La Amistad: How the U.S.’s First Civil Rights Case Sparked in Montauk

In English, the Spanish name of the sailing ship meant “friendship.” It also meant “companionship.” “Comradeship.” “Fellowship.” “Camaraderie.”

But those meanings meant nothing to the slave hunters who abducted 53 young men and children from their home in West Africa, packed them onto a crowded ship, and transported them across the Atlantic Ocean in 1839. En route, the slaves staged a bloody rebellion. When the schooner landed east of Montauk Point, a U.S. Navy brig seized the ship.

Even though the federal government banned the transatlantic slave trade in 1808 and slavery had been abolished and ruled illegal in New York State since 1827, the kidnappers were set free, as slavery was not outlawed in the U.S. until 1865. The African mutineers were imprisoned and charged with murder.

La Amistad’s captives could not know that their uprising would change the course of Black history — and become the subject of what many call the first civil rights case in the United States.

VIOLENT VOYAGE

Some historians say the ordeal began in January or February 1839; others have written that it was in the spring that Portuguese traders violated all existing treaties and kidnapped hundreds of Mende tribespeople from their native land in present-day Sierra Leone in West Africa.

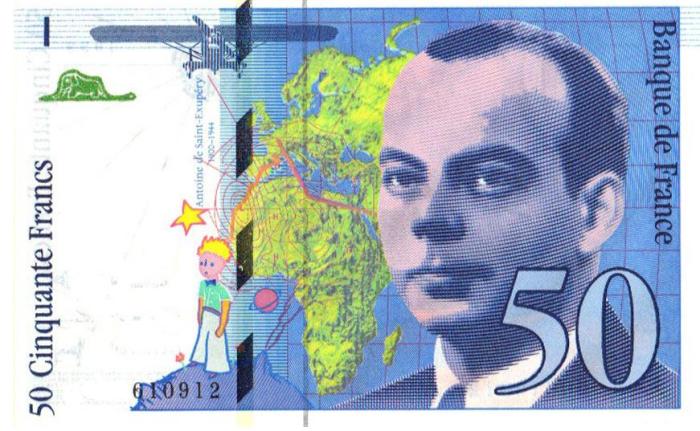

An account by the Cambridge University Press describes how Black captives were illegally transported to Spanish-ruled Havana, Cuba, a major hub of slave trade, even though the importing of slaves had been banned in the Spanish colony; the kidnappers skirted the law with fake documents that said the West Africans were native Cuban slaves. The captors then sold 49 men and four children — three girls and a boy — at auction, to two Spanish plantation owners, who locked them in chains on the Amistad, bound for a Caribbean plantation.

One of the enchained men was a rice farmer and trader named Sengbe Pieh (later called Joseph Cinque by Spanish slave traders). He had a wife and three children and had been working in the rice fields when he was forced into captivity.

On board the 64-foot-long Amistad, crammed full of cargo and humanity — 60 people were crowded onto its 1,200-square-foot deck — the shackled prisoners endured rough seas and sickening conditions. They were nearly starved to death. The white captain and crew whipped, clubbed, and punched them.

On July 1, 1839, Pieh broke free, freed the other captives, and led a bloody revolt. From the account by the Cambridge University Press: “They used a moonless night to launch a surprise guerrilla attack (in Mende, Kpindi-go), using war shouts and swinging their blades wildly.”

The prisoners killed the ship’s captain and the cook and a number of the captives were slain. The surviving West Africans ordered the plantation owners to sail the Amistad back to their homeland. But their kidnappers secretly steered the ship north to the United States in hopes of being intercepted.

For nearly two months, La Amistad was lost; 10 of the Africans died of starvation or illness. The ship came aground and was lying at anchor at Culloden Point near the north shore of Montauk, about three-quarters of a mile off the Long Island shore, when the U.S.S. Washington seized it in late August. Searching for water and provisions, Pieh and the other prisoners came ashore, but private citizens caught them.

The Amistad was towed to New London, Connecticut — slavery was technically legal there — and the plantation owners were freed, despite their having transported the prisoners illegally.

AFRICAN INMATES

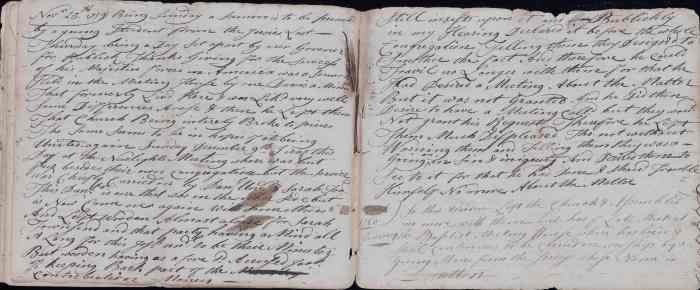

The surviving 43 Africans were charged with mutiny and murder and imprisoned in a New Haven jailhouse. For nearly two years, even the children, “three girls and one boy,” were detained “in a room by themselves” at New Haven, wrote abolitionist Joshua Leavitt after visiting the prisoners, according to the William G. Pomeroy Historic Roadside Marker Program website.

The kidnapping victims remained in jail despite some of the charges being dropped, as the case worked its way to the U.S. Supreme Court. The Africans formed an alliance with abolitionists, people who sought to abolish slavery and work for the full emancipation of enslaved people.

The U.S. National Archives and Records Administration relates how abolitionists hired attorneys to convey the Africans’ position; the attorneys wrote: “ …Each of them are natives of Africa and were born free, and ever since have been and still of right are and ought to be free and not slaves…” Additionally, while suffering “great cruelty and oppression,” the Africans were “incited by the love of liberty natural to all men” to take possession of the ship by force and seek asylum somewhere under governmental protection where slavery did not exist.

In March 1841, the Supreme Court ordered the 35 Africans who were still alive to be freed. They set sail for Africa in November, arriving in January 1842; the journey to their homeland was paid for with funds raised by abolitionists.

Today, the Amistad Memorial historical marker stands on Montauk Highway near the Montauk Point State Park lighthouse. Its inscription reads:

July 1839, Joseph Cinque, leader of Mende

Captives from Sierra Leone, overpowered the crew

of the slave ship La Amistad off Cuba and landed

at Culloden Point, Long Island. Captured and

tried in a New Haven Court, the Africans were

later defended by John Quincy Adams before the

U.S. Supreme Court and set free to return to their

homeland.

Dedicated by

the Eastville Community Historical Society

of Sag Harbor

August 1998

Related Story: 5 Powerful Stories of Black History on Long Island