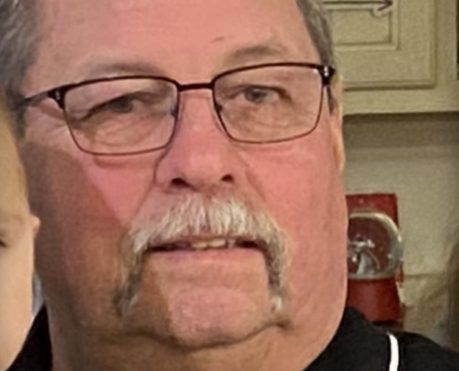

Many people know Fred Guttenberg, an East Northport native, as a passionate advocate against gun violence. He grew up on Long Island and, like many Long Islanders, moved to Florida. When his brother died of a disease related to the Sept. 11, 2001 attacks, he and his family faced a terrible tragedy. But sorrow, unlike lightning, often strikes a second time. His daughter Jaime was killed at age 14 in the Feb. 14, 2018 school shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Fla.

Since then, Guttenberg has appeared in town halls, debated gun violence, spoken out and been part of a push that led to legislation. And he has become a key figure in efforts to pass new legislation related to guns, referring to “gun safety,” not gun control, in a battle that includes language.

“Since my daughter Jaime was murdered in Parkland, I have tried to engage gun owners and dads to support doing more,” he tweeted after the recent elementary school massacre in Uvalde, Texas.

Democrats and Republicans recently reached a compromise that would lead to enhanced background checks for those ages 18 to 21 among other changes. For Guttenberg, this was at once political and personal.

“We broke a 30-year log jam, 30 years when nothing was done,” he recently said on MSNBC. “This is a breakthrough 30 years in the making. It does deliver a way to look at the 18-to-21-year old group differently. It does so many things that will save lives and reduce the instances of gun violence.”

U.S. Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) called the legislation a “commonsense package of popular steps that will help make these horrifying incidents less likely while fully upholding the Second Amendment rights of law-abiding citizens.”

Guttenberg tweeted that “we will never know the families who will benefit from this legislation, or the people who did not die because of this legislation,” but said the legislation would save lives.

“Now, we will continue working at this,” he said, “as nothing is more important than saving lives.”

Passion for change

Possibly the best-known advocate for gun safety from LI, Guttenberg has long supported regulation ranging from gun storage laws to background checks. The phrase “gun control” has become highly politicized, and he says there are differences.

He says the new gun legislation, which passed the House of Representatives a day after the U.S. Senate approved it, is “not everything we would have wanted,” but it breaks a logjam in place for decades, even amid protests and proclamations.

Guttenberg has been working to keep gun violence an important issue, as school shooting follows school shooting, amid a supermarket shooting in Buffalo, and shootings occur across the nation with a numbing regularity. He speaks as a father, a fighter and someone on a mission to prevent other parents from losing their children. In a way, he is focusing on America’s other epidemic, in addition to COVID-19 and drugs.

At a time when the annual death toll due to guns in the United States has surpassed those due to car collisions, topping 40,000 — more than 100 a day — Guttenberg and others seeking to battle gun violence have been trying to figure out how not only to be heard, but to make things happen to increase safety.

There were 45,222 firearm-related deaths in the United States in 2020, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. While there’s a lot of focus on people shooting each other, suicide is a big part of the toll. About 54 percent of those deaths were suicides and about 43 percent were homicides, ranking firearms among the top five causes of death for United States citizens up to age 64.

“I’ll talk to anyone. They don’t have to agree with me,” Guttenberg said on a little reported trip back to the Island two years ago at a conference sponsored by the Donald and Barbara Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell Health. “When we get done, they’ll have a better understanding of who I am and why it matters.”

The medical school brought Guttenberg in to talk about the personal toll of gun violence, as a medical, not a political issue. He spoke at length at this event to an audience of future doctors as someone on a mission to reduce the gun violence that had already taken his daughter’s life.

“She went running down the hall from an active shooter and made it to within one second of survival,” he said at that event. “People always say to me, ‘I can’t imagine how you feel.’ I hear that phrase every day.”

