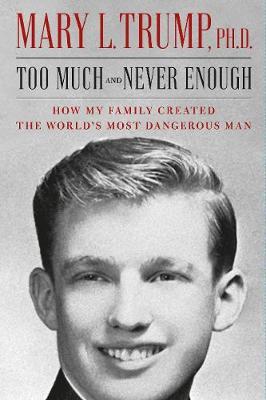

Fred Trump Jr.’s trips to Montauk fueled the family feud that led to his brother President Donald Trump taking over the family business, the president’s niece from Rockville Centre details in her memoir due out on Tuesday.

In Too Much and Never Enough: How My Family Created The World’s Most Dangerous Man, the author, Mary Trump, writes how her late father, Fred Jr., summered at the easternmost tip of the South Fork to escape his father’s cruelty — one of many Long Island mentions in the 240-page book that the Trump family tried to block in court.

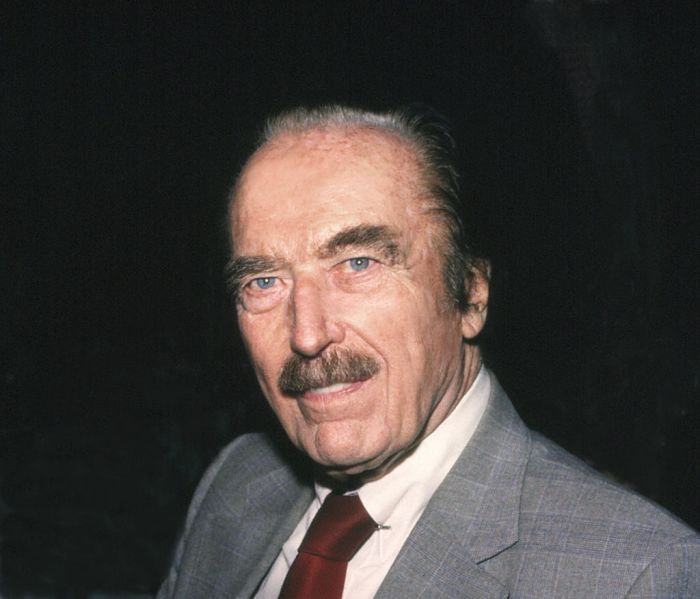

After Freddy, as he was known, died of an alcoholism-induced heart attack at age 42 in 1981, then-teen Mary begged her grandfather to allow the family to scatter her father’s ashes in Montauk. But Fred Trump Sr. instead had her father’s ashes buried, against Freddy’s oft-repeated wishes.

“He wanted to be cremated because he didn’t want to be buried,” Mary writes in the book, recalling how she pleaded with Fred Sr. at her father’s funeral. “Please, let us take his ashes out to Montauk.”

But Montauk only reminded the elder Trump of how his oldest son was more enthusiastic about flying his single-engine plane to the East End to go deep-sea fishing with his friends than taking over the $1 billion New York City real estate empire that Fred Sr. built.

“Montauk,” her grandfather replied, Mary recalls. “That’s not going to happen.”

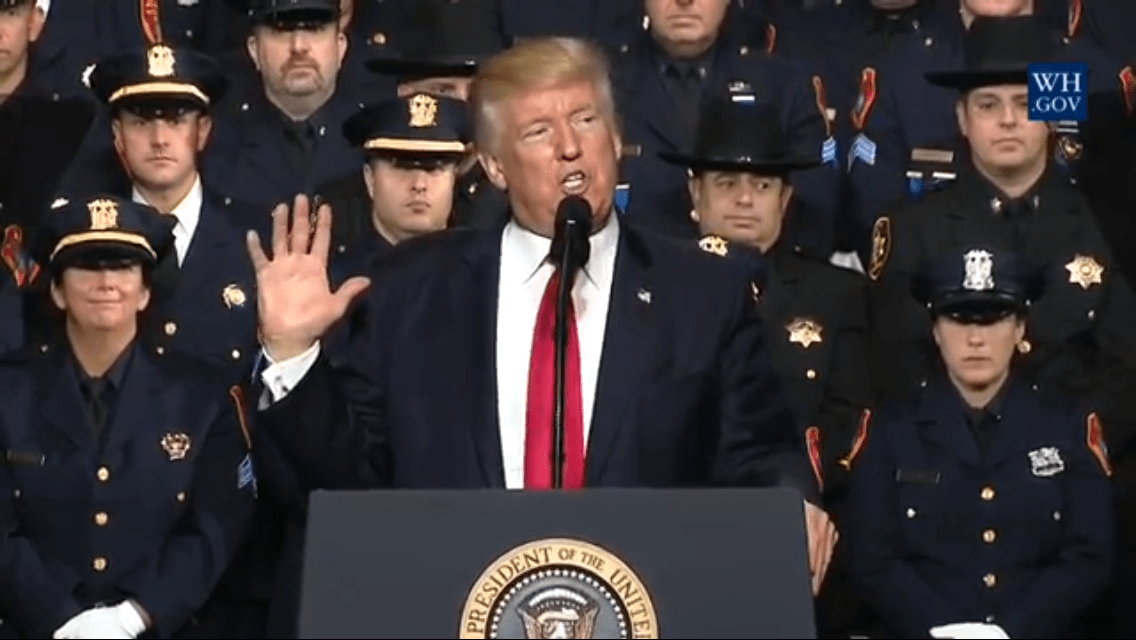

Mary details how Freddy was the original heir apparent to the Trump family business until he was disowned by his father for finding more fulfillment as a commercial airline pilot for TWA at the dawn of the jet age, when pilots were treated like rock stars, than enduring workplace beratement from his father, who built dozens of apartment buildings. But the resentment was building up long before Freddy became a “bus driver in the sky,” as Fred Sr. and Donald called him, Mary writes.

