I’ve written candidly in this space about living with a blood cancer, Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma, since 2010.

According to the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society, almost 180,000 people in the United States were expected to be diagnosed with leukemia, lymphoma or myeloma by year’s end, about one every three minutes.

Last time I checked in, I revealed that I had undergone a stem cell transplant in December 2019. Just to refresh—the aim was to replace my immune system with a new one and activate the donor’s stem cells to more effectively seek and destroy my cancer cells.

Naturally, as with any medical procedure, one can review the odds that suggest how often or well a procedure works and for how long, depending on certain variables.

I didn’t dwell on the odds though. I thought a transplant was the best available option, as the time in between relapses was shrinking after each new round of chemotherapy and immunotherapy.

Despite my downplaying the percentages, one thing that I was advised that did stick with me was that with transplant comes the risk of developing something new that could be just as challenging as cancer to treat. It is potentially life-threatening condition called Graft versus Host Disease (GvHD).

What is GvHD? It is a condition that can develop when the donated stem cells (the graft) see the healthy tissues in the patient’s body (the host) as foreign and attack them along with the cancer cells they were intended to kill.

I was prescribed certain drugs before and after transplant to mitigate the risk of GvHD. One is an immunosuppressant which aims to slow down the immune system by preventing the new white blood cells from going into full attack mode.

Over time, the immunosuppressant dosage was incrementally reduced to open the door a little wider for more protective donor cells to pass through and circulate.

I was doing fairly well until I started to experience some new symptoms, the most obvious of which was an itchy rash and skin blistering, which are consistent with GvHD. To address this, my immunosuppressant intake was increased to slow down the release of new white blood cells. In recovery, calibration is key.

Although I can conceal it quite well with my stoic bearing, I was freaking out imagining I would soon have to cope with a new chronic disease as the result of aggressively treating the other one. It is still a little early to know where I stand as the symptoms have begun to dissipate with the adjustment of my meds. The upside is that I know the new cells are working, if not yet as precisely as I had hoped they would.

Why am I sharing all this? Maybe you or a loved one is coping with a chronic disease too—not necessarily cancer, and can relate.

Although I offer a living example of someone living with a chronic disease, who is functioning at a fairly high level with the benefit of excellent medical care, loving family support, generally good fitness, a positive attitude, a realistic outlook and (maybe) a little luck, it has not been easy to accept the gradual deterioration my health in real time.

I am grateful for each day and, at the same time ever-vigilant for the next sign or symptom—rash, cough, gastrointestinal glitch, swollen lymph node, joint pain, errant blood count or whatever it is that signals my vulnerability and another physical and emotional challenge ahead.

Throughout my life, I have always held on to a sense of hope that I might transcend whatever it was that I was facing, as well as a feeling of gratitude for each step forward. Nevertheless, it would be disingenuous of me not to confide in you that managing doubt and disappointment is always a part of my experience, as well.

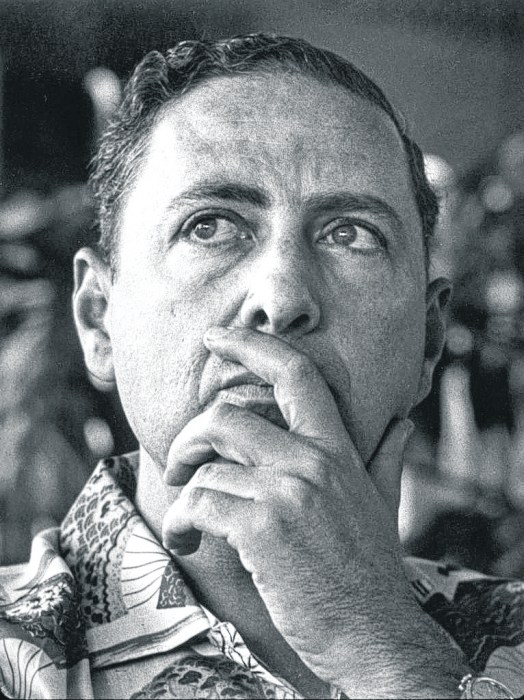

Andrew Malekoff is a New York State licensed social worker and an Anton columnist.