It’s a phrase that many parents in similar situations have heard, most recently in Uvalde, as well as relatives of victims shot in a Buffalo supermarket shooting, as ordinary places become scenes of horrific violence. Guttenberg had never been an activist until in one moment he lost his daughter and found a mission that consumes his life to this day. Just days after gun legislation passed, it may be timely to look at Guttenberg’s own journey, and what it’s like to face such a personal loss and try to achieve change, at a time when the country is so polarized about so many things.

From 9/11 to now

While Guttenberg has no medical degree, he has been seeking to save lives, something his brother, Dr. Michael Guttenberg, did many times. That had long been the mission of Guttenberg’s brother, who headed emergency medicine for Northwell and died in October 2017 of cancer related to 9/11.

“My brother was one of the doctors who ran the triage. He was at the World Trade Center when it collapsed. Amazingly, he survived that,” Guttenberg said. “Like all heroes, instead of running and getting out of there, he spent the next 16 days at Ground Zero.”

Dr. Michael Guttenberg was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer and declared cancer-free for a few years before it came back in 2016. Fred Guttenberg sold his business — he was a Dunkin’ Donuts franchisee — that November.

“His life was his work,” Guttenberg said. “That final year I went back and forth to New York almost every week.”

Dr. Michael Guttenberg was given a hero’s funeral with full honors by the New York Fire Department. A procession of nearly 80 emergency service vehicles traveled down the Southern State Parkway, which was shut down for his funeral.

“I remember thinking I‘ll never be part of anything like this again,” Guttenberg said. “I was wrong.”

Again and again

Fred Guttenberg respected his brother, who had saved countless people, but was happy to return to his life in Florida. He was not an activist, not a public speaker, but a husband and a father. But he was about to be drawn into the maelstrom of gun violence in the United States and a kind of personal, slow motion 9/11 of his own.

Four months after Michael Guttenberg died, shots rang out on Valentine’s Day — a day that should have been a day to reflect on love, not loss. And for most of the nation, it was, but not at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School, named for a journalist and Suffragette, in Parkland, Fla., an affluent suburb about 30 miles northwest of Fort Lauderdale. Marjory Stoneman Douglas in a matter of minutes went from being a typical high school to a part of American history.

Seventeen people, including 14 students, were killed in that shooting, just shy of the 19 in Uvalde.

“I sent my kid to school on Feb. 14,” Guttenberg said. “The morning started off like any normal day in my house with two teenagers. They were running late. My dogs needed to be taken care of.”

He remembers that morning well, because it would be the last time he saw his daughter Jaime alive.

“I remember rushing them out the door. I don’t remember whether the last time I saw her I said, ‘I love you,’” he said. “I was sending my kids to school in Parkland, known as one of the safest communities in the country. I sent my children to school that day. Until about 2 o’clock that day, it was a perfectly normal day.”

That’s when his son Jesse called and said, “Dad, there’s a shooter in my school.” Guttenberg initially reacted with doubt and even disbelief.

“I said, ‘What are you talking about?’ he said.

“’No, I’m serious,” Jesse replied. “I can’t find Jaime.”

That was the moment of no return, a realization that the reality of gun violence had reached his family.

“As soon as he said he couldn’t find her, I knew he was serious,” Guttenberg said.

Blackboards and bullets

His son was running, hearing bullets: The shooting was in progress.

“The bullets he was hearing were coming from the third floor,” Guttenberg said. “They were the ones killing his sister.”

Like any proud father, Guttenberg carries photos of his daughter on his cell phone, but he reminds anyone who will listen that his daughter, and her death, are part of the present, not the past.

In the Hofstra Northwell lecture hall, he paused and played a video of Jaime dancing, silent amid music and what seemed like stardust dislodged from the edges of heaven.

“I want to introduce you to my daughter Jaime,” Guttenberg said, as his daughter, a competitive dancer, danced in the “Believe” national talent competition, enjoying life in a moment that this video would place in the eternal present “This is the beauty the world lost that day. This is Jaime.”

