It’s that time of year when singer-songwriter Steve Earle is getting ready to pack up and hit the road after spending the prior nine months as a single dad for his son John Henry, who is autistic and attends a special needs school in Manhattan. But as has been the case everywhere, COVID-19 threw a major monkey wrench into the plans of the world. The metaphorical pause button hit by the pandemic wreaked even more havoc for touring musicians, who make their money on the road and were instead forced to stay home as that part of the music industry ground to a complete halt.

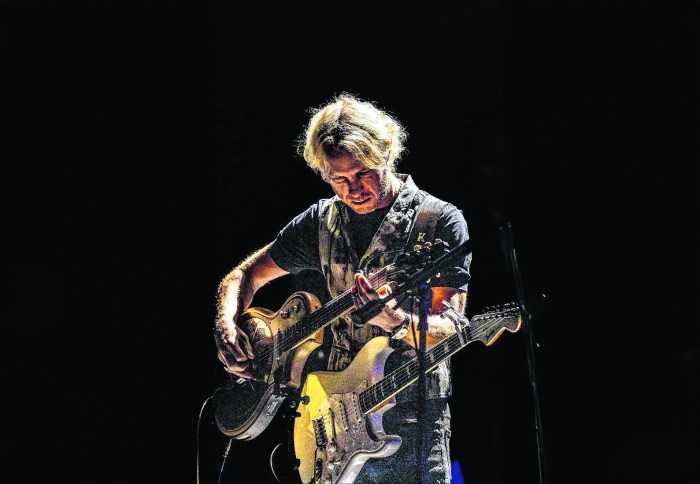

(Photo by Gus Philippas/CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Prior to the planet coming under a coronavirus lockdown, Earle was the musical director for Coal Country, a play by Jessica Blank and Erik Jensen that centered on the 2010 West Virginia Upper Big Branch mine explosion that killed 29 men and tore that community apart. It was a production at Manhattan’s Public Theater and was Earle’s latest foray into theater following his involvement with playwright Richard Maxwell’s 2017 Off Broadway play Samara, where the Texas native wrote the score and had a bit part in the cast. While Earle has made his mark as an Americana singer-songwriter, his interest in theater dates goes back a couple of generations in his family.

“My grandmother was the seamstress in the drama department of a teeny, tiny junior college in Northeast Texas called Lon Morris College and they did a musical, a straight play and Shakespeare every year,” he said. “They had a nice little traditional proscenium theater and Tommy Tune came out of that school actually. It always stuck with me. Theater has always been a big deal to me. When I moved [to New York City], I had a theater company in Nashville for a minute that started because of a girlfriend that was an actor. We did death penalty stuff together and that turned into a not-for-profit theater together in Nashville, which was a lot of money and a lot of work. With Coal Country, that was four years from when Jessica [Blank] and Erik Jensen and I traveled to West Virginia and they did the interviews with the people that were portrayed in it and I started writing the songs there at that point. It took four years to get it on stage.”

“My grandmother was the seamstress in the drama department of a teeny, tiny junior college in Northeast Texas called Lon Morris College and they did a musical, a straight play and Shakespeare every year,” he said. “They had a nice little traditional proscenium theater and Tommy Tune came out of that school actually. It always stuck with me. Theater has always been a big deal to me. When I moved [to New York City], I had a theater company in Nashville for a minute that started because of a girlfriend that was an actor. We did death penalty stuff together and that turned into a not-for-profit theater together in Nashville, which was a lot of money and a lot of work. With Coal Country, that was four years from when Jessica [Blank] and Erik Jensen and I traveled to West Virginia and they did the interviews with the people that were portrayed in it and I started writing the songs there at that point. It took four years to get it on stage.”

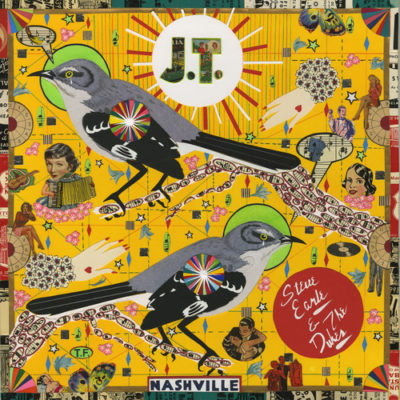

Someone who can be charitably referred to as restlessly creative, Earle was no less busy throughout the pandemic-generated lock-down. In addition to rereading all of Harry Potter and His Dark Materials, watching his beloved New York Yankees and creating a YouTube show called Guitar Town with Steve Earle (“It’s like an eight to 15-minute cooking show for guitar nerds”), he also met with Horton Foote’s daughter about collaborating on a Tender Mercies musical. The most difficult task the Texas native grappled with was recording 2021’s JT, a project he embarked on following the accidental drug overdose of his son Justin Townes Earle on Aug. 20, 2020 at the age of 38.

