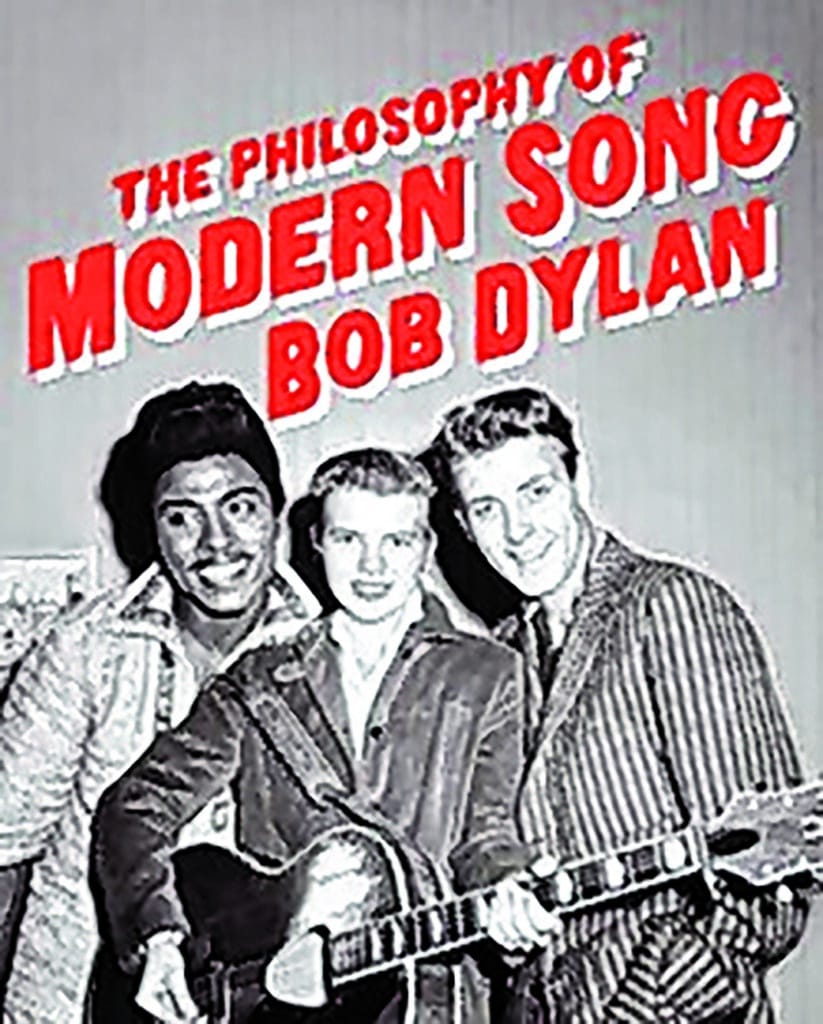

Can rock stars write good books? I don’t mean ghost-written efforts. There was Dylan’s own Chronicles, a two-volume book that lurched from one drab sentence to another. Add to that George Harrison’s I, Me, Mine, another tome badly in need of a blue pencil and Bruce Springsteen’s Born To Run, colorful but overwrought in the man’s belief that rock music remains a temple his fans come to worship in. (They just want to hear “Rosalita.”)

These books generally announce to the world that Dylan, Harrison, and Springsteen were great songwriters.

This one is different. Bob Dylan spent 10 years on The Philosophy of Modern Song. It works, in part because Dylan knows these tunes front and back. Plus, he took his time writing its chapters. Dylan lets his imagination run free, but controls it in short, succinct essays. The music is transcendental. The entire song is, like poetry, an experience, rather than a puzzle. Consider his analysis of Bobby Darin’s “Beyond The Sea.”

“Soon the fair winds blow you into the harbor and you see the port lights. Soon you’ll be approaching and coming up. You’ll hit town and weigh anchor, and she’s sanding on the shores of everlasting gold. Soon you’ll be shut off from the world, linked up everlasting. On top of each other, you’ll kiss and embrace, every day from now, a jolly holiday. Wonderfully brilliant and true to form. You see everything from the proper angle, you’ve returned to where you came from. No more casting off into a distant galaxy. No more cruising off into supernatural darkness. Never again you’ll go sailing, you lay it all down and pull the shade. You quit while you’re ahead.No collection of American music would be complete without Hank Williams, Sr. Dylan celebrates his mournful classic, “Your Cheatin’ Heart.”

Soon you’ll be marching on the same side of the road as what I’m on, we’ll see how you handle that. You were prejudiced, stupid and hypocritical, and now your cheatin’ heart is making its presence felt. You didn’t want me to live an honest life, you bamboozled me and ripped me off, and now there’ll be no more sleep for you. Not this night, not any night. You thought you could do anything, thought you’d live forever, and you gave it all you had. You just didn’t have the right character to pull it off. It’s a hell of a thing, isn’t it.The title of this review is lifted from Dylan’s fifth album, a 1965 effort that was one side acoustic, the other side rock n’ roll. As a youngster growing up in Hibbing, MN, Dylan (back then, his real name Robert Zimmerman), spent his nights listening to music stations from across the land. The Fifties, contrary to being a dull decade of conformity, was in fact a highly creative and eclectic period. Dylan soaked it all in: country, folk, rock, jazz, blues, swing, big band. As with every other brash Fifties kid, Dylan was a young Elvis. By the early 1960’s, rock’s initial phase had petered out. Folk music was in vogue, especially on college campuses. Dylan had a new idol, Woody Guthrie. The latter had a house in Queens County. Dylan made the pilgrimage. More important, he took on and conquered the Greenwich Village folk scene.

This volume is really Bob Dylan’s Great American Songbook. The man clearly reveres his masters and mentors. These men are not entertainers, they are teachers. Dylan’s own status, plus his reverence puts him on a first name basis with “Frank,” “Dino,” “Tony,” “Bobby,” “Dion,” “Rickey,” “Willie,” “Hank,” “Ella,” “Billie,” and especially “Johnny.” If Dylan had a soulmate in contemporary music, it would have to be Johnny Cash. When Dylan made the plunge from folkie to rocker, Cash stood with him all the way. “Shut up and let him sing!” the Man in Black declared. Johnny Cash was just the friend Dylan needed at that point in his career.

As with any collection, there are omissions: Songs by The Who and The Clash, but no Lennon and McCartney, Springsteen, or Neil Young ballads. The reader will discover and delight in the greatness of American music in all its variegated forms. The authenticity of these tunes, some famous, others forgotten, shines through on every page.

The book opens with a photo of the young Elvis Presley, decked out in white shoes (don’t step on them!), followed by a scene in an Anywhere, U.S.A. record store to finally, a photo of the immortal Johnny Ray belting out a tearjerker. Johnny? Yes, Cash, but Mr. Ray, too.

Can’t forget him.