Jaime’s life ended in that shooting, but Guttenberg has been working ever since to make sure her legacy did not end that day. He has been fighting hard to remind people that each loss to gun violence is a huge loss, to show who she was and what was lost in a senseless second, that she is much more than a statistic.

“She was a tough-as-nails kid. She fought for other kids. She disliked bullies. Everything about her was good and decent,” Guttenberg said. “The reason I like to show you her dancing is to show you the reality behind these lives.”

Jaime still dances in that video, the picture of perfection and persistence, moving in a measured way, her whole life ahead of her, looking around before finally walking off stage in the video only to return the next time it is played.

“People talk about gunshot victims. That’s a gunshot victim,” Guttenberg said. “They were living and breathing and loving and being loved. And like that in a second it’s over.”

A quiet life

While the focus tends to go from shooting to shooting, it may be important to focus on those who are continuing to fight for change, after a shooting. Guttenberg comes from one of the most peaceful places: East Northport. Technically more south than east of Northport, East Northport is Northport’s neighbor.

“I grew up on an amazing block in East Northport,” he said. “Always outside, always playing. Safety and security were never things you worried about.”

There had been at least one horrifying moment in East Northport’s history, but that must have felt like a strange intrusion on a quiet life. And it is not an event forever emblazoned on East Northport’s identity.

On Aug. 11, 1989, Robert Kubecka, an FBI informant, and his brother-in-law Donald Barstow were murdered by Lucchese family members. For many people and many years, life has been largely peaceful, even pastoral overall in terms of that type of violence. Guttenberg grew up and attended Skidmore College, graduating as a business major, leaving New York at age 23 and moving to Florida.

“I loved the sunshine,” he said. “I was a single guy. I packed a car with what I could fit. And I never came back.”

He married Jennifer Bloom, a pediatric occupational therapist. They had two children and lived a fairly quiet life until gunshots shattered their lives.

“Gun violence can happen anywhere,” Guttenberg said. “I’ve traveled to communities in this country where gun violence happens. The majority is not in mass shootings. We do have an epidemic on our hands.”

In Jaime’s name

Guttenberg started a foundation in his daughter’s honor a few weeks after she was murdered and became part of a push for gun safety, the phrase he repeats, fighting on the linguistic front. It’s about safety, not just guns.

“My daughter’s favorite color was orange,” he said, wearing his ever-present orange ribbon and bracelet. “From the night she was killed, friends from the dance studio came over wearing orange ribbons.”

They made thousands of orange ribbons for attendees to wear at Jaime’s funeral. When someone at a supermarket asked Guttenberg what the ribbon was for, he learned he was closer than he realized to a cause.

“They said that’s the color of the gun safety movement,” Guttenberg said. “I didn’t know that. I just knew it was Jaime’s favorite color.”

After the shooting, Fred Guttenberg went from shock to speaking out. While many people retreat from the world after tragedy, he believed being silent would not serve his daughter’s memory or others well. She had been silenced; he would not. Her memory would not go away. She would not go away. He believed there was room for hope, compromise, safety and security.

“Following what happened in Parkland, I went through a process of finding my voice,” Guttenberg said.

The night after the shooting, he attended a vigil in Parkland, where he spoke before a crowd, something he hadn’t done before. Guttenberg then took part in a CNN town hall, giving an emotional speech that went viral. Emotion gave him energy.

“That was the night when it finally settled into my head,” he said. “My God, I was a victim of gun violence. I lost my daughter to gun violence.”

His daughter’s death, while personal, was part of something much bigger. He walked home and told his friends and family he would fight for gun safety, seeking to save lives. While this may sound like a small distinction, he was focusing on gun violence and not simply guns.

What had happened was both a moment and a movement. His brother had dealt with life and death; now he was, too.

“I set out on a mission since,” he said. “I want gun safety.”

Politics and Paralysis

Guttenberg sometimes has found himself caught in the middle of the debate, something he doesn’t want to happen. He traveled as the guest of House Majority Leader Nancy Pelosi (D-Calif.) in 2020 to then-President Donald Trump’s State of the Union. Guttenberg spoke out loud, clear and irately in a way that, he says, he regrets.

