St. Patrick’s Day is both a celebration of faith and a triumph of the human spirit.

In addition to his theistic mission, St. Patrick brought the gifts of classical antiquity to the Emerald Isle, enduring privation and enslavement: “So I live among barbarous tribes, a stranger and exile for the love of God.”

But centuries later, the grace of St. Patrick would be forgotten by some who claimed to revere him.

In An Unlikely Union: The Love-Hate Story of New York’s Irish and Italians, Paul Moses reveals, “Rather than try to unify the congregations, Irish-American pastors found it better to make Italians worship in the church basement.”

Yet the Irish and the Italians share an ancient bond: St Patrick.

Patricius was the privileged son of Calpurnius and Conchessa, Romans living in Britain. In Roman Britain: Outpost of The Empire, H. H. Scullard notes that “the story of St. Patrick, who returned home after being carried off by Irish raiders in his youth, shows that his father’s villa (in the Bristol Channel area?) was still functioning circa 430 A.D.”

The man who would become Ireland’s patron saint was fluent in Latin and a devotee of Virgil’s Aeneid. And St. Patrick was steeped in the history of the Caesars.

Archaeological evidence points to a Roman base at Tipperary. Historians believe that extensive cultural and trade ties existed between Italy and Ireland. The unearthing of a Roman fort at Drumanagh, north of Dublin, points to an Italian presence on the Emerald Isle between 79 and 182 A.D.

According to Tacitus, Julius Agricola — Rome’s governor of Britain from 78 to 84 A.D. — hosted an exiled Irish prince named Tuathal Techtmar. And in 82 A.D., Agricola traversed the Irish Sea and defeated a band of Hibernians, boasting that the conquest of Ireland could be achieved with but one legion and some auxiliary troops. (Historians Barry Raftery and Gabriel Cooney contend that he used another recently discovered fort near Dublin as his base of operations.)

However, conquest has many facets. From the Roman citadel of Cashel (castellum) in Leinster to the military-religious complex in Tara to Saint Palladio’s church in Tigroney — Teach-na Roman (House of the Romans) — to St. Patrick’s foundational mission, Ireland fell under Rome’s cultural dominion, adopting the Latin alphabet and becoming a most enlightened isle.

St. Patrick’s Day is a feast for all those who honor the West and its egalitarian values.

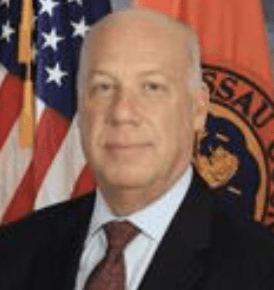

Rosario A. Iaconis is an Italian Heritage Educator at Suffolk County Community College.

Sign up for Long Island Press’ email newsletters here. Sign up for home delivery of Long Island Press here. Sign up for discounts by becoming a Long Island Press community partner here.