Louisine Havemeyer: Long Island Suffragist Made Women’s History

She was a 63-year-old grandmother who picketed the White House with banners and signs as fellow protestors burned an effigy of President Woodrow Wilson. She was attacked by counter-protestors, arrested, and jailed. But she was nothing if not determined, and so she persisted.

Sound like current political protests? This divide actually tore the nation apart in the early 1900s as women and men alike took sides over the political football of the day: women’s rights.

When not leading demonstrators, suffragist speaker and activist Louisine Waldron Elder Havemeyer retreated to her Islip and Commack homes on Long Island to strategize how to bring about equal social opportunities and protection for women under the law.

RELUCTANT BUT RESOLUTE

From early on, Louisine Waldron Elder had advantages not given to many. Born into a wealthy New York City family in 1855, when she was just 19 the socialite traveled with her family to Europe and was introduced to American painter Mary Cassatt.

Their meeting in Paris would lead to a close friendship: Elder was impressed by Cassatt’s self-reliance and passion for painting, which inspired Elder to start collecting art. The first American to seriously collect French Impressionism, Elder purchased works by Manet, Monet, Cezanne, Renoir, and Cassatt.

Nine years later, Elder married Henry (“Harry”) O. Havemeyer, an American industrialist who amassed a fortune running a lucrative sugar business in Brooklyn. Nicknamed the “Sugar King,” the millionaire was also an avid art collector.

While the couple owned property in Rhode Island, Connecticut, and Suffolk County, home base was their Fifth Avenue Manhattan mansion, designed by Louis Comfort Tiffany. Their summer residence would be Islip. Construction on the 10 houses at Bayberry Point, a cape on the Great South Bay, was begun in 1899. According to the Historical Society of Islip Hamlet Historical Markers website, by spring 1901, Havemeyer and his family were ready to move into their new home.

The businessman also established the Merrivale Stock Farm in Commack, where he owned a modest stone house and acreage; he died there in 1907. Reacting to the death of her husband and other family members, his grieving widow attempted suicide.

“I lifted the torch as high as I could and for once I did not have to think – the words came to me as if by inspiration,” wrote Louisine Havemeyer.

In 1914, as World War I ignited, she heeded the advice of her friend Cassatt to focus on suffrage, the right of women by law to vote in national or local elections. That right had been denied worldwide dating back to ancient Greece and republican Rome, where women were excluded from voting, according to Britannica.com.

Havemeyer’s mother had been interested in suffrage and was friendly with pioneers in the movement, which no doubt influenced Louisine’s desire for social change. Cassatt urged her friend “Louie” to “work for the suffrage. If the world is to be saved, it will be the women who save it.”

The wealthy widow held regular meetings at her mansions and used her late husband’s considerable resources to help support the suffragists with financing, and in 1915, she organized the “Exhibition for Suffrage Cause” fundraiser featuring works by Degas and Cassatt. She evolved to become an effective speaker, even addressing an audience at Carnegie Hall. As author Elaine Weiss was quoted saying in the New York Times, “She doesn’t just write the check, but is out there on the barricade.”

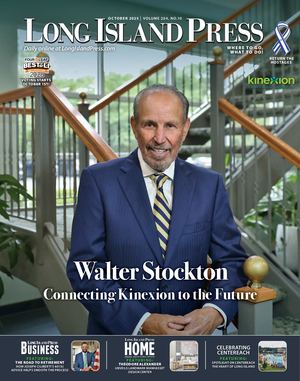

Havemeyer held the “Torch of Liberty” sculpture as she gave speeches for the cause. At first she was reluctant to be photographed holding the wooden bronze-finished torch. But as she later wrote in “The Suffrage Torch” in Scribner’s Magazine, “I lifted the torch as high as I could and for once I did not have to think – the words came to me as if by inspiration.”

AS CALM AS CROQUET

By 1917, suffragists were exposing the hypocrisy of the war effort and “how the United States could be fighting to make the world safe for democracy when not all Americans could vote,” The New York Times reported. Havemeyer and other “suffs” continued to pressure legislators; The Times described her as “an ardent feminist who would jazz up her speeches … with a battery-powered model of the Mayflower that would suddenly light up when she came to the part about women finally winning the vote.”