After President Trump said he would “always protect your Second Amendment right to bear arms,” Guttenberg shouted and was hustled out the door.

“I disrupted the State Of The Union and was detained because I let my emotions get the best of me,” Guttenberg tweeted at the time, adding that he wanted to be “able to deal with the reality of gun violence” and not have to “listen to the lies” about the Second Amendment.

He later said he needed to conduct himself “with dignity throughout this process and I will do better as I pursue gun safety.” Guttenberg seemed to say that his emotions, while they are engines behind his efforts, can stand in the way.

At that State of the Union, he struck out, but it did not advance his cause. Emotion is key in advancing, but it can get in the way. He was emotional recently as new federal gun safety legislation passed. It wasn’t the victory he wanted, but it was movement. It meant change is possible.

He cried, he has said, but this was a kind of limited relief. Something got done after decades of debate. Stagnation, for a moment, led to… something.

Gun safety debate

As Guttenberg sees it, a political debate has resulted in paralysis for decades when it comes to reducing deaths and injuries from guns. Still, he believes there has always been common ground, if people will simply listen to each other and look at guns as things that need safety measures.

It is not simply about whether people have guns, but the way, and when, they can get them; it is not about ideology, but about safety.

“I want gun safety,” he said of what he views as an approach different in principle and even in practice than what is perceived as gun control. “And there is a big difference.”

Guttenberg’s journey has led to encounters with many people, including politicians, ranging from a debate with Ted Cruz to support from legislators. The day he buried his daughter, he met Congressman Ted Deutsch.

“He helped to guide me through a policy process I know nothing about,” Guttenberg said. “He and his wife came to my house. He spent the night with us in our house. He said he was going to be with me and he has. He has been a hero ever since.”

Guttenberg said others such as former Ohio Gov. John Kasich and then-Vice President Joe Biden consoled him and his family.

“He talked to me about getting through grief, mission and purpose, using my voice, about what to expect, about how grief is unpredictable,” Guttenberg said of Biden. “We don’t all grieve the same way.”

Guttenberg believes in persistence as paving the pathway to change.

“After what happened to my brother and daughter, my religious faith has been shattered,” Guttenberg said. “But my faith is stronger than ever in the people I get to know every day.”

Surviving a shooting

Guttenberg, whose daughter was 14 when she died, has a son, Jesse, who survived the shooting. Shootings not only leave victims, but survivors who seek strength of their own. Guttenberg says he has a lot of respect for how so many young people handle themselves.

“I’ve watched the teenagers around me live on their cell phones. I thought kids were growing up not knowing how to communicate and I was wrong,” Guttenberg told the med students at the Hofstra-Northwell School of Medicine. “Not only do you know how to use your voices. I’m finding that people your age are fierce about what you want and stating what you want.”

He has watched Parkland students, and now graduates, push for gun safety, rather than letting it fall by the wayside as shootings too easily can turn into statistics rather than safety measures. And he seemed to see the Hofstra-Northwell students, and young people in general, as hope.

“The cell phone used by people your age helps you coordinate, connect and deliver messages in a way we adults were not able to,” Guttenberg said.

One reason that Guttenberg has had hope over the years is that change has occurred, despite the paralysis of many politicians. He has been part of successes, long before the recent legislation.

After the Parkland mass shooting, Florida passed a package of laws designed to reduce gun violence. The community and the state seized the moment rather than simply moving on to the next.

Three weeks after the Parkland shooting, Florida passed gun safety legislation known as the Marjorie Stoneman Douglas High School Safety Act, providing additional funding for school safety and security, as well as raising the age to buy a gun to 21 and adding a mandatory three-day waiting period. Despite often anti-regulation rhetoric from many Florida politicians, this legislation, energized by emotion and tragedy, passed.

“It’s Florida and it was a big step,” Guttenberg said. “A horrific event happened. Myself and the other families, we mobilized immediately and we marched to Tallahassee. It was a moment in time. Everybody felt the pressure to do something.”

The laws were passed in a state where another mass shooting had occurred just before that, without leading to change. The double punch may have helped set the scene for action.

