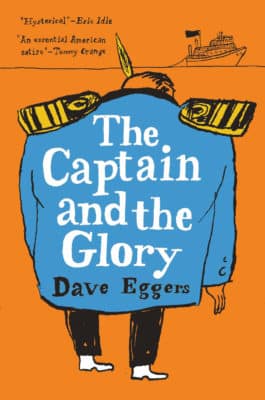

Words reflect real life in The Captain and the Glory

In The Captain and the Glory, Dave Eggers tries his hand at satire. The Captain is President Trump. The Glory is the United States. What went wrong? Eggers can’t believe passengers of such a stately ship would vote for such an individual. The story begins when The Admiral (John McCain) steps down from power. The Captain volunteers to run the ship and enough people go along. Eggers gets his revenge. The Most Foul are the captain’s supporters. Certain People are illegal aliens that The Captain and his supporters both dislike and brutalize. The Kindly Mutineers are the captain’s opponents.

In The Captain and the Glory, Dave Eggers tries his hand at satire. The Captain is President Trump. The Glory is the United States. What went wrong? Eggers can’t believe passengers of such a stately ship would vote for such an individual. The story begins when The Admiral (John McCain) steps down from power. The Captain volunteers to run the ship and enough people go along. Eggers gets his revenge. The Most Foul are the captain’s supporters. Certain People are illegal aliens that The Captain and his supporters both dislike and brutalize. The Kindly Mutineers are the captain’s opponents.

On it goes. Other characters are recognizable. The Pale One is Vladimir Putin. Man So Soft is Kim Jong-un. The Sheriff of the Sea is Robert Mueller and The Strategist is Egger’s fellow Californian, Nancy Pelosi. Eggers is down on The Strategist for not providing a loyal opposition to The Captain. This “entertainment” (as Eggers dubs it) is not for Trump’s supporters. It’s for his opponents who need a good laugh.

Eggers is hopeful. Right off the bat, he describes The Glory as a noble place.

“Among the citizens of the ship there were carpenters and teachers, painters and professors and plumbers, and they had come to the ship from the planet’s every corner,” the author pronounces. “They did not always agree on everything, but they shared a history, and over centuries together they had faced death and birth, glorious sunrises and nights of unease, war and sorrow and triumph and tragedy. Through it all they had developed a sense that they were a mad, ragged quilt of humanity, full of color and contradiction, but unwilling to be torn or separated.” (Apparently, Eggers has forgotten the Civil War.)

Eggers is particularly appalled by the treatment of the Certain People. And so, he ends the novella with the hope that more such people will swim to the ship, replenishing its former greatness. For Eggers, the Trump presidency is a bad dream that he hopes to wake up from.

Eggers is particularly appalled by the treatment of the Certain People. And so, he ends the novella with the hope that more such people will swim to the ship, replenishing its former greatness. For Eggers, the Trump presidency is a bad dream that he hopes to wake up from.

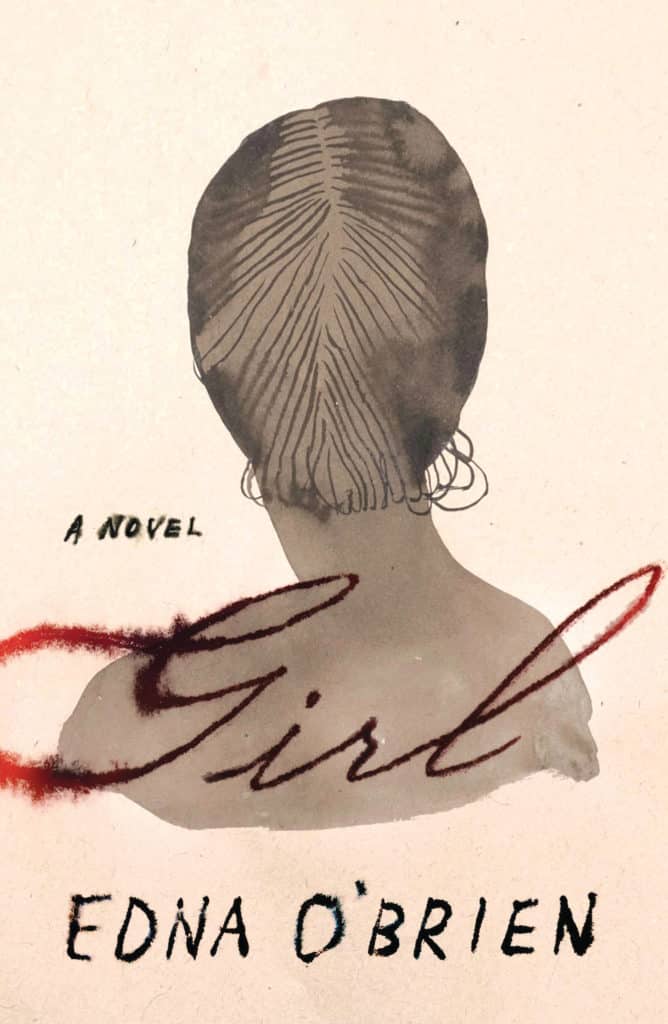

While Eggers indulges in fantasy, Edna O’Brien leaves her usual Irish settings for a novel set in civil war-torn Nigeria. Girl tells the story of a young woman who travels from catastrophe to catastrophe: Abduction, sexual assault, arranged marriage, childbirth (and a husband who skips town), the deaths of both her father and brother to finally, refuge at a convent. The novel is similar to Susan Minot’s Thirty Girls, one set in Uganda’s own civil war. It also carries on a tradition of Western novelists traveling to Africa for fiction: Joseph Conrad, Ernest Hemingway, Saul Bellow and John Updike, among others. O’Brien is closer to Conrad than the lush scenery, adventure and comedy found in other works. The horror, the horror indeed. Girl reminds me of Haile Selassie’s remark that the African continent would never go communist due to the spiritual nature of its peoples. Girl seconds that belief in the saving grace of Christian mercy.