(Photo by Jud McCranie/CC BY-SA 4.0)

Incidents from childhood can either make or break a person. Throughout our lives, challenges are placed in our paths, whether real or imaginary, and we find ourselves learning about the world and ourselves at the same time. Sometimes, the lessons are easy. Most of the time, they have the power to cause us to choose to sink or swim.

During family road trips, I often found myself gazing out the window at homes along our journey. A few homes had cement/ceramic “cats” upon their roofs to ward off birds and the mess birds left behind. Some homes had small statues of gnomes in their garden beds, while others had a massive clamshell with a saint or the Virgin Mary in the hollow. I often wondered why we did not have such “trinkets” in our beds, and Dad often told me such items would “get in the way of the lawn mower.” The beds in the front of our home were narrow, only wide enough to encompass a Mountain Laurel and a few small azalea bushes.

There was also the eyesore of the cesspool cover, so nothing else would fit in the area.

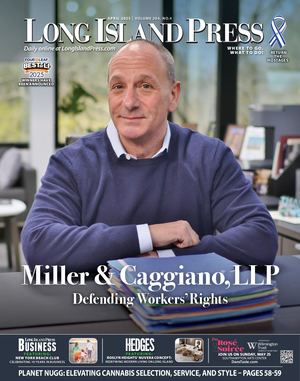

One item that always startled me was the lawn jockey. The figure, which was often a stooped-over POC who held a lantern or a hitching ring and was dressed in jockey clothing, always frightened me. The garish features were almost clown-like, and I disliked their appearance. When I asked Dad why people would even entertain such items by their doorsteps, Dad said, “It’s a matter of taste. Bad taste, but different strokes for different folks.”

As time went on, the lawn jockey statue, which was comprised of iron or solid cement, became more slender and taller, with less jarring features. I still did not like the yard ornament and told my father that I should never want one of my own. I found it offensive.

Fast forward to this week, when one of Hicksville’s own offered a brief history on the topic. As legend has it, the shorter version, known as “Jocko,” was given birth by an idea of George Washington’s as a commemoration to a young man who served with General Washington during his crossing of the Delaware River. The general asked the boy to stay along the riverbank with his lantern, as the impending surprise attack on the Hessians in Trenton, NJ, would prove to be too dangerous for his young years. True to his word, young Jocko Graves stood upon the shore of the Delaware until he was found frozen to death the following morning, his lantern still in his right hand. It is said that Washington, who was moved by the young boy’s loyalty, had a statue created, known as “The Faithful Groomsman” and installed it at his Mount Vernon Estate.

There are no records of Jocko Graves in any historical chronicles, army records or other history to corroborate this story.

Legend also has it that these lawn jockeys were placed upon the lawns of homes that were considered “safe” for those who sought freedom along the Underground Railroad. Charles L. Blockson, Curator Emeritus of the Afro-American Collection at Temple University, stated that green ribbons were tied to the arm of the jockey, which signaled safety, while red ribbons advised those fleeing slavery to keep going. Further legends state that the shirt color of the jockey was significant; striped shirts meant that it was safe to swap horses, while a tailed coat meant overnight lodgings and food were available. A blue sailor’s waistcoat meant the homeowner could take you to a port to get you to a ship bound for Canada.

This story has been disputed over the years, most especially in the book, Culture Wars: An Encyclopedia of Issues, Viewpoints and Voices. The Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia also stated that there is nothing about lawn jockeys having anything to do with the Underground Railroad Movement. The debate continues to this day.

In Saratoga Springs, the “Cavalier Spirit” lawn jockey is often placed on the lawn of summer residents to let year-round residents know that they are back in town. These more brightly colored statues, who hold a hitching ring in their left hand, are tightly bound to the town’s racing spirit and are a huge part of Saratoga Springs’ landscape.

To be honest, these statues, whether in the “Jocko” form or the taller “Cavalier Spirit” version are offensive to a lot of folks. They are still in demand and one manufacturer of these statues states that he has shipped more than 200 overseas. However, there are still many who find the statues rather cringe-worthy, off-putting and racist.

Regardless of the true or false history behind the lawn ornament, lawn jockeys have been a part of the American landscape for more than 200 years. As Franklin Hughes of the Jim Crow Museum stated last year, “In my opinion, a powerful narrative is the rising and achieving of African Americans despite hundreds of years of resistance in this culture. To operate in a society that is slanted against you, in imagery and all other ways that matter, and still one rises, is a testament to the heroic intestinal fortitude.” Well said, sir. Well said.

Patty Servidio is an Anton Media Group columnist.