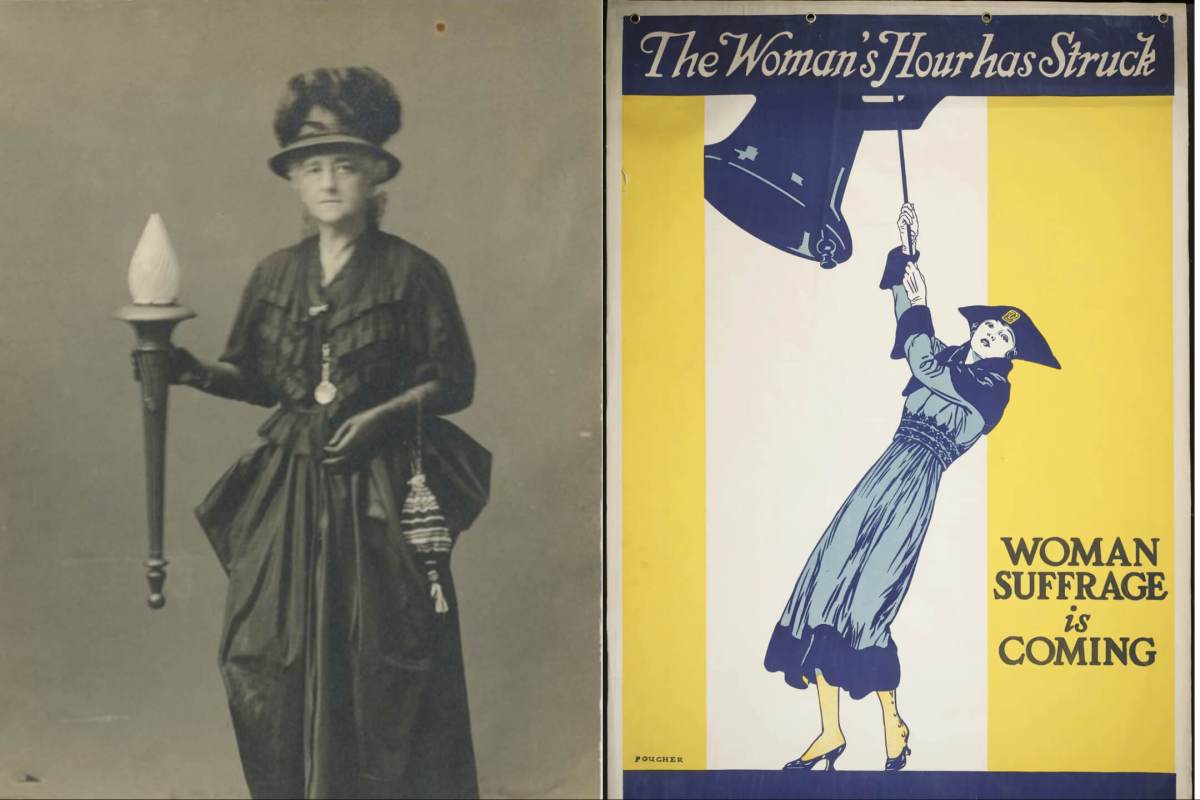

In November 1917, Havemeyer led the New York delegation of “Silent Sentinels” — protestors who held their tongues while holding banners — who wore purple, white and gold sashes as members of the National Woman’s Party.

The first group to ever picket the White House, they burned an effigy of President Wilson and were attacked by angry mobs. Havemeyer and some 30 other picketers were arrested, imprisoned, and tortured during what was later named the “Night of Terror.” She refused to pay the $5 fine so the elite pillar of society spent three days in jail.

She later said that during the protest she felt “as placid and calm as if I were going out to play croquet on a summer afternoon,” reported the New York Times.

The 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which gave women the right to vote, was ratified in 1920. Havemeyer died nine years later.

Related Story: 7 Trailblazing Long Island Women Who Made History