As racial justice protests continue across Long Island, police and lawmakers are debating how best to address the issue of police brutality without handcuffing officers’ ability to effectively protect communities they serve.

There have been more than 100 protests against police brutality on LI since a Minneapolis police officer allegedly murdered George Floyd in May, triggering nationwide demonstrations that have been dubbed the largest-scale civil rights movement in American history. New York State, Nassau and Suffolk counties and some villages have all proposed, and in some cases enacted, police reforms in response — prompting some soul searching along the way.

“As someone that has always been law-abiding … I’ve been called ‘boy,’ I’ve had guns drawn, I’ve had a gun held up to me, and it’s from law enforcement,” said Suffolk County Legislator Dr. William Spencer (D-Centerport), one of two Black members of the county legislature. “So when I get pulled over, even in Suffolk County, until the point where that officer recognizes who I am, I’m terrified.”

The national reckoning on race relations has prompted nationwide calls to defund police departments and reallocate the taxpayer money to social services programs as was enacted in New York City, but local leaders have resisted the idea.

Some measures have been more symbolic, such as the Village of Hempstead, the municipality with the highest density of Black residents on the Island, renaming its Main Street “Black Lives Matter Way.”

STATEWIDE REFORMS

New York State lawmakers passed police reforms in June. Gov. Andrew Cuomo signed into law a 10-bill legislative package that included a ban on police using chokeholds, mandated that New York State Police wear body cameras, and designating as hate crimes false accusations made to 911 based on religion, race, or other identifiers.

Most notable was the repeal of a 1976 law that allowed police departments to shield disciplinary records from public scrutiny. For years, critics of the law had called for greater transparency, while backers said the law protected the privacy of essential workers.

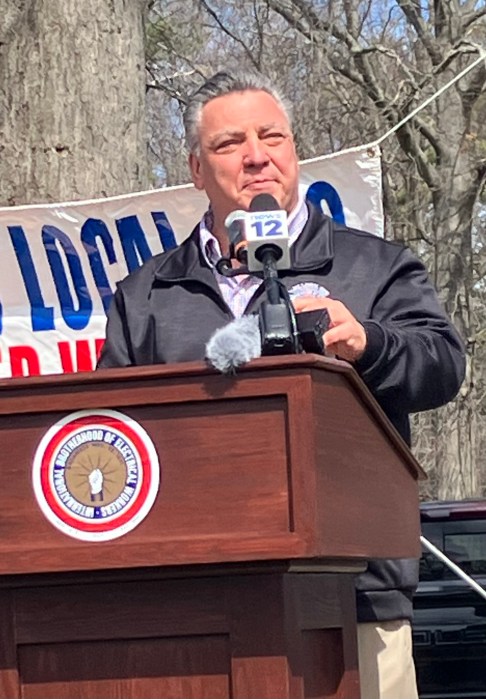

“They are passing legislation that is actively hurtful and detrimental to law enforcement officers and their careers,” Suffolk Police Benevolent Association President Noel DiGerolamo, who represents rank-and-file police officers, said in a radio interview.

Cuomo also created the New York State Police Reform and Reinvention Collaborative in which 500 police departments statewide are mandated to reform with community input by April or risk losing state funding.

“We’re not going to be as a state government subsidizing improper police tactics,” Cuomo said.

Local officials expressed confidence in county training programs.

“I believe our academy is world class,” Suffolk County Police Commissioner Geraldine Hart said, touting the department’s language assistance and hate crime training.

Nassau County Executive Laura Curran took it a step further and mandated anti-bias training for all county employees, not just members of law enforcement.

Both the Nassau and Suffolk police have been under consent decrees requiring the U.S. Department of Justice monitor their hiring practices to avoid discrimination since the 1980s. Suffolk police also remains subject to DOJ review of its relations with the Hispanic community as part of a 2014 discrimination lawsuit settlement.

POLICE PUSHBACK

As the marches and police reforms advance, several pro-police Back The Blue rallies have been formed in response.

The Nassau County Legislature launched a Blue Ribbon Initiative, encouraging residents to show support for police officers by displaying a blue ribbon outside their home or business. And lawmakers expressed concern for officers’ health and safety while juggling marches and pandemic rules enforcement on top of daily duties.

“This notion of defunding the police, that somehow we don’t need police, it just doesn’t work,” Suffolk County Executive Steve Bellone said.

“When you speak to defunding the police, you’re eliminating core services, which is going to affect minority communities the most,” DiGerolamo said, noting that the majority of 911 calls come from minority communities.

REBUILDING TRUST

Officials recognize the need for improving relations between police and the communities.

“Current events have demonstrated that people from all racial and ethnic backgrounds are frustrated with law enforcement, and they have some legitimate reasons to feel this way,” Suffolk County Sheriff Errol Toulon, Jr. said while announcing the formation of an advisory board to provide community input on local policing efforts.

“We have to change the culture in policing,” Hart said. “Making sure that every police officer is involved with the community… that has to be in the DNA of our department.”

In Nassau, Curran announced the creation of the Police and Community Trust committee that will join community activists with police officials for discussions on how to improve Nassau’s community policing model.

“As a young Black woman from this community I’m excited to have and push these conversations forward,” said Blair Baker, one of four community activists represented on PACT.

Advocates are still pushing for Nassau and Suffolk counterparts to New York City’s Civilian Complaint Review Board, a program instituted in 1993 that allows citizens to file complaints to a third party investigator rather than police departments. Another Nassau bill seeks to create an alternative reporting option for community members to reach a specialized mental health crisis response unit without calling 911.

“How is it humanly possible that an officer who starts in the academy at about the age of 24-26 can be all that in every [emergency] situation?” retired 25-year NYPD officer Dennis Jones asked at a Long Island Advocates for Police Accountability rally.

“Our police officers are people too, and our system, the way it is currently structured, does not provide them the monitoring and the support that they need to be able to properly do their jobs in their communities,” said Rashmia Zatar, executive director of STRONG Youth, a Uniondale-based anti-gang violence nonprofit.

She pointed to heightened substance abuse, domestic abuse, and suicide rates among police officers that have ripple effects on law enforcement’s abuses in community responses.

BODY CAMERAS

Nassau and Suffolk lawmakers are also searching for vendors in anticipation of expanding police body-worn camera systems on Long Island. Suffolk previously experimented with a pilot program in 2017, while a $150,000 pilot in Nassau stalled in 2015 after objections from police unions.

Now, legislators are pushing to bring these programs to full deployment. Nassau Legislators Siela Bynoe (D-Westbury) and Carrié Solages (D-Elmont), who were behind the 2014 effort, renewed their calls for a countywide bodycamera program.

“Suffolk County, New York State, and the entire nation are entering a new phase of understanding and advocacy with respect to the use of force by police and ensuring accurate monitoring of police activity,” Suffolk County Legislator Jason Richberg (D-West Babylon) wrote in a recent resolution.

Body cams not only provide a record in case of police misconduct, but may also protect officers from being falsely accused, according to local police chiefs. While an important tool for maintaining objective records, clear protocols regarding when officers must turn the cameras on and when they are allowed to turn them off, are needed, lawmakers said.

As legislators are mulling how to pay for an expensive new program amid a pandemic-induced budget crisis, some local villages are taking matters into their own hands. The Village of Head of Harbor announced June 18 they would equip all officers with body cams. In 2015, the Village of Freeport was the first municipality in New York State to equip all 95 officers with body cameras.

Ironically, a recent high profile police brutality case occurred in Freeport. A viral video from December shows 44-year-old Freeport resident Akbar Rogers screaming for help while being physically assaulted by police officers, one of whom is the mayor’s son.

“But for the grace of God, this rally could have been my memorial service,” Rogers said at a rally June 29. “But for the grace of God, I could have ended up like George Floyd.”

Charges against Rogers for assaulting a police officer were dropped July 7. He has since filed a $25 million suit against the police department.

NEXT STEPS

Some advocates say the police reforms don’t address the underlying systemic racism on LI, such as the continuing practice of redlining — real estate agents steering minorities away from buying homes in predominantly white communities, exacerbating the region’s status as one of the most segregated suburbs in the nation.

Last month, Nassau Legislators Solages and Arnold Drucker (D-Plainview) proposed creating a database of racially restrictive covenants in housing policies, with the goal of educating the public on structural racism. Both Suffolk and Nassau legislatures also recently passed addendums to local human rights codes protecting natural hairstyles, protective hairstyles, and religious garments from discrimination.

“It’s important in this day and age, especially with the diversity of our county, that we recognize that these hairstyles and garments are important to people’s different cultures and faiths and they should be able to have those things without worrying about discrimination in terms of employment or housing,” said Nassau Legislature Presiding Officer Richard Nicolello (R-New Hyde Park).

Advocates remain cautiously optimistic that real progress will be made.

“Governments at every level need to address the structural racism that underpins police brutality,” said Elaine Gross, president of E.R.A.S.E. Racism, a nonprofit that investigates housing discrimination. “Only then will the African American community be treated fairly by the police.”

Sign up for Long Island Press’ email newsletters here. Sign up for home delivery of Long Island Press here. Sign up for discounts by becoming a Long Island Press community partner here.