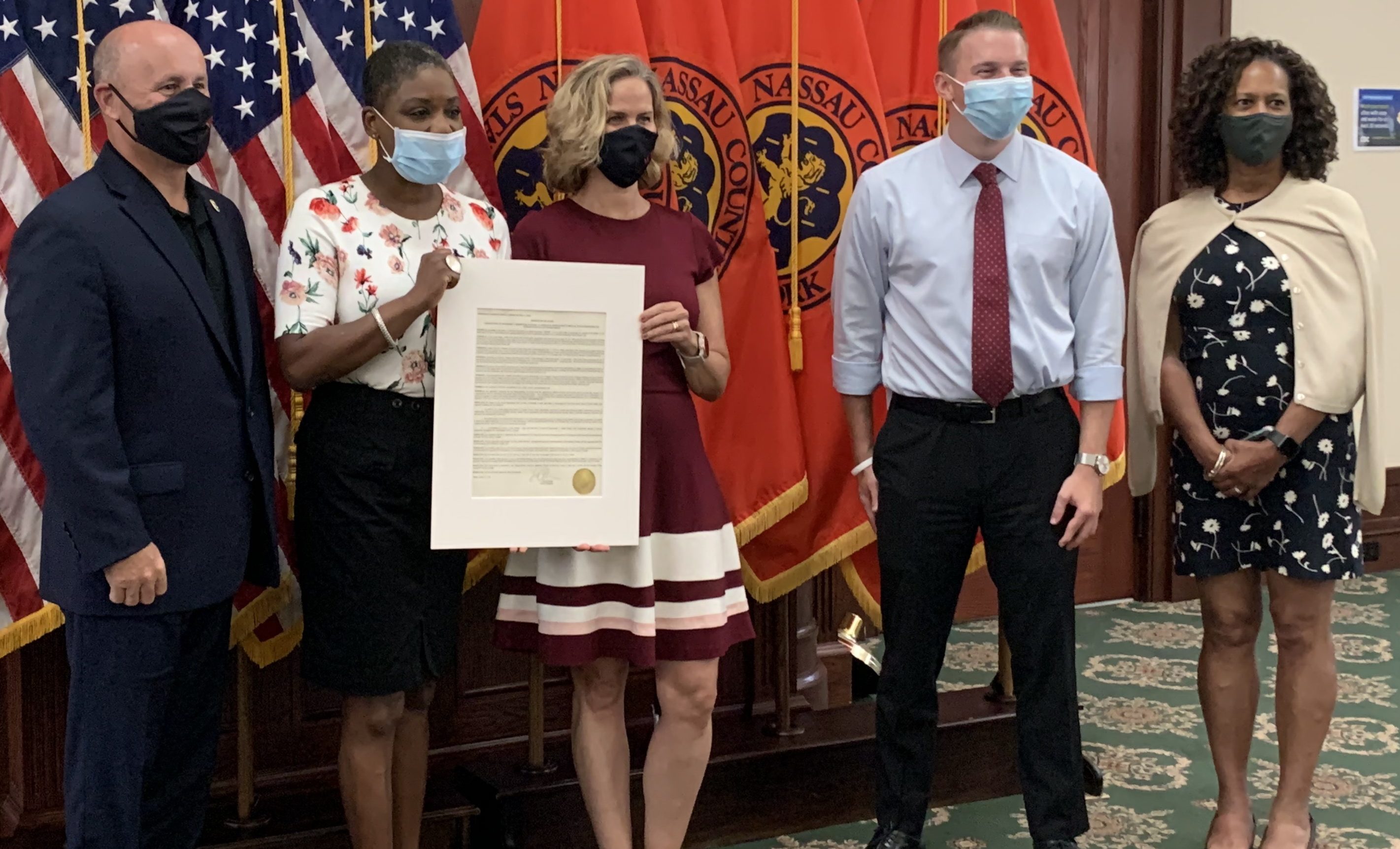

Nassau County Executive Laura Curran signed a bill Wednesday that addresses growing calls for reform around the response by law enforcement to mental health crises.

The bill, which was introduced by Legislators Siela Bynoe (D-Westbury) and Josh Lafazan (I-Syosset) in late June and passed unanimously by the county legislature in early August, calls for the creation of a committee that will study alternative approaches to law enforcement intervention in situations regarding mental health. Curran called the bill “another positive step” towards building trust between county residents and police officers on an important issue.

“Mental health response is one of the toughest parts of the police’s job, and increasingly it’s becoming a bigger part of the job,” Curran said. “We ask a lot of our police these days and we owe it to them to make sure they have the training, the tools and the support they need to do their jobs.”

Curran also cited increases in the number of community affairs police officers and the recent push for mandatory body cameras on county officers as other steps her administration has taken to strengthen police-community relations. But the bill signed ultimately marks one of the legislature’s first concrete responses to an issue raised by the nationwide protests around racial injustice that have also played out nationwide and across Long Island since late May.

The committee, which will be co-chaired by Nassau County Police Commissioner Patrick Ryder and Nassau County Department of Human Services Commissioner Dr. Carolyn McCummings, will likely seek to redirect the responsibility of mental health responses by law enforcement in one of two ways, according to the text of the bill.

The first would see the creation of a mental health unit within the police department staffed by mental and behavioral health professionals, which would aid law enforcement in providing resources and assistance to members of the mental health community. The second would see an expanded role for mental health professionals, like those in the Nassau County Mobile Crisis Team, by “co-deploying” them with police officers in response to all mental health related calls.

In its current state, the county’s mobile crisis team, which is run by the Department of Human Services, has its own hotline to respond to mental health calls by dispatching social workers and nurses to the scene of a crisis. But when a 911 call is placed reporting a mental health crisis in the county, the decision to alert the mobile crisis team often rests with the responding police officers and the police department’s emergency services personnel, according to statements by a police official at the legislature’s August 3 session.

Left without a coordinated response to these situations, McCummings told the legislature that the police often do not call the crisis team for help, something the new committee could help resolve.

“The resolution would be a good way for us to establish a protocol for having both the mobile crisis team and the police department work together in order to make sure that any of these calls are handled properly,” McCummings said.

At the bill signing, Bynoe said the committee presents a chance for the county to “fine tune” its approach towards aiding the mental health community while reducing the possibility for escalations with law enforcement.

“We look at how we respond to physical aided calls when they come into 911 — we dispatch police and we dispatch EMS,” Bynoe said. “I think that it’s important that when we get a call that comes in from some loved one, a relative, a friend or a bystander who notices somebody in crisis, that we send the proper personnel to support our police or that our police receive higher training in the area of mental health so that they can respond in the best possible way.”

Not immune to issues surrounding law enforcement response mental health crises, Bynoe cited several recent incidents on Long Island that inspired the legislation, including the death of a man with a history of mental illness who was shot by two Nassau police officers in Oceanside last September after he charged at them with a sword. An internal investigation by the department’s homicide squad into the shooting later ruled that it was “justified.”

Officers in the county currently receive around 40 hours of training in areas including communicating with those in emotional distress and de-escalation, with emergency services unit officers receiving an extra five-day course on dealing with mental health crises. In both 2018 and 2019, the department responded to more than 300 violent mental health calls, according to statistics shared at the August 3 session.

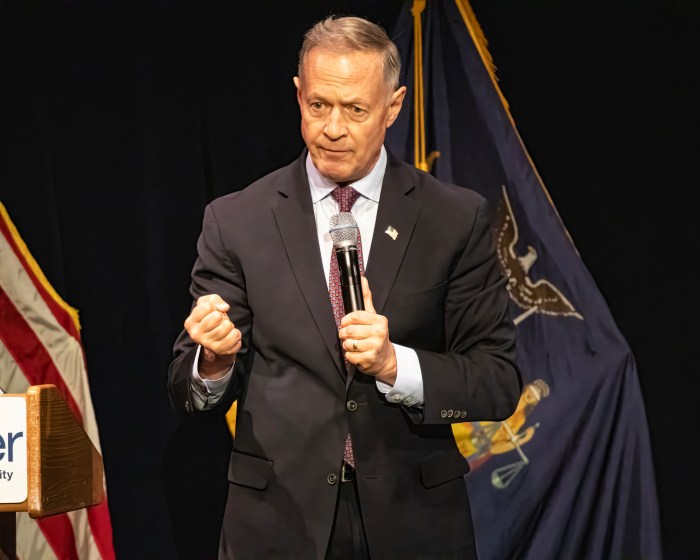

Also speaking at the bill signing, Lafazan noted that mental health related calls have risen considerably in the last few decades, while nationally, police departments only dedicate a fraction of their cadet training time towards responding to those crises. Lafazan added that while the Island-wide protests certainly pushed the full legislature towards action, the decision to call for a committee was not reactionary and instead rooted in better serving the community.

The committee, which will also consist of two non-voting members in addition to Ryder and McCummings, will now have 30 days to hold its first meeting and six months to submit its report and recommendations to Curran and the legislature.

Sign up for Long Island Press’ email newsletters here. Sign up for home delivery of Long Island Press here. Sign up for discounts by becoming a Long Island Press community partner here.