By Gabriella Borter and Kristina Cooke

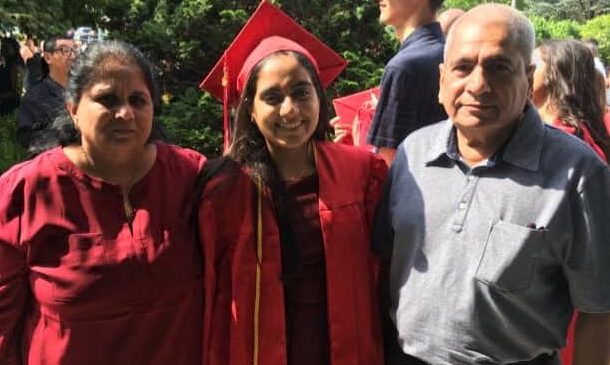

NEW YORK (Reuters) – “Home soon,” Madhvi Aya texted from her hospital bed. “Love you.”

It was the last exchange she had with her only daughter, 18-year-old Minnoli. Three days later, Madhvi Aya died of COVID-19.

Aya, 61, was a physician assistant who had treated patients with the coronavirus. Then she became a patient herself.

She was admitted to the Long Island Jewish Medical Center on March 18 after being infected and died 11 days later. Her family believes she contracted the respiratory illness at her workplace — the emergency room at Woodhull Hospital in Brooklyn.

She told her husband and daughter that she had treated infected patients while wearing only a surgical mask, which offers little protection from airborne infection. Woodhull hospital declined to comment on Aya’s case or whether it had been able to provide its staff with enough protective gear amid widespread shortages nationally.

Aya is among 51 U.S. healthcare workers identified by Reuters as having died after being diagnosed with or showing symptoms of the virus. They include nurses, doctors and technicians who have died in the United States after contracting the disease, according to interviews with hospitals, union representatives and families and a Reuters review of local media reports and obituaries.

There’s no official tally of the deaths among U.S. healthcare workers, and the total could be much higher than the number counted by Reuters.

Minnoli is a freshman at the State University of New York at Buffalo with hopes of becoming a trauma cardiothoracic surgeon. She continued texting her mother for days after her death.

“I kept texting her wanting to believe it wasn’t true,” Minnoli said. “She deserved to live and see me graduate, and become a doctor, and get married and have kids.”

Aya became a physician assistant because she was determined to create a good life for her daughter. The job entailed 12-hour shifts in the emergency room of her Brooklyn hospital.

Since March 1, when the first coronavirus case was confirmed in New York, 28,183 people have tested positive in Brooklyn, and 1,869 people have died, accounting for more than 28% of New York City’s confirmed coronavirus deaths.

RISKING THEIR LIVES

More than 28,440 people in the United States have died from COVID-19 so far.

Of the 51 deaths among healthcare workers identified by Reuters, at least 16 were in New York, one of the hardest-hit states. At least seven were in Michigan, six in Florida, and six in New Jersey.

At least 27 were nurses.

They include Patrick Cain, 52, an intensive care nurse in Flint, Michigan, originally from Canada. When he died, the hospital played “Oh Canada,” the national anthem, over the loudspeakers, according to another nurse at the hospital.

“Everyone knew then,” the nurse said.

His obituary in the Flint Journal describes him as a passionate nurse who always advocated for patients. “He tended to those in need who were exposed to the coronavirus, which eventually took his life,” his obituary reads.

At least 10 of those who died were physicians or resident doctors. Florida doctor Alex Hsu’s daughter Dria described him as calm and reassuring, and said he made others feel heard and important. The 67-year old was the “epitome of self-sacrifice and selflessness,” Dria told Reuters.

“He is our hero,” she said.

Emergency medicine doctor Frank Gabrin, who worked at two New York area hospitals and died from COVID-19 last month, said he believed he contracted the virus while he was forced to reuse the same n-95 mask because of a shortage, according to his best friend Debra Lyons.

“He said it was from having to wear the mask four shifts in a row,” Lyons said in a phone interview. “He got the kit the first night of his first shift, and he used the same kit for all four shifts, 12-hour shifts.”

At least five of the deaths identified by Reuters were hospital technicians, and at least four were EMTs.

The youngest deceased healthcare worker Reuters found was just 20: Valeria Viveros, a nursing assistant in Riverside, California. At least 15 people were in their sixties, and 12 in their fifties.

A KISS BEFORE WORK

If Madhvi Aya was anxious about treating coronavirus patients without the recommended N-95 respirator mask, she never expressed it, said her husband Raj, a retired accountant.

She was an optimist who rarely called in sick or took a day off, Raj told Reuters.

Aya, who immigrated with her husband from India in 1993, awoke at 4 a.m. and would kiss her daughter on the forehead before she left for work.

Shifts in the emergency room were grueling. When Raj picked up his wife from work in the evening, she was usually quiet on the drive home. She would need to close her eyes for 15 minutes before they talked.

“The emergency room is like a war zone,” Raj said. “Even though I was very close to her, she would never discuss it.”

She developed a cough and fever in mid-March. Raj convinced her to call in sick on March 14 and took her to Woodhull Hospital to get a coronavirus test.

At home, she soon needed Raj’s help to get dressed. She was too weak to get out of bed. Her fever persisted.

On March 18, she asked Raj to take her to Long Island Jewish Medical Center, the hospital closest to their home in Floral Park. He waited outside in the car, unable to enter because of the hospital’s no-visitor policy.

She was admitted. She got the coronavirus test result from Woodhull the same day: positive.

Minnoli returned home on March 20 after classes were moved online. She tried calling her mother for a week, but Aya was too weak to answer.

“I’m still praying for you to come home safely to me. I need you Mommy,” Minnoli texted on March 25. “None of us can live without you. I believe in you, please fight back. You’re so strong mommy. I love so much more than you can imagine.”

“Love you,” her mother wrote back. “Mom be back.”

‘MR. AYA, WE ARE SORRY’

Raj called the hospital every day for updates. He learned that Aya was getting intravenous fluids and oxygen. As the days passed, she began having more trouble breathing.

On March 28, the doctor treating Aya raised the possibility of intubation as a final attempt to raise her oxygen levels, Raj said.

In her last texts to Raj on Saturday, she asked her husband to consult her brother, a doctor in India, on whether she should agree to being intubated. Raj read about intubation on the internet, contacted her family and consulted friends.

They told him he needed to say yes, that intubation is a last resort.

The medical team tried to intubate her on Sunday, March 29. But during the process of inserting the breathing tube, doctors discovered blood clots in her lungs, Raj said. They tried to remove them but they were unsuccessful.

“Mr. Aya, we are sorry,” said the person who called from the hospital to tell him his wife had died.

Aya’s death was reported earlier today by The New York Times.

Woodhull Hospital spokeswoman Michelle Hernandez said Aya was one of three hospital staff members who had recently died, but she declined to say if the others had succumbed to COVID-19.

Two weeks after Aya’s death, Minnoli sleeps downstairs in the living room to avoid her mother’s bedroom upstairs. She and Raj have lost the “supermom” who kept the family together, Minnoli said. They have also lost their health insurance and income.

A friend has raised more then $46,000 for Raj and Minnoli through a GoFundMe campaign to cover their expenses. Several of Aya’s coworkers and friends have contributed.

“Madhvi was more than just a colleague to me. She was a great friend and mentor,” one wrote on the campaign page.

“I will always remember you,” said another.

Each night in New York City, neighborhoods around hospitals cheer for healthcare workers to express gratitude for the risks they are taking to save lives. Minnoli watches videos of the applause on social media.

“I can’t help but think, what about the ones who have fallen? What about the ones who are already dead?” Minnoli said. “She was a hero unnoticed.”

(This story refiles to correct the job title “physician assistant”)

(Reporting by Gabriella Borter and Kristina Cooke; Editing by Ross Colvin and Brian Thevenot)

Sign up for Long Island Press’ email newsletters here. Sign up for home delivery of Long Island Press here.