The album consists of songs either written or co-written by the younger Earle (with the exception of the Steve Earle-penned closer “Last Words” penned a few days after his son’s death). In the liner notes, Earle shared the purpose for the release. “For better or worse, right or wrong, I loved Justin Townes Earle more than anything else on this earth. That being said, I made this record, like every other record I’ve ever made…for me. It was the only way I knew to say goodbye.” And while his son’s death was understandably too raw to discuss, Earle made it clear that this current tour is focusing more on Earle’s 2020 release.

“This is not going to be a JT tour,” he explained. “We have the Ryman Auditorium for Jan. 4 of next year, which would have been Justin’s 40th birthday, that way I’ll get a lot of help. We’re going to do three or four songs from JT—probably three to start out with. I can’t do a whole set of that stuff. Right now, I can’t do it and I may not ever be able to. Originally, I thought this was going to be a Ghosts of West Virginia tour because I want those people’s stories to be told. I finally started putting the set list together with what we’re going to start with. The t-shirt sales go to West Virginia. We’re also selling a print of the JT cover and will be selling both albums on the road. What this will be is a post-pandemic tour—it’s just basically the set that was designed to play the songs people want to hear and to get me girls. So that’s it.”

“This is not going to be a JT tour,” he explained. “We have the Ryman Auditorium for Jan. 4 of next year, which would have been Justin’s 40th birthday, that way I’ll get a lot of help. We’re going to do three or four songs from JT—probably three to start out with. I can’t do a whole set of that stuff. Right now, I can’t do it and I may not ever be able to. Originally, I thought this was going to be a Ghosts of West Virginia tour because I want those people’s stories to be told. I finally started putting the set list together with what we’re going to start with. The t-shirt sales go to West Virginia. We’re also selling a print of the JT cover and will be selling both albums on the road. What this will be is a post-pandemic tour—it’s just basically the set that was designed to play the songs people want to hear and to get me girls. So that’s it.”

While Earle will continue writing and recording music, his creative itch continues to point him in the direction of other outlets be it a science fiction television pilot he’s writing and pitching (Heinlein, Bradbury and Asimov are favorite authors) or his continued foray into musical theater, a pursuit he admits to pursuing with deference.

“I was basically very careful about it and respectful because it’s not lost on the theater community that the record business didn’t give a [damn] about them,” he said. “And then all of a sudden, our business falls apart and we come to New York like rats from a sinking ship. A lot more famous songwriters than I am have been handed their heads trying to get on Broadway. Cyndi Lauper kind of cheated because she did her first show with Harvey [Fierstein] from the beginning. Everybody else got their asses kicked—Paul Simon, Sting—everybody else that’s ever tried to do that. So I was very careful about that. It turns out that the two things I was in were well reviewed and I got a [frigging] Drama Desk Nomination for Coal Country. I think I’ve been accepted to some degree in the theater community in New York. Then everything shut down. It could be real easy to feel sorry for yourself but that happened to the whole world. New York and theater are already coming back faster than people thought.”

Politics is never far from Earle’s mind or mouth, so it’s no surprise that he sees the story behind Coal Country as being a reflection of the country’s current cultural divide, one that he’d love to help breach.

“I want to rehabilitate redneck, awesome and genius—those are three words nobody knows what the [hell] they mean anymore,” he said with a laugh. “We got a lot of [crap] for Coal Country because of its carbon footprint. It didn’t have a carbon footprint. It had a human footprint. People in the middle of the country need to understand why people on either coast think the way they do. And folks on the other side have got to try harder—a lot of friends of mine are constantly trying to triumph the working camp and they don’t even know what that is. Or how it works once they get out of their backyard. People are fond of saying that people vote their pocketbooks. That’s not true. Rich people vote their pocketbooks. Working people vote their hearts. They’re voting for their families. West Virginians voted for Trump because the only people they knew that had anything were people that worked in coal. If you can’t work in coal, you were unemployed, on the dole and probably addicted to oxycontin. That’s what’s been going on in West Virginia for a long, long time. It’s just like it is everywhere else.”

Steve Earle and the Dukes will be headlining the 7th Annual John Henry’s Friends Benefit on Dec. 13 at Town Hall, 123 W. 43rd St., NYC. Visit www.the-townhall-nyc.org or call 212-307-4100 for more information.