“The first thing I do in the morning is brush my teeth and sharpen my tongue.”

“I’d rather have a bottle in front of me than a frontal lobotomy.”

“It serves me right for keeping all my eggs in one bastard.”

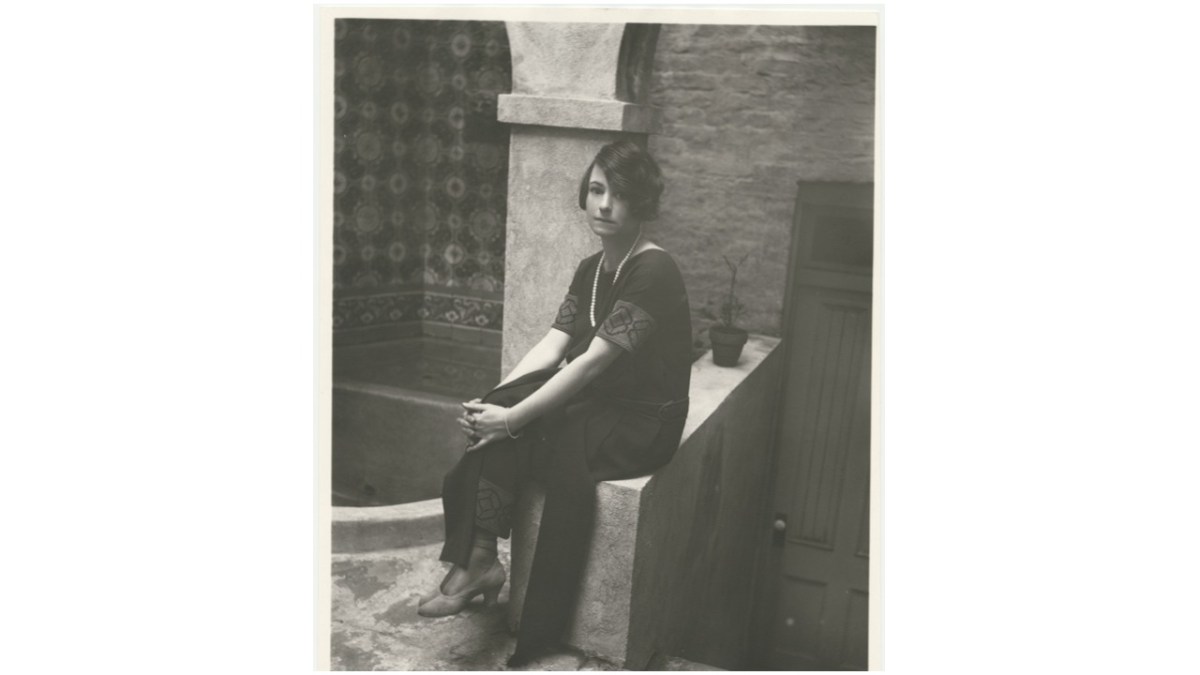

These are just a few of poet-critic-screenwriter Dorothy Parker’s popular zingers. Best remembered for sharp-witted verse and wisecracks, she was also a self-proclaimed feminist who mocked sexist attitudes, and a human rights advocate who was accused of being a Communist.

She frequented Long Island, as a child and during the Roaring ‘20s, when she and her cohorts from the famed Manhattan literary circle the Algonquin Round Table headed east every weekend.

Nothing was safe from her quips or commentary, not even her childhood: As The New York Times reported, she recalled being “a plain disagreeable child with stringy hair and a yen to write poetry.”

“BUT, BY GOD, I READ.”

She was born Dorothy Rothschild (no relation to the Rothschild dynasty) in 1893 in West End, N.J., to a Scottish mother and Jewish father. Their daughters spent summers at the Wyandotte Hotel in Bellport on Long Island’s South Shore, exchanging poetry and postcards with their widowed father, who asked that his daughters write to him daily.

The young poet was enrolled in private schools, but she left school at age 15. As writer/editor Jack Limport wrote, she told another reporter, “Because of circumstances, I didn’t finish high school. But, by God, I read.”

After her father died in 1913, 21-year-old “Dottie” supported herself as a pianist for dance schools, which thrived thanks to the tango and other dances sweeping the country.

And she wrote: She sold her poem Any Porch to Vanity Fair magazine for $12 in 1914. Its sister publication Vogue hired her to write captions for illustrations; her $10 weekly salary paid for her $8-a-week boarding house lodging.

She became a Vanity Fair staff writer and by 1918 was Broadway’s only female drama critic, writing often-lethal reviews. One book review said, “This is not a novel to be thrown aside lightly. It should be thrown with great force.” Of film actress Marion Davies, Parker wrote that she had “only two expressions, joy and indigestion.”

Parker’s barbs got her fired in 1919, but she freelanced for the Saturday Evening Post and other publications and became The New Yorker’s drama critic.

“THE GUNK” GOES EAST

Because of her writing reputation, she became the only female founding member of the Round Table. On weekends at Correspondent Herbert Bayard Swope’s turreted, gabled Gold Coast mansion in Great Neck, comedian Harpo Marx, humorist Robert Benchley, the Duke and Duchess of Windsor, the Fitzgeralds, and others joined Parker.

The gang caroused, gambled, and drank — despite Prohibition being in effect — and played croquet on the great lawn overlooking the bay in Great Neck, according to biographer Marion Meade, and celebrated in Cold Spring Harbor at arts patron Otto Kahn’s 126-room French chateau.

Parker didn’t drive, instead taking the Long Island Rail Road. According to The New York Times, she complained that “If she ever took a nonstop transatlantic journey she would still have to change at Jamaica.”

UNREST AND ARREST

She was successful, but full of self-doubt. As The Times reported, she couldn’t “write five words without changing seven.” Cynical and depressed, she missed deadlines. Squandered advances. Attempted suicide.

She demanded equal pay for equal work, writing, “My idea is that all of us, men as well as women, should be regarded as human beings.” After Italian Americans Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti were convicted of murder based on circumstantial evidence, she championed civil liberties and civil rights. She was arrested after marching and singing the party anthem at a 1927 rally before the immigrants’ execution, according to Smithsonian Magazine. Although not a member of the Communist Party, she helped organize the Anti-Nazi League and the Screen Writers Guild, viewed by the FBI as Communist fronts.

Despite her cynicism and depression, she kept writing what The New York Herald Tribune called “whiskey straight” verse. In 1929 she received the O. Henry award for her short story Big Blonde, a feminist critique of American society. She continued her criticisms: Time magazine reported in 1934 that “during an intermission of The Lake, Dorothy Parker remarked … ‘Well, let’s go back and see Katharine Hepburn run the gamut of human emotion from A to B.’”

In 1938 she was nominated for an Oscar for co-writing the screenplay for A Star is Born; she was nominated again in 1948 for co-writing the original motion picture story for Smash-Up: The Story of a Woman. In 1949, she was blacklisted and never worked in film again.

Parker died of cardiac arrest in 1967 at age 73. Her lifelong friend writer Lillian Hellman said that Dottie wanted her tombstone to say, “If you can read this, you’ve come too close.”

For more Rear View columns on Long Island history, visit longislandpress.com/category/past-present/rear-view

Sign up for Long Island Press’ email newsletters here. Sign up for home delivery of Long Island Press here. Sign up for discounts by becoming a Long Island Press community partner here.