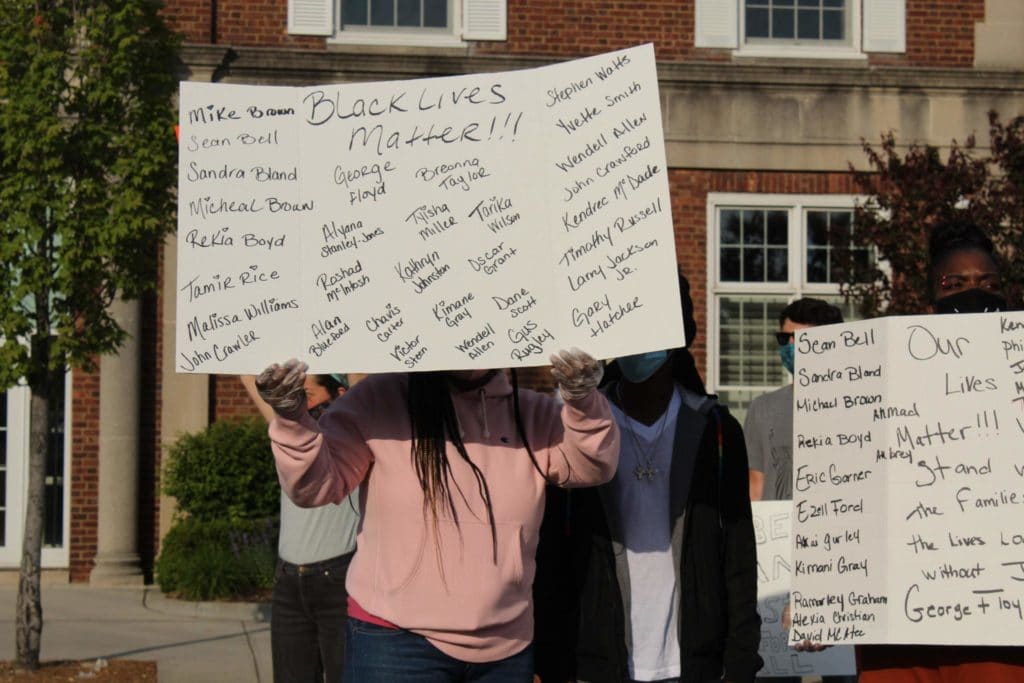

While the protests against police brutality that have been held in Nassau and Suffolk County have so far been peaceful, experts say the issue of racially-motivated police misconduct is far from absent on Long Island.

“There’s a history in Nassau County of mistreatment of persons of color by the police,” Frederick Brewington, a civil rights attorney who has spent decades litigating issues like police brutality on Long Island, said. “Policing in Nassau County, unfortunately, still has not emerged into the real 21st century.”

Those claims of racially biased law enforcement were backed up by a Newsday investigation that found that non-whites on Long Island were arrested at nearly five times the rate of whites between 2005 and 2016.

That discrimination can be reflected within police departments as well. Julius Pearse, president of the African American Museum of Nassau County, became the Village of Freeport’s first African American police officer in 1962. He said he put up with consistent racism from his colleagues as he broke into the force.

“I was not welcome at all,” Pearse said. “They tried every way they could, by using the n-word in front of me, by making black jokes in front of me. We had a probationary period for the first year, I went 13 months taking their abuse.”

Pearse said those legacies exist today, and commented that there was “no way in Hell” George Floyd would be dead if he had been white. He also suggested police can improve their conduct through community policing, but added that the term has become watered down from how he implemented it decades ago.

“When I hear them talking about community policing, it is shameful how they use the term,” Pearse said. “Every church, every social organization, I would sit down and talk with them. There was nothing that went on in that village for a while that I didn’t see before it happened, and I was able to do something about it.”

Brewington criticized several aspects of the police departments themselves, but he also stated the causes of those problems are far deeper. The legacy of redlining and school segregation in communities throughout Long Island, Brewington said, have helped foment implicit biases in the minds of people throughout both counties. Those legacies of discrimination have also created economic disparities that further disadvantage communities of color in the region, and contribute to many of the issues they currently face.

“This is an octopus of a quagmire,” he said. “There’s so many tentacles and it’s so mixed up that we’ve gotten us into a place where we don’t even start to address the rudimentary concerns that show us that African Americans and Hispanics in the pandemic were dying at unprecedented numbers. That’s part of the socio-economic reality that also affects policing and everything else. The police indicators are just a symptom of a very sick set of circumstances that we can make better, but our leaders have to take us there. We can’t be afraid to have that conversation.”

The Nassau County Police Benevolent Association was contacted for this story, but did not respond prior to publication.