“In the summer, Freddy worked for Fred, as usual, but on weekends he took his friends out east on a boat he’d bought in high school to fish and water ski,” she wrote. Sometimes his mother would have Freddy take his younger brother, Donald, for the trip.

“Sorry guys,” Freddy told his friends, Mary writes, “but I have to bring my pain-in-the-ass little brother along.”

The trips to the East End sparked the long-simmering resentment that boiled over into Fred Sr.’s final act of spite.

“As [Freddy] got older, he became torn between the responsibility that his father placed on him and his natural inclination to live life his own way,” Mary writes. “Fred wasn’t torn at all: His son should be spending time at the Trump Management office on Avenue Z, not with his friends out on Peconic Bay, where he learned to love boating, fishing, and water skiing.”

Before becoming a commercial pilot, Freddy flew a Piper Comanche that he kept at Long Island MacArthur Airport in Ronkonkoma, Mary writes. Freddy flew it between Montauk and Brooklyn.

“My parents rented a cottage in Montauk from Memorial Day through Labor Day so Dad could escape the pressure cooker in Brooklyn,” she writes. “Montauk Airport, really just a small airstrip in an open field, was right across the street from the cottage, making it an easy commute. Freddy’s favorite thing to do was still fly his friends to Montauk and take them out on the water.”

When Freddy had enough of Fred Sr.’s treatment and quit the family business, Donald was tasked with delivering Fred Sr.’s disapproval in person, Mary writes. President Trump told The Washington Post last year that he regretted pressuring his older brother to get into the family real estate business despite Freddy’s reluctance. Donald assumed Freddy’s role Fred Sr.’s heir apparent.

Freddy eventually did return to working with his father, but was blamed for the company’s failure to get approvals to redevelop the former Steeplechase amusement park property in Brooklyn.

“Maybe you could have kept your head in the game if you didn’t fly out to Montauk every weekend,” Donald told Freddy in front of Fred. Sr., Mary writes, adding that their father ordered Freddy on the spot: “Get rid of it.”

Fred Sr. held a grudge, she writes. At one point, Freddy and his wife tried to buy a four-bedroom house in Brookville, but the mortgage application was rejected, despite his family’s wealth.

“The most plausible explanation was that Fred, still burned by what he considered his son’s betrayal and reeling from the failure at Steeplechase, had intervened in some way to prevent the transaction,” Mary writes.

After Fred Sr. died, Mary and her brother Fred learned that they were largely cut out of their grandfather’s will. When they sued, the family cut off their medical insurance, despite Fred’s wife having recently given birth to their third child, William, who was diagnosed with cerebral palsy and required expensive treatments.

Mary and her brother hired Jack Baronsky, a partner at the high-powered law firm of Farrell Fritz in Uniondale, to handle the case. Years later, after the case was settled and her uncle was elected president, Susanne Craig of The New York Times knocked on her door.

“Her khakis, button-down shirt, and messenger bag placed her out of Rockville Centre,” Mary writes. She was right. Craig’s from Manhattan.

Despite insisting that she couldn’t talk to the press, Craig eventually convinced Mary to go back to Farrell Fritz, collect Fred Sr.’s tax records that were part of the lawsuit, and turn them over to Craig and her colleagues in the parking lot of the RXR Plaza building on Hempstead Turnpike. The Times used the documents to expose the president’s role in an allegedly fraudulent tax scheme — which involved several properties on LI — detailed in the newspaper’s Pulitzer Prize-winning investigation. Among the revelations were the Trump family setting up a shell corporation called All County Building Supply & Maintenance, with an address in Manhasset, that was allegedly used to launder money to avoid taxes.

Mary, a clinical psychologist, spends much of the book analyzing the deep-seated motivations behind Freddy and Donald’s insatiable desire for their father’s approval between making shocking revelations about Donald hiring a friend to take his college entrance exam and making awkward remarks about her breasts. But the story is interwoven with local references, such as how to mingle with politically connected people to get developments built, Donald joined country clubs on LI.

“He joined an exclusive beach club on the South Shore of Long Island and later North hills Country Club, both of which he considered excellent places to entertain, impress, and rub elbows with men best positioned to funnel government funds his way, much as Donald would do at Le Club in New York in the 1970s and at golf clubs everywhere,” she wrote.

Some things, it seems, never change.

Related Story: Publisher Moves Up Release Date For Tell-All By Trump’s Niece From Long Island

Related Story: Trump’s Niece From Long Island Set To Publish Tell-All

Sign up for Long Island Press’ email newsletters here. Sign up for home delivery of Long Island Press here. Sign up for discounts by becoming a Long Island Press community partner here.