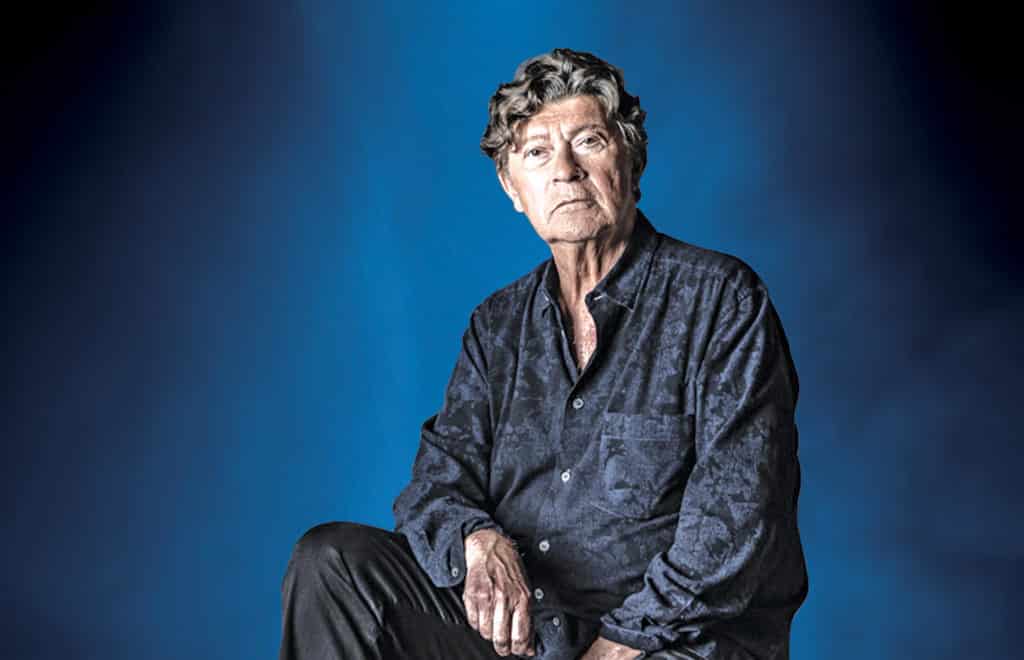

New documentary tells his story of The Band

Robbie Robertson has had quite the full dance card in the past seven months. Back in September, he released Sinematic, his sixth solo release, which featured contributions from Derek Trucks, Citizen Cope and Glen Hansard from the Irish group The Frames and his first set of original material since 2011’s How To Become Clairvoyant. This preceded the score he composed for friend Marty Scorsese’s Oscar-nominated mob film The Irishman in November. Currently, Robertson has been making the rounds promoting the recently wide-released Once Were Brothers: Robbie Robertson and the Band, a Canadian documentary based on the Rock and Roll Hall of Famer’s 2016 memoir, Testimony. For Robertson, he’s been admittedly been riding quite a wave of creative activity.

“This has all been so rewarding at this stage of my journey and this age—it’s been one of the busiest years of my life,” he said.

Helmed by 24-year-old director Daniel Roher, Once Were Brothers got its start when a number of parties approached Robertson about adapting his autobiography into a film. The company that wound up with the job was White Pine Pictures, a Canadian film company that had produced a number projects including a documentary on late classical music composer Glenn Gould that Robertson had seen and admired. Before long, Brian Grazer and Ron Howard’s Imagine Documentaries came on board and Scorsese offered to hop on board as an executive producer. And while Robertson got some push-back on the young age of the film’s director, he had faith in Roher. Those later aforementioned developments confirmed Robertson’s gut instinct about the direction Once Were Brothers was headed in.

“When Daniel Roher came along and said it was his wish to do a documentary based on Testimony, I checked him out, got a good feeling about it and said we should go with this guy,” Robertson said. “At first, everybody else that was involved with it said he was 24 years old and they wanted to know what he was going to do with this [project]. They didn’t think he knew about his period of time or my story. So I said that I just had a feeling and I just wanted to try it. So anyway, he was so dedicated and involved and did a great job digging deep in finding the material and everything. It evolved into another place. Imagine Pictures came into it and then Martin Scorsese saw a rough cut of it and said he thought it was really going to be good and asked if I wanted him to help out and that he’d be happy to do that. So we were like, ‘Whoa, we’re getting somewhere.’”

The film itself is a chronological ride that incorporates archival film and audio footage from the other members of The Band (Garth Hudson is the only surviving member. Richard Manuel passed away in 1986, Rick Danko in 1999 and Levon Helm in 2012). While the presence of high-profile talking heads like Scorsese, Bob Dylan, George Harrison and Eric Clapton given the film a bit of a hagiographic tinge, it’s hard to argue when taking in the considerable impact of The Band. In addition to laying the groundwork for what became the Americana music decades before it even came into existence, these four Canadians and an American were accomplices in helping Dylan go electric, a controversial move from someone who had become a folk music icon and was treated like a heretic when he started plugging in with help from The Band. Such was their influence that Clapton, who had made a name for himself as a guitar god via his work in the Cream power trio, sought out the Band in Woodstock in the hopes of trying to join their ranks.

While The Band’s original lineup shot the 1976 documentary The Last Waltz as a means of bidding farewell to touring after being on the road together for 15 years, the group sans Robertson regrouped in 1983 and soldiered on for another 16 years, releasing three more studio albums and finally breaking up following Danko’s 1999 death.

In the aftermath of The Last Waltz, the deteriorating relations between Robertson and Helm became more acrimonious, with the latter accusing his bandmate of commandeering the finances and direction of the group, which were addressed in This Wheel’s On Fire: Levon Helm and the Story of The Band, Helm’s 1993 autobiography penned with help from noted author Stephen Davis. And while detractors have not only spent years accusing Robertson of being self-aggrandizing, the tone of both his memoir and the recent documentary is one that involves a lot of shared credit and delight about the group’s adventures, along with a degree of sadness when times turned dark via the rock star tropes of drug abuse and bad behavior. It’s something Robertson readily admits he saw in both the writing of his book and creation of the film.

“I found sadness in places,” he said. “I found much more joy and much [incredulousness] looking at what we went through. The fact that I’m still alive [is something]. There was some very dangerous things in our experiences—playing the chitlin’ circuit down south. Hanging out with all these gangsters, thieves and underworld characters. It was just part of our world. No matter where we were—it just seemed like we connected directly with the underworld.”

While Roher included what appeared to be newer archival interview footage with Helm, the criticism of Hudson apparently being MIA has been brought up by some critics who have seen the film. When asked about that, Robertson said Roher did track his former bandmate down, but came away empty.

“[Daniel] worked really hard and was very determined to have Garth involved,” Robertson recounted. “He tried on different occasions, went to Woodstock and it was set up to do something with Garth, but it didn’t work out. He kept pushing for it and pushing for it and then he went back and met with Garth. I’m trying to be delicate about this—he tried to shoot some stuff with Garth and it didn’t work. Daniel felt bad. He didn’t want anything that didn’t make Garth look good. And Daniel thought his number one responsibility was respect for me and the guys in The Band. And he said—Garth had some things he’s