By Jennifer Corr

jcorr@antonnews.com

Syosset author Sherwin Gluck didn’t know much about his father, Irving Gluck, growing up. It was later he would learn the story of his father, a once teenage Jewish immigrant turned American infantryman during World War Two.

“There were only a few things that pointed in directions that something was different,” Gluck reflected. “On the Fourth of July, my dad didn’t like fireworks. We would go to my grandmother’s home on the South Shore, to Fireman’s Field. And, he did not want to be there. He was nervous, and that was of course from his combat experience. At night, sometimes he would wake up and you’d hear him screaming. It was not discussed, and in terms of the Holocaust, the only thing we were told was that my uncle had been hurt with an ax and he had an infection in his foot and he died. So I think they were trying to shield us from it.”

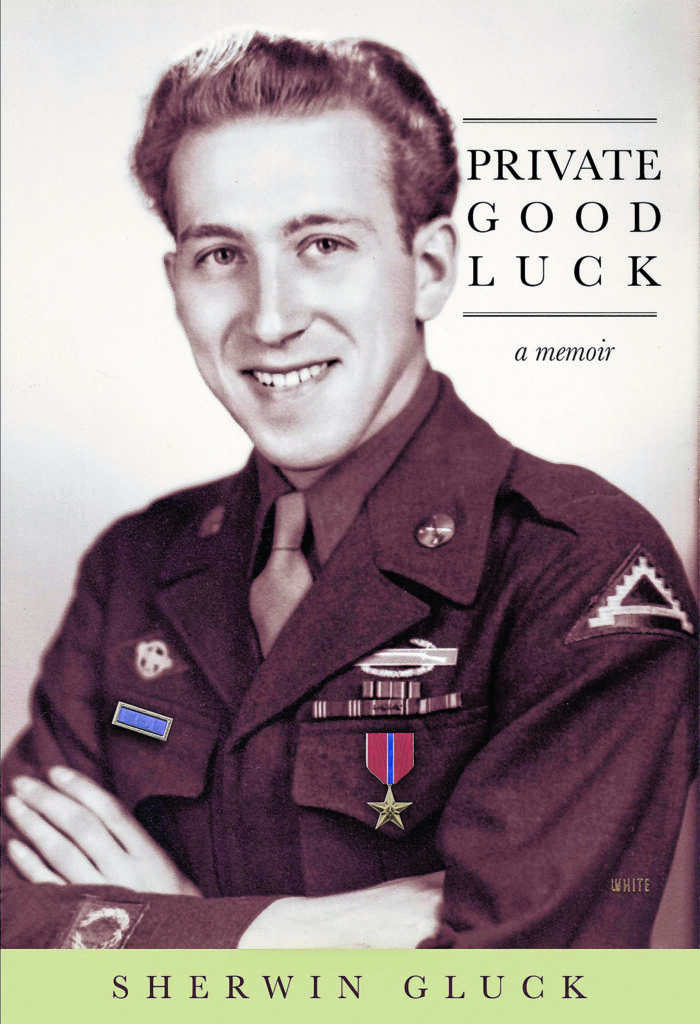

He would become the subject of Gluck’s book, Private Good Luck, which has been used the past three years as part of South Woods Middle School and H.B. Thompson Middle School social studies curriculum.

Teaching the Holocaust is a long-standing component of the eighth grade social studies curriculum at the Syosset Central School District.

“His book, Private Good Luck is a poignant account of how hatred, ignorance, and indifference impacted his family during World War II,” said Stephanie Russell, South Woods English Teacher and DASA Coordinator. “The stories he shares stem from intolerance and ignorance. His father’s painful experience with prejudice as well as his conviction to take a stand against the hate and injustice that destroyed so many lives provides an opportunity for us to reflect on the prejudice and hate in our own world and how we respond today.”

Gluck’s father did speak to classrooms at local schools about his military service, but not about his family. His father would share one aspect of his younger life, the village he grew up in: Polyán, Czechoslovakia.

“He didn’t really know much about what the facts were about their existence and their ultimate murder,” Gluck said.

It was until the early 2000s’ when thousands of records from the Nazis became public, that Gluck’s family was able to send a request to see what had happened to their family. They found out about his father’s oldest brother and when he was taken, what was confiscated from him, when he arrived to Auschwitz, when he was transferred from Auschwitz to the Mauthausen, and they could see his daily work logs.

“Now, all of a sudden, the story we were told was very clear,” Gluck said. “The story was not that he hurt his foot and got an infection and died. We understood very clearly what my dad had only guessed.”

In 1999 or 2000, Gluck sat down with his father and interviewed him about all his experiences.

“It was about leaving Europe, and what his experience was coming to America,” Gluck said. “Trying to learn English, trying to fit in, and then once Pearl Harbor happened and the United States entered into the war, his registering for the draft as an alien and eventually being drafted and going into basic training, his combat experience, coming home and what that was like and then how he adapted to being a civilian again and getting a job, and an education. He had a box from the military that had a few items, memorabilia in it. But at that point, he started going through these letters.”

It was those letters that would inspire Gluck to create Pappus: The Saga of a Jewish Family, a compilation of the letters translated to English released in 2021.

The letters were also sent to the United States Holocaust Memorial and Museum in Washington, D.C., which will be published online as part of a growing database of records.

When Gluck’s father found the letters, he gave them to his older sister Marie, who was looking for something to do. She went through the letters and organized them into albums, keeping the thin air mail paper safe.

“She would find some of the letters she had written herself, and my dad had written, and she would show them to my dad,” Gluck said. “These letters, a lot of them were in Hungarian. And my dad would translate on the fly. And you could see he’s getting upset by it because it’s from his father, his sister, or brother, reminding him.”

The letters, written during the day of World War Two, created a bigger picture of what this family had been going through, including the struggle of immigrating to the United States. “You’re getting monthly letters, monthly reports,” Gluck said. “What’s happening. How they’re trying to get the passport, why they can’t get the passport. The regular going-ons of their village, who’s getting married, who died. All the details happening in their life, not knowing what’s going to happen… You see how the time was changing how the letters evolved… It’s very powerful to see.”

To purchase Private Good Luck or Pappus: The Saga of a Jewish Family, search for the book titles on Amazon.