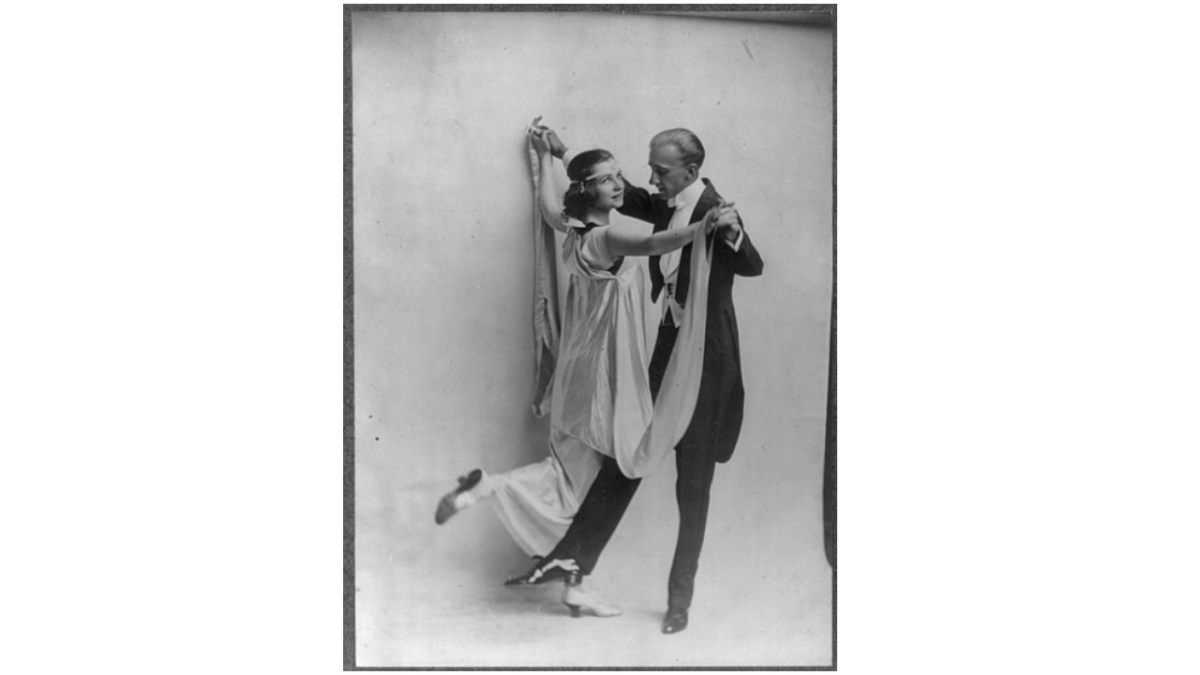

Young, attractive, talented, and in love, they twirled themselves into the hearts of audiences. America’s sweethearts — and trendsetters — Vernon and Irene Castle revolutionized dance and fashion.

They kicked up their heels while standing their ground, challenging prevalent racist attitudes and advocating for animal rights. Even as World War I broke out, they brought the country a sense of fun and tolerance for all.

They were not always so fortunate: They started out broke and unemployed, living in a cramped apartment with three beloved dogs. Then success hit: Poor no more, they purchased a 5,000-square-foot waterfront mansion on Long Island’s Manhasset Bay, a fitting home for them and their resident animals large and small.

TWO TO TANGO

Vernon Castle Blythe was an Englishman performing in Manhattan as a magician, actor, and dancer when he met Irene Foote in 1910 at suburban New Rochelle’s Rowing Club. He was 23, she 17. A New Rochelle native, she had grown up with show-business types, as her grandfather was a Barnum & Bailey Circus press agent. A high school dropout, she spent time dancing and singing in amateur theatricals.

They were married in 1911 and by 1912 were starring in a Broadway revue. They sailed to Paris and performed their first ballroom routine, to Irving Berlin’s Alexander’s Ragtime Band. Ragtime, the African American forerunner of jazz built on syncopated rhythms, would never be the same.

The Cafe de Paris hired them and their career took off, fueled by publicity, a new marketing tool. They sailed back to New York to perform and develop dances based on African American music styles — the one-step, turkey trot, grizzly bear, Castle walk, Castle polka, glide, hesitation waltz, bunny hug, innovation tango, and scads more.

They bucked Puritan beliefs, as Douglas Thompson wrote in Shall We Dance? The True Story of the Couple Who Taught the World to Dance: “Fiery preachers across Europe and especially in America denounced ballroom dance as the devil’s work … The idea that men and women should dance so close together was evil.”

But their appearance banished those attitudes, wrote Thompson: “You too could be slim and healthy and in love — if you danced.” Irene said she personified the girl next door, and they were “young, clean, married, and well-mannered.” They delighted in dancing together, their arms encircling each other, dipping, bowing, hopping, arching — and making it look simple.

BEYOND BALLROOM

There was more to these stellar performers than fancy footwork. They skipped across upper-crust society with backstage behavior that elevated them as pioneers in social attitudes.

Traveling with a Black orchestra, James Reese Europe’s Society Orchestra, the Castles believed that only Blacks could comprehend ballroom dance music’s rhythms. But segregation was prevalent. Blacks weren’t allowed to occupy whites’ train cars or enter nightclubs. Still, Castle persisted, and succeeded. The Castles introduced audiences to Black musicians through touring and endorsing their phonograph records.

Over the next few years, the Castles opened a dancing school, Castle House, across from Manhattan’s Ritz Hotel; their supper club, Castles in the Air, was located on a Broadway theatre’s roof. They performed on Broadway and made films, splitting their time between the City and Long Island.

They indulged their love of animals by purchasing Shorecliff House in 1914, a 4.5-acre estate on Manhasset Bay, with kennels and stables for 24 dogs, five horses, a donkey, and more, including animals rescued from the theater. The same year, they opened a resort/dancing school, Castles by the Sea, on the Long Beach boardwalk on Long Island’s South Shore (now the site of the Allegria Hotel).

By 1915, Irene had become a fashion leader: She danced in long, floating skirts and distinctive headwear, bobbed her dyed-red hair, and discarded her girdle. When Vernon returned to England to support the war effort by flying combat missions, she continued performing but was unhappy dancing solo. He returned to America to train pilots, but died in a Texas plane crash in 1918.

Her career mostly ended in 1923, except for summer stock, after she remarried and relocated to Chicago. In the late 1920s, she was labeled “The best-dressed woman in America,” but animal rescue was her passion. The antivivisectionist activist founded the Illinois dog shelter Orphans in the Storm.

In 1964 she told The New York Times: “When I die, my gravestone is to say ‘humanitarian’ instead of ‘dancer.’ I put it in my will. Dancing was fun, and I needed money, but Orphans in the Storm comes from my heart. It’s more important.”

She died in 1969 and is buried next to Vernon Castle at Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx.

To see the Castles doing the Castle Walk, from the 1914 silent film The Whirl of Life, visit youtube.com/watch?v=qkqf9_Wr_Vs

Sign up for Long Island Press’ email newsletters here. Sign up for home delivery of Long Island Press here. Sign up for discounts by becoming a Long Island Press community partner here.