It is a nightmare scenario: A plane crashes in the Sahara. Stranded, badly injured, the pilot barely subsists, trekking across the sands for days until a desert tribesman rescues him.

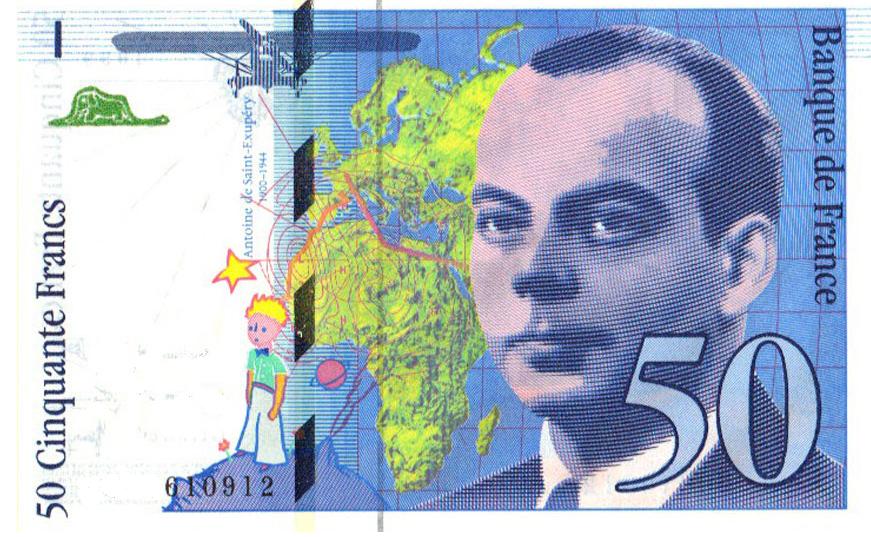

This is not a bad dream; it is the true story of Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, an aviator-author trapped in a harsh, forbidding reality in 1935. And although his plane was downed, his inspiration was not: The accident inspired his beloved novella, The Little Prince.

Seven years later, he completed his imaginary tale of the prince, an innocent young explorer. The vision sprang to life through the simple words and delicate illustrations he created after escaping from wartime France and immersing himself in the tranquility of Long Island’s North Shore. His fable served as his antidote to war.

FLYING AND FANTASY

Born in 1900 and raised in two beautiful chateaux in Lyon, France, Saint-Exupéry was a poor student and a willful, unruly child. But the imaginative boy with golden curls lived a childhood full of fantasy and composed poems at a young age. His other passion was the concept of flight: At age 12 he tried to construct an airborne bicycle.

After joining the French military at age 21, he combined his dual passions, writing about his adventures in the air force and then as a mail pilot, flying all over western Europe and North Africa, according to the National World War II Museum.

Flying for the French air mail service Aéropostale meant long hours of tense solitude in the cockpit; as The New Yorker put it, “Pilots were at the mercy of sandstorms, snow, and freak winds, flying low through mountain passes and over mile after mile of desert.”

Crash landings were common. In 1923, a crash fractured his skull. In 1935, he crashed in the Libyan desert with his navigator-flight engineer Andre Prévot. They wandered for four days, consuming wine, coffee, fruit, crackers, and chocolate. Dehydrated and sun exposed, they were rescued by a Bedouin tribesman on a camel. While recuperating, Saint-Exupéry wrote about the experience in his 1939 memoir Wind, Sand and Stars, as World War II began in Europe.

When France collapsed under Nazi occupation in 1940, he and his wife Consuelo fled to Manhattan. But the city was too noisy, too distracting for the survivor plagued by stress and the severe injuries sustained in flying accidents.

FLIGHT TO TRANQUILITY

At Bevin House, a Victorian mansion in placid Asharoken near Northport on the Long Island Sound in the summer of 1942, he attempted to make sense of the war in The Little Prince.

He created a mystical child hero, a golden-haired boy wiser than any grown-ups. The child has left his tiny planetoid, an asteroid no bigger than a house. He descends to Earth, where a talking fox tells him, “If you tame me, then we shall need each other.” The boy befriends a stranded pilot, who learns from this fragile treasure who says, “People have no imagination. They repeat whatever one says to them.” The elfin figure tells the despairing aviator, “It is only with the heart that one can see rightly; what is essential is invisible to the eye.”

In an interview by Ed Carr, who wrote Faded Laurels, about Asharoken and Eatons Neck, the home’s owner May Cornell Bevin recalled, ”When the sun came up in the morning, Saint-Exupéry kept an easel in the library and would work on sketches and watercolors … As the sun moved across the sky, he’d move with the sun toward the parlor, where there was light. Then he’d write in there.’’

He was so inspired staring out at Duck Island Bay while writing the story and laying down the watercolor hues that he mentioned Long Island in an early version of the 1943 child’s fable for adults. The book became one of the bestselling books in the world.

FINAL FLIGHT

A few weeks before Paris was liberated in 1944, Saint-Exupéry, back in France, took off from the Mediterranean island Corsica to take reconnaissance photographs. He was never heard from again.

The hypotheses flew: Did a German pilot shoot down the plane? Did Saint-Exupéry lose control of the aircraft? Did he commit suicide? As The New Yorker reported, he was overweight, in poor physical condition, and drinking heavily to dull the pain from old injuries.

Nearly 60 later, in 1998, his identity bracelet and aircraft wreckage were discovered, far off his flight path. Archaeologists found no evidence that his plane had been shot down and no body. But in 2006, marine archaeologist Luc Vanrell located a former German pilot, Horst Rippert, who confessed, “You can stop searching. I shot down Saint-Exupéry,” according to The New York Times.

Rippert said he did not know whom he had shot because he couldn’t see the pilot. Ironically, Rippert had idolized Saint-Exupéry and read his books. The Times reported that a spokesman for the author’s family later said of Rippert, “If he had known what he was doing, he never would have done it.”

For more Rear View columns on Long Island history, visit longislandpress.com/category/past-present/rear-view.

Sign up for Long Island Press’ email newsletters here. Sign up for home delivery of Long Island Press here. Sign up for discounts by becoming a Long Island Press community partner here.