Long Island is known for its charming villages, historic structures, picturesque harbors, and popular festivals. But buried in the past, behind the intriguing small towns and hamlets, is an insidious truth that reveals the vicious cruelty and violence inflicted on certain residents.

That history reveals what happened in the best homes and the most well-respected families. It lasted, tolerated by nearly all, for more than 200 years.

Human beings were bought and sold, treated as property to be owned. They were enslaved and forced to live and labor under horrific conditions — legally — because the slave owners had white skin and the slaves were Black.

“The effect of ‘whitewashing’ the history of slavery in the North is more topical than ever, in light of the Black Lives Matter movement,” said Claire Bellerjeau.

Most people assume that slavery was prevalent in the American South, with its sprawling plantations, but not in the North. But in 1703, 42 percent of New York City households had slaves. By 1827, in Suffolk County, Long Island, one out of five residents was Black, and most of them were slaves.

From Oyster Bay to Glen Cove to Shelter Island to Southold to Setauket and beyond, Long Island — which included Suffolk and Queens counties before Nassau County was established — had “the largest slave population of the North for most of the colonial era,” according to Christopher Claude Verga, author of Civil Rights on Long Island.

LONG ISLAND’S SERVANTS

While most of the work slaves were forced to do was in agriculture, “slaves occupied every rung of skilled and unskilled labor,’’ wrote author Grania Bolton Marcus. The women labored mostly as domestic servants, while the men “cut stone, made barrels, blacksmithed, manned fishing boats and whaling ships,” she wrote.

Between 1755 and 1812, slavery was common in homes such as Raynham Hall, the residence of the Townsends, one of Oyster Bay’s founding families. The home is famous because Robert Townsend — George Washington’s spy — lived there. The family enjoyed the free labor of slaves who served their masters not only as domestic and field workers on the family’s 350-acre farm and on five merchant vessels; the slaves were forced to serve an enemy occupation of British officers in the house during the Revolutionary War.

“The effect of ‘whitewashing’ the history of slavery in the North is more topical than ever, in light of the Black Lives Matter movement,” said Claire Bellerjeau, director of education at Raynham Hall Museum (the Townsends’ former residence).

TECHNOLOGY SHINES A LIGHT

Forced to abide by strict rules, Black and Native American slaves were forbidden from running away, gathering in groups larger than three when not working for their owners, or showing what was called “stubborn pride.” If they disobeyed, their owners punished them — with government approval.

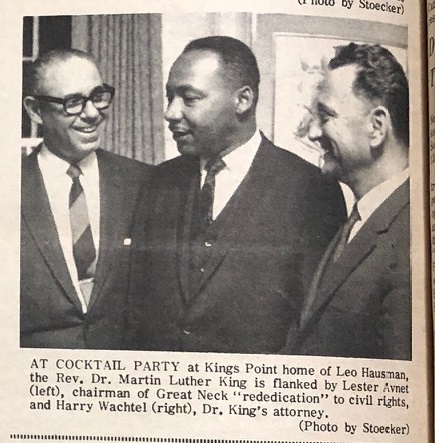

In the early 1700s, in the hamlet of Oyster Bay and across Long Island, residents would gather in the middle of town and watch as slaves said to be disobedient were restrained on a post and whipped — the most common punishment — often with 40 lashes. According to Town of Oyster Bay records, the public “negro whipper” was appointed by the town, and received as much as three shillings per slave.

Proof of this inhumane treatment was found by Bellerjeau. After the museum purchased the Townsend Family Bible in 2005, which belonged to the servants and listed details about the 16 “coloured people” owned by the family of Samuel Townsend in 1771, she searched previously unstudied museum archives from the late 1790s to the 1810s and found evidence of slavery in the North.

“To find two 19th century records of the actual act of a blacksmith describing doing such things to an enslaved person is groundbreaking,” Bellerjeau told the Press. “It directly refutes the long-standing misconception that somehow Northern slavery was less cruel than slavery in the South.”

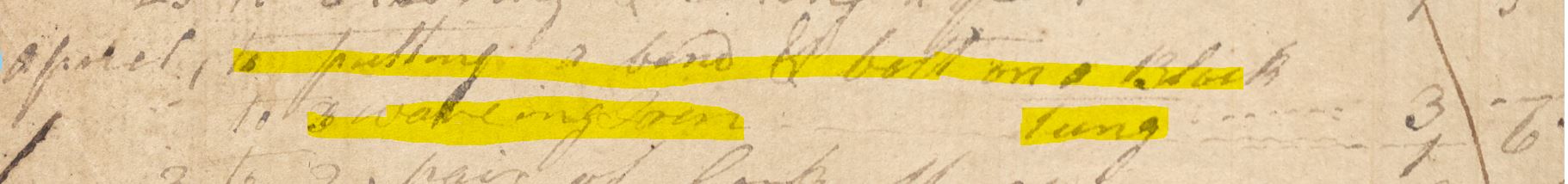

High-resolution scans illuminated the entries in blacksmith Daniel McCoun’s ledger of how slaves were controlled with iron collars and other restraints. One entry in the handwritten document described the act of “putting a band & a bolt on a Black” runaway slave for Thomas Youngs of Oyster Bay.

Another account revealed that in 1755, the blacksmith was paid 8 pounds by the Town of Oyster Bay to repair the irons (the manacles that restrained a slave on the whipping post); another entry included a charge for “12 nails and putting on,” said Bellerjeau. This practice, which Bellerjeau described as “even more gruesome,” detailed a type of torture dating back to medieval times: “breaking on the wheel.” The enslaved person was strapped to a wagon wheel, then beaten or even killed.

A CHANGE OF HEART

After the Revolutionary War ended, Robert Townsend became a founding member of the abolitionist New York Manumission (the act of freeing slaves by their owner) Society. The process of freeing slaves in New York State started gradually in 1799; by 1827, all slaves had been freed statewide.