Elizabeth Gardiner Howell felt chilled, feverish. She was delirious. Hearing unexplained sounds rattling the room, she feared she was losing her senses.

“A witch! A witch!” she shrieked. “Now you are come to torture me because I spoke two or three words against you!”

She swore she saw “a double-tongued woman who pricks me with pins.” Then she coughed up a metal pin.

She insisted that the double-tongued woman was Elizabeth Garlick, who lived down the street — but Garlick was not there. Howell also said, in the language of the 1600s, that there was “an ugly black thinge at ye feete of ye bedd.”

Howell was a married 16 year-old who had recently given birth to a child; she was the daughter of Lion Gardiner, one of the town’s most prominent residents. But the joy of that happy family occasion was shattered when she fell ill.

She cried out, “Oh mother, I am bewitched.” She died the next day, after accusing her poor, quarrelsome neighbor of witchcraft.

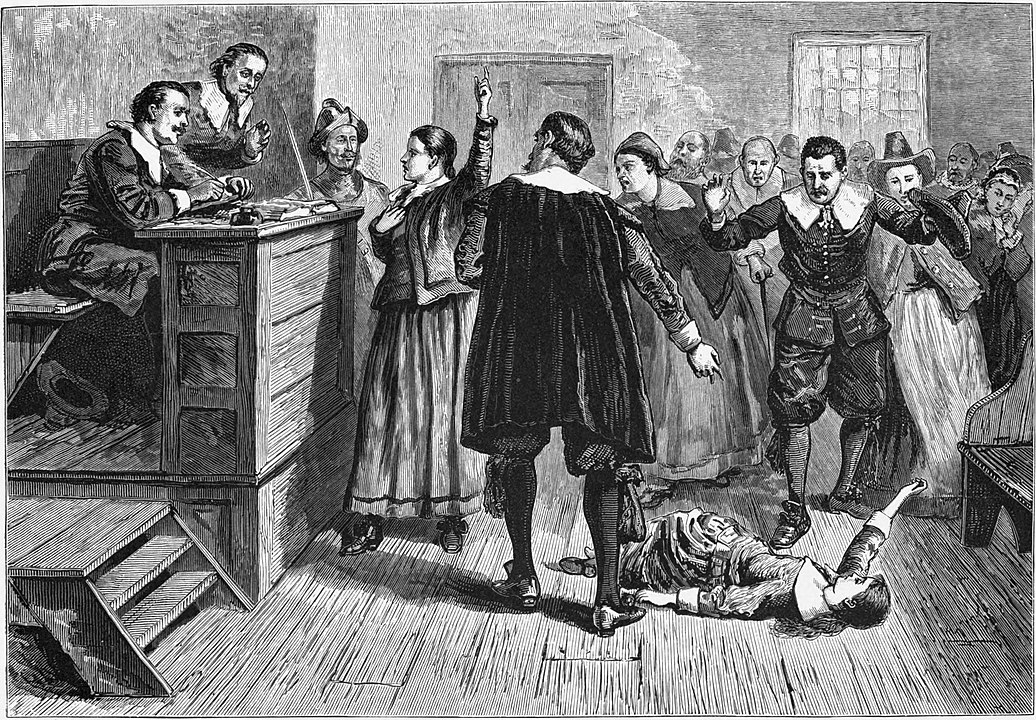

Was this some Halloween performance? Actually, the description is part of an official account of witchcraft in colonial Long Island life. The accusation led to one of the earliest witchcraft trials in the American colonies — and it took place in East Hampton in 1657, 35 years before the notorious Salem witchcraft trials of 1692 and 1693.

VILLAGER WARS

In the isolated English Puritan colony, battles for economic dominance pitted neighbor against neighbor. Accusations flew, paranoia and injustice reigned, and all vestiges of civility unraveled.

The accused, Elizabeth Garlick, was known as “Goody” Garlick (short for “Goodwife;” Goody was a term of address for working-class females). The 50-year-old often quarreled with neighbors who said she was a witch, according to the town records of East Hampton, as it was known then. She was said to cast evil eyes and order animal familiars to do her bidding. She was blamed for the death of a baby she held, and for the disappearances, injuries, and death of livestock.

She was slandered by neighbors, rivals scrabbling to survive in the fishing and farming settlement. To explain the ordeals of Puritan life, before the dawn of scientific thinking, villagers believed in the power of magic, and that the quarreling and distrust were the work of the devil.

Garlick was jailed and tried as a witch by three judges, all men.

INNUENDO, RUMOR, AND RYE

Witch hysteria had gone viral throughout Europe from the 1300s to the 1600s, when tens of thousands of supposed witches were executed. Women who were single, widows, and others on the margins of society were usually the prey in widespread witch-hunts. Accused and declared guilty, they were tortured to confess, burned at the stake, or killed by hanging.

Nearly 80,000 suspected witches were executed in Europe between 1500 and 1660, mostly women said to be lustful and in league with the devil. The highest execution rate was in Germany.

Fueling the fire and brimstone of prejudice was the immensely popular 1486 book Malleus Maleficarum (The Hammer of Witches), written by two inquisitors for the Catholic Church. The guide labeled witchcraft as heresy and dictated how believers could flush out, interrogate, and convict witches.

In the mid-1600s, bias against women continued to flourish, especially among Puritans. They believed that women would yield easily to temptations like desire for things of material value or sexual promiscuity, targeting women who were homeless, poor, or childless.

While many practicing Christians and those of other religions blamed the abnormal behavior of certain women on the devil, there may have been a simpler explanation: diet. The colonists cultivated rye, wheat, and other cereal grasses containing ergot, a fungus. Toxicologists discovered that ingesting foods containing ergot can lead to muscle spasms, vomiting, delusions and hallucinations, according to a 1976 Science report by psychologist Linnda Caporael.

SAVED BY SCIENCE

The Easthampton magistrates referred Garlick’s case to a higher court in Connecticut after Easthampton became part of that colony. The new sheriff, John Winthrop Jr., was a scholar/healer who explained nature’s magical forces as a case of community pathology, not demonic possession. The verdict: not guilty. Garlick was freed and lived to be 100.

Some modern-day researchers conclude that witchcraft accusations are caused by patriarchal institutions seeking to dominate matriarchal ones. The patriarchal attitude can be seen in attacks that target and bully women online more often than men. Some would say that not much has changed, arguing that today’s criminal justice system targets poor, vulnerable, and unruly females, just as it did in colonial times.