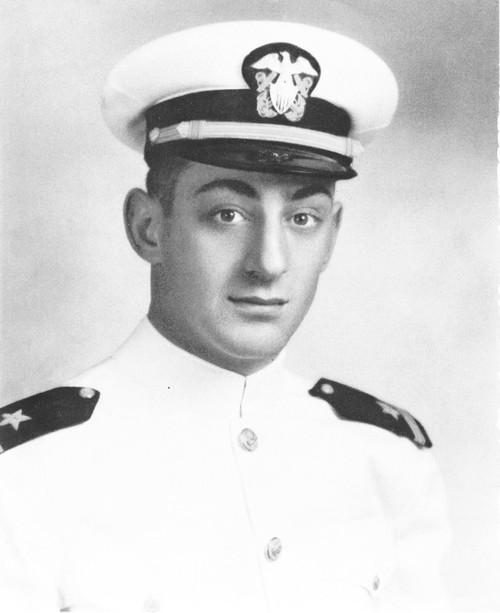

Throughout his life, Harvey Milk’s family often said, “When … evil descends on the world, you have to fight, even when it’s hopeless.” And so he spent his life battling evil. He was honored in books, an opera, a postage stamp, an Oscar-winning motion picture, and a documentary. A U.S. Navy warship, streets, and parks bear his name. In 2019, his image was immortalized on the tail fin of a Norwegian Boeing 787 Dreamliner aircraft.

Norwegian airlines summed up the reason the native Long Islander drew such attention: He ”fearlessly pursued the freedom for every human being to live life with authenticity and courage.”

“WE MIGHT BE ON THAT LIST”

When Mausche Milch, Milk’s grandfather, came to America from Lithuania in 1897, he anglicized his name to Morris Milk. Settling in Woodmere, he bettered the community, opening its first department store and co-founding its first synagogue.

But by the early 1920s, the region was rife with antisemitism. Members of the white supremacist terrorist group the Ku Klux Klan drew tens of thousands to rallies. The local country club banned him and and other Jews from joining, citing its “no Jews” policy. The resourceful man retaliated, helping to establish a Jewish country club.

His grandson Harvey Bernard Milk was born on May 22, 1930. The child saw his family repel evil firsthand: In the 1930s, when the school board rejected a teaching applicant because she was Jewish, his father Bill Milk joined other Jewish parents, demanding that the board hire her.

As Harvey later said, “Jews know we can’t allow discrimination—if for no other reason than we might be on that list someday.”

He attended Bay Shore Senior High School, an outgoing student with diverse interests: He worked at Milk’s, the family store; played football and basketball; loved opera, attending a Metropolitan Opera performance as a teenager; and he was the class clown. He realized he was gay, but kept that to himself.

After graduating in 1947, he attended the New York State College for Teachers (now State University of New York at Albany). In the student newspaper, he wrote about World War II and the Nazis’ deadly persecution of Jews, Blacks, Roma, and gays. He graduated in 1951 and served in the U.S. Navy until 1955; some biographers say he received an “other than honorable discharge” for engaging in sexual acts with men, others say he resigned after being officially questioned about his sexual orientation. For several years he taught at George W. Hewlett High School on Long Island and worked as a stock analyst and production assistant for Broadway musicals including Jesus Christ Superstar.

During the 1960s unrest that fractured the country, he embraced advocacy, demonstrating against the Vietnam War as well as police and state harassment of LGBTQ communities.

Then came Stonewall.

THE MAYOR OF CASTRO STREET

Police raided the Stonewall Inn, a popular Greenwich Village gay bar, on June 28, 1969, arresting employees they said were selling alcohol illegally, checking customers for what they deemed gender-appropriate clothing, and forcing anatomical inspections on some cross-dressers. Word spread, and hundreds protested for days and nights. The Gay Liberation Front was born, and New York City’s Pride march debuted in 1970.

In San Francisco, bullhorn in hand, Milk burned his BankAmericard, because the bank was financing companies that produced goods and material used in the war, according to The New York Times. He was fired from his financial analyst job.

In 1973, settling for good in San Francisco, the civil rights leader opened Castro Camera and co-founded the Castro Village Association, an organization of LGBTQ-friendly businesses. The burgeoning gay population dubbed him “the mayor of Castro Street,” rallying behind his challenging what he termed the city’s conservative gay leadership.

“If a bullet should enter my brain, let that bullet destroy every closet door in the country,” Harvey Milk said a year before his assassination.

He ran for office several times, espousing what The New York Times called “a broad platform that embraced expanded childcare facilities, free municipal transportation, low‐rent housing, and a civilian police‐review board, rather than primarily the issue of homosexual rights.” In 1977, winning a seat on San Francisco’s Board of Supervisors, the activist became the first openly gay man elected to California public office.

He successfully worked to ban discrimination based on sexual orientation in 1978, the year the Pride rainbow flag was designed. Fighting against Proposition 6, which sought to ban gay teachers and gay-rights sympathizers from schools, he told one audience, “I cannot remain silent anymore,” and lamented that “There was silence in Germany because no one got up early enough to say what Hitler really was. If only someone did, maybe the Holocaust would never have happened.”

DEATH THREATS DAILY

After taking office in January 1978 he said, “There is no law that says that two human beings can’t love one another.” Receiving death threats daily during nearly 11 months in office, he recorded this message: “If a bullet should enter my brain, let that bullet destroy every closet door in the country.”

Milk, age 48, and Mayor George Moscone were assassinated in San Francisco City Hall by Dan White, a conservative former city supervisor, on Nov. 27, 1978.

The 2022 Long Island Pride celebration takes place on Sunday, June 12th from 12n-6p in the Village of Farmingdale. The annual parade, concert, and festival recognize the impact that lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender individuals have had on history, and is the first full in-person Pride since 2019. Learn more at lipride.org.

For more Rear View columns on Long Island history, visit longislandpress.com/category/past-present/rear-view.

Sign up for Long Island Press’ email newsletters here. Sign up for home delivery of Long Island Press here. Sign up for discounts by becoming a Long Island Press community partner here.