When Diahann Carroll died of complications of breast cancer in October 2019, many mourned for the first African American woman to lead an American TV series. She broke long-standing barriers playing a professional woman and single mother in the award-winning late 1960s TV sitcom Julia.

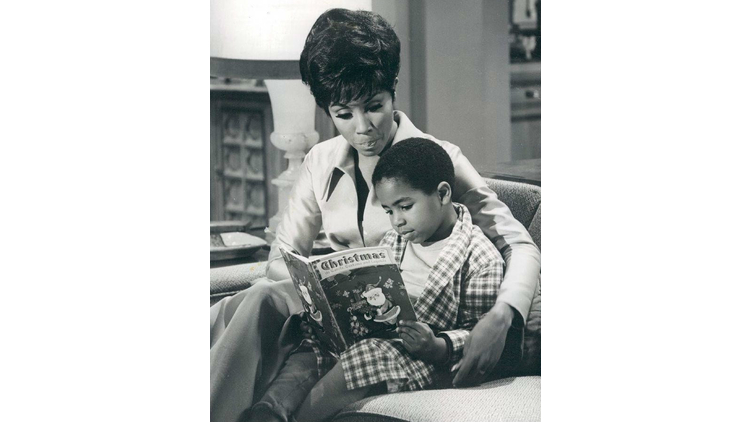

In reality, she was also a single working mother, to her daughter Suzanne. But she augmented that role by becoming a mother figure for actor Mark Copage, who played her TV son. For years, he thought of her as the only mother he had ever known.

Before Julia, Carroll was a singer, Broadway star, and advocate for breast cancer research and treatment. In the summer of 1967, she juggled these roles — plus recording an album and performing nightclub dates — from Fire Island.

PEACE IN THE PINES

Earlier that year, The 31-year-old realized that she hadn’t taken a vacation in 12 years.

She told Newsday, “I’m so uptight, I really need Fire Island.”

She had gone through a divorce from first husband Monte Kay, and sought a place on the Atlantic Ocean for relaxing with her daughter Suzanne, 6. She found it in the Fire Island Pines, the hamlet where Elizabeth Taylor, Rock Hudson, Frank Sinatra, Ava Gardner, Julia Roberts, and other notables could stroll along on the car-less island.

She rented the so-called “ugliest house on Fire Island,” previously rented by movie star Montgomery Clift before his death in 1966. She became the hamlet’s most photographed celebrity, and was praised for her community involvement. She vowed to build a home there, to “have a vacation every year from now on,” adding, “Have you ever seen me so relaxed in the city? Never.”

There, she had time to reflect on life’s challenges and her achievements. She was born Carol Diann Johnson in 1935 in the Bronx, to parents who struggled financially and abandoned her when she was 18 months old. They left her with her aunt in North Carolina for more than a year while they built a better life in New York’s Harlem.

Carroll started singing with a Harlem church choir when she was 6 years old and later attended New York’s High School of Music and Art. By age 19 she was acting in films and on Broadway; five years later the elegant beauty was appearing on Jack Paar’s and Steve Allen’s late-night television shows. In 1962 she won a best actress Tony award for the role created for her by revered composer Richard Rodgers in the musical No Strings.

SHATTERING THE RACIAL CEILING

She personified the new black woman. But her success was an entertainment industry rarity. She described herself as “living proof of the horror of discrimination” in late 1962, testifying before a congressional hearing on racism. “In eight years I’ve had just two Broadway plays and two dramatic television shows.”

The civil rights movement was gaining momentum. While in No Strings, Carroll had received anonymous death threats. The Ku Klux Klan threatened the cast and crew of the 1966 film Hurry Sundown, in which she costarred. The movie was the first to film in the South with an integrated cast and crew, infuriating some locals. They slashed tires. Someone set a cross on fire on the set late at night.

In 1968, Julia aired the first episode of its three-year run on NBC. The premise generated controversy as America was ripped apart by the Vietnam War, riots, and the assassinations of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and presidential candidate Robert F. Kennedy. Julia was condemned for “glossing over the stark realities of life that black Americans faced daily,” wrote The New York Times. But, the paper’s critic Jack Gould added, “At all events the breaking of the color line in TV stardom on a regular weekly basis should be salutary.”

MOTHERING

After her Golden Globe award-winning turn in Julia, Carroll was nominated for an Oscar for the 1974 film Claudine, appeared on TV, and resumed her role as a glamorous chanteuse; three presidents invited her to White House receptions.

She remained close to Mark Copage, who played her television son from age 5 to 8. Because he had no real mother to turn to — his mother left when he was a toddler — he saw Carroll as his real-life mother. Perhaps she became a motherly figure to him because of her own childhood abandonment.

Shortly after Carroll’s 2019 death, Copage wrote in a New York Times piece: “Carroll taught me to always be punctual and a person of my word, as she was …. She would let me know if I started to get a little too pudgy.

”I’ve always wondered if my real mother knew I was on a groundbreaking television show where an actress played the role my real mother didn’t want. For three wonderful years, I was lucky that Diahann did.”

Related Story: Runaway Flu: Could A Century-old Enemy Return?

For more Rear View columns on Long Island history, visit longislandpress.com/category/past-present/rear-view

Sign up for Long Island Press’ email newsletters here. Sign up for home delivery of Long Island Press here. Sign up for discounts by becoming a Long Island Press community partner here.