and rubber boots, the famous writer walked the streets of what he dubbed “a handsome town,” chatting with locals at Cove Deli or relaxing at The Black Buoy bar with his dog Charley. Sag Harbor offered him peace, he told friends and colleagues.

Recently, on August 16, to honor the writer posthumously, officials broke ground on what will become John Steinbeck Waterfront Park. The 1.25 acre property will connect with its iconic windmill and Long Wharf Village Pier through a walkway. The grassy parkland, one of the last remaining waterfront parcels downtown, is open to the public.

The picturesque scene is a far cry from the dust-stripped earth and starving migrant farmworkers whose hardscrabble existence Steinbeck captured in The Grapes of Wrath. His novel earned accolades from peers and readers — selling 10,000 copies per week at one point — but if not for this college dropout’s sharp reporter’s eye, the searing story would have been limited to magazine articles.

SHY BUT SMART

John Ernst Steinbeck Jr. was born in Northern California in 1902. By the time he was 14, the shy but smart kid was locking himself in his room, writing poetry and stories. He wanted to be a writer.

He attended Stanford University for five years but quit in 1925. Moving to New York City, he worked briefly in construction and as a newspaper reporter, but returned to Monterey County to do manual labor while developing his beautiful and simple writing style.

As Steinbeck labored over words and physically exhausting work, the decade-long Great Depression created chaos as more than 1 million Americans fled the dried-up Midwest and Southern Plains, heading to California. But with too many laborers and too little employment, unemployed workers’ ramshackle tent camps proliferated. In 1936, the San Francisco News hired Steinbeck to write “The Harvest Gypsies” series about the corruption-plagued government camps and horrific conditions the migratory families endured. Steinbeck described them as “nomadic, poverty-stricken harvesters driven by hunger and the threat of hunger from crop to crop, from harvest to harvest … The migrants are needed … and they are hated.”

In 1937, documentary photographer Horace Bristol proposed a photo essay to Life magazine about the workers, inviting Steinbeck to visit the camps. Life rejected the pitch saying it was “not important enough,” Bristol told the Los Angeles Times, but Fortune magazine approved.

Steinbeck and Bristol traveled together, documenting the social phenomenon. Bristol remembered Steinbeck as “an extraordinarily sensitive man,” recalling that “the writer’s approach was so soft and good that no one could take offense,” reported the Times.

But the investigative journalist realized the story was too big for a magazine: It should be a novel. That 1939 book revealed the farmworkers’ plight. His years of blue-collar labor enabled him to write what he knew — masterfully — earning him the National Book Award, the Pulitzer Prize for fiction, and the Nobel Prize, and his book was made into an Oscar-winning film. Some of Bristol’s photos were published in Life that year and were used to cast the movie.

On receiving the Nobel Prize, Steinbeck said the writer’s duty was “dredging up to the light our dark and dangerous dreams for the purpose of improvement.”

CHARLEY AND SAG HARBOR

Over the next decade, Steinbeck served as a New York Herald Tribune war correspondent and wrote another best-selling novel, East of Eden. In 1953, he rented a Sag Harbor cottage, and in 1955 bought a small house in Sag Harbor Cove. He loved the village and helped found and co-chaired the Old Whalers’ Festival, now called HarborFest, and helped create the windmill next to Long Wharf.

He spent mornings writing in the property’s shed or on his boat, writing his Newsday column or another novel, The Winter of Our Discontent. He wrote to editor Elizabeth Otis, “I can move out and anchor and have a little table and yellow pad and some pencils … Nothing else can intervene.”

Afternoons were spent fishing or hobnobbing at Sal and Joes or Baron’s Cove resort, or with Truman Capote, Kurt Vonnegut, and other writers at The Black Buoy, his beloved standard poodle in tow.

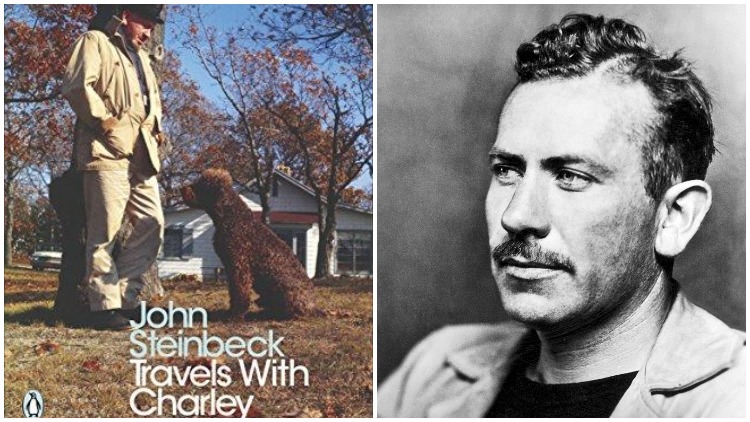

Steinbeck’s legacy includes 31 books, including Tortilla Flat and Of Mice and Men. His last work was Travels with Charley, about seeing America with Charlie after departing from Sag Harbor.

His son Thomas Steinbeck told The New York Times that his father “ had been accused of having lost touch with the rest of the country. Travels With Charley was his attempt to rediscover America.”

John Steinbeck died of heart disease in New York City in 1968.