“A year before that was Pulse and they did nothing. I think they were still stunned by having done nothing after Pulse,” Guttenberg said. “What we did in Florida shows how gun safety does not affect legal, lawful gun owners. There’s not a legal, lawful gun owner affected by any of the legislation passed in Florida or other states.”

Jaime’s law

Guttenberg has been working to get federal legislators to introduce and pass Jaime’s Law, which focuses on ammunition. While he spoke to med school students on Long Island, he also tries to win over support in Washington, D.C.

“If you are a prohibited purchaser of firearms, then you are prohibited from purchasing ammunition,” he said. “We want to extend background checks to ammunition.”

There are more than 300 million guns in the United States, but Guttenberg believes ammunition should be treated equally seriously. People who obtain guns illegally can all too easily buy bullets, he believes.

“You already have the weapons on the street. They are already there,” he said. “Those who are going to use them may be prohibited purchasers or may be too young or have a history of violence. They walk into a store and buy the bullets. There’s no requirement for a background check on bullets.”

As Guttenberg sees it, ammunition may be far too readily available – even for people not permitted to have guns.

“Ammunition to me is going to be the most effective gun safety measure once we get it done,” he said. “It’s the only thing out there that deals with the reality of the guns that already exist.”

Although the federal government has done little for decades, even ending the assault weapons ban, Guttenberg hasn’t given up or remained fixated only on federal legislation.

While working to get the federal government to take action, Guttenberg met with Pennsylvania Attorney General Josh Shapiro.

“I started working with the states,” Guttenberg said. “He put together a coalition of 21 attorney generals who wrote a letter to the House and Senate leadership, saying why they support Jaime’s law.”

Ammunition is part of the answer

California already has passed ammunition background checks followed by states such as New York, New Jersey, Connecticut, Illinois and Massachusetts.

Guttenberg has had ups and downs, successes and struggles, seeking to push for gun safety. There have been disappointments, broken promises and abrupt changes in direction and the U.S. Supreme Court recently struck down bans on the right to openly carry firearms. But Guttenberg says no other disappointment comes close to the day he lost his daughter.

“I’ve been unemployed, didn’t know how to pay the bills, been a business owner with the highs and lows of that, an employee with the highs and lows of that. I lost my brother to cancer,” he says. “Then I lost my daughter to gun violence. Nothing comes close.”

He lost his daughter and found a cause at the same time, dedicating his life to measures that he believes can save lives and keep Jaime’s name and memory alive, even as he looks at the video of his daughter dancing on a screen.

He would like to see the age for buying firearms raised to 21 and would like legislators to “look at ways to handle ammunition.” And those are just a few things that he believes could help and battle shootings like the one that took his daughter’s life.

“There’s so much more we can do to save lives without doing anything to affect anyone’s Second Amendment rights,” he said recently on MSNBC.

Northwell Health, meanwhile, founded a Center for Gun Violence Prevention, where last month other families who lost loved ones to gun violence, spoke out. Shenee Johnson, of Shirley, said her finance, cousin and 17-year-old son Kedrick Morrow all died of gun violence.

“Our stories did not make national news,” she said recently. “But as a Black woman in America, I’ve had to bury three people all killed by illegal guns. I’ve dedicated my life to be their voices.”

Gun deaths often create gun safety advocates, yet change is difficult even when measures are what many would consider “common sense.” There is a kind of community of loss, a solidarity among those who lost loved ones, yet each family member is on their individual journey as well. Amid progress, there are additional losses, both through shootings and legislation, such as the Supreme Court ruling striking down New York State’s open carry regulations.

Things aren’t getting easier for those pushing for change. Still, Guttenberg believes the world is full of heroes, including his brother and others who helped on 9/11. Chesley Sullenberger, who landed a plane on the Hudson, is another example of courage. And he believes change is both possible and necessary. Jaime had dreams. Fred Guttenberg does as well.

“Focus not on the moment, but how you react to your moment. That will define what happens to you afterwards,” Guttenberg said. “My daughter had a saying. She didn’t write it, but she lived her life by it. ‘Dreams and dedication are a powerful combination.’ I have a dream. I’m going to dedicate the rest of my life to reducing the gun violence in this country.”