By Shaireen Rasheed

I had two quarantined graduates this year celebrating their perspective high school and college class of 2020. And as a way to celebrate their graduation my newly minted graduates wanted to exercise their first amendment right and participate in the local and national Black Lives Matter (BLM) marches. This was their civil rights moment, their revolution and it was not my place to tell my young, independent thinking justice activists what to do in the face of a global pandemic. All masked up my husband and I joined our off springs at the marches and walked with them as they marched across the Brooklyn Bridge in solidarity with their peers and those who had lost their lives, as victims of racial oppression and police brutality. The energy at the marches was palpable and the urgency of their message was felt far and wide. Even at my local town march on Long Island organized by the BIPOC (black, Indigenous and people of color) youth from the area, hearing the young courageous activists share their experiences of racism in their daily lives was painful to hear. It was their truth and I felt privileged and humbled to bear witness to it as they recounted candid stories of racist encounters in their classes, in the playground, amongst their friends as they navigated their black and brown bodies in spaces that didn’t include them. As I looked around the crowded town dock it was promising to see that the urgency of the BLM message was reflected across all colors, ethnicities, sexualities, races and religions. Every pensive Generation Z was kneeling for almost 9 minutes in solidarity with George Floyd who was killed by a police officer who put his knee on Floyd’s neck for at least 9 minutes. A young teen was holding a sign with the face of Tamir Rice, the 12-year-old Black child was shot to death by a police officer in November 2014 while playing with a toy gun at a park in Cleveland. As a mother of a teen boy Tamir Rice’s image brought up a lot of emotions for me. Tamir Rice was my son’s age and would be celebrating his 18th birthday graduating with my son if he was alive today. Or Trayvon Martin the 12 year old teen who was shot in 2012 in Florida teen for wearing a hoodie, would be graduating college with my daughter had he been alive. Through my tears I found my shaking voice synchronizing itself in unison with the other young voices in town as we all chanted, “Say their names.’’ And there were so many names. So many needless deaths, so many unmet possibilities of lives cut short as a result of police brutality and institutional and systemic racism.

We as parents, allies and educators can no longer afford to sit back and become complacent in the face of these increasing glaring inequalities. If there is anything I have learnt in hearing the pleas of the young, brilliant black and BIPOC Black Lives Matter activists during the marches, it is that being an ally involves so much more than paying lip service to the movement or shallow performative gestures. The only way we can truly support the BLM movement is to support our activists by giving them the space to articulate their own oppressive obstacles and create through their own actions places of transformative change. To paraphrase Ibram X Kendi it is not enough for us to commit to not be racists, we have to actively be anti-racists.

An anti-racist pedagogy within this context goes beyond the Brazilian philosopher and educator Paulo Freire’s “banking education” in which students are passive recipients of know- ledge transfer from teacher to student. To quote the educator and critical theorist Henry Giroux (1993):

Administrators and teachers need a new language capable of asking bold questions and generating more critical spaces open to the process of negotiation, translation and experimentation . At the very least educators need language that is interdisciplinary, moving skillfully among theory, practice and politics . This is a language that makes the issue of power and ethics primary to understanding how schools construct knowledge, identities, and ways of life that promote nurturing and empowering relations . Students need to learn that the relationship between knowledge and power can be emancipatory; that their histories and experiences matter, and that what they say and do can count as part of a wider struggle to change the world around them. (Giroux, 1993, pp. 24-25)

It involves that as a district and a community we intentionally commit to systemic changes in our schools that includes hiring more teachers, counselors and administrators of color in keeping with the changing student demographics. Ninety-two percent of Long Island public-school teachers are white. In nearly two-thirds of Long Island schools, there are no black teachers. In more than two-fifths of them, there are no Latino teachers. And most children grow up in segregated communities that divide along school district lines.

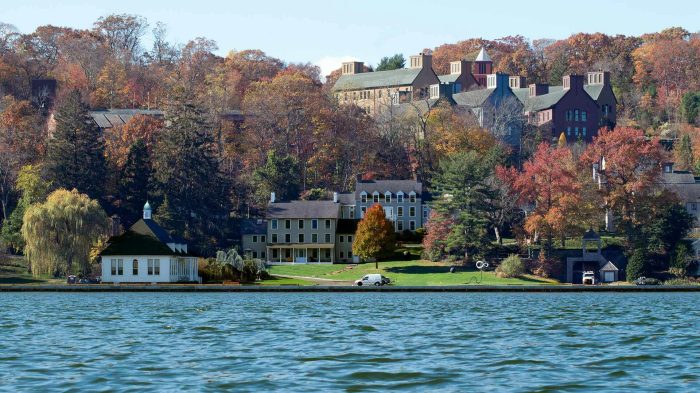

Those were the findings discussed at the Long Island Educator Diversity Convening at Hofstra University last spring. Long Island is historically the most segregated school district in the country. As Elaine Gross, the founder of Erase Racism wrote, ‘’ Today, Long Island is one of the 10 most racially segregated metro regions in the nation. Its two counties have 125 school districts that mirror the residential segregation — a design that ensures segregated and unequally resourced schools — and segregation is on the rise.”( https://thehill.com/opinion/civil-rights/500869-underlying-americas-unrest-is-structural-racism) According to ERASE Racism, (an organization committed to advancing racial equity in Long Island) in 2017, dramatically more black and Latinx students on Long Island attended segregated schools than 12 years earlier. Statewide, New York has the most segregated schools in the nation. And even when positive change has been embraced in educational spaces on the Island, it has been very slow in keeping with the changing demographics of the population that it continues to serves.

It is not a coincidence that our remedial classes have more ENL (English as a New Language) students and students of color. On the flip side the makeup of the majority of the honors and gifted programs in districts across Long Island consist of a homogeneously white student body. Our Board of Education members rarely reflect the diversity of our parent populations and the demographics of the majority of our teachers , administrators and counselors doesn’t reflect the students they serve. Not that there is a shortage of excellent candidates to choose from because as a professor of education I can attest to the talented novice and seasoned applicant pool of teachers of color our universities produce every year. For those lucky POC (person of color) educators and administrators who do get their foot in the door in the Long Island schools, many unfortunately leave. As a lot of teachers of color coming from urban schools, in the absence of institutional support find it challenging to navigate the suburban culture of their Long Island schools.

In this era of global and cultural pluralism we cannot simply unlearn racism and celebrate diversity, when the cultures in which learning takes place are shaped by textbooks, curriculum and teachers that are part of the dominant narrative or simply put-not diverse nor reflect diverse viewpoints. This status que hinders the facilitation of civic minded students who become critical thinkers and advocates of change in and out of their classrooms. Which is why it is incumbent on every Long Island district to intentionally commit to putting policies in place to recruit, retain and tenure diverse teachers, counselors, psychologists, social workers and administrators. Only then will black and brown lives matter in the classrooms.

Shaireen Rasheed is a professor of Philosophy, Multiculturalism and Social Justice at Long Island University. She is also the director of the doctoral program in Interdisciplinary in Education and is also a diversity/equity/inclusion consultant that works with educators to create inclusive pedagogies for diverse students, particularly exploring best practices to create anti-racist pedagogies in K-12 and institutions of higher learning. She currently serves on the Port Washington District’s Diversity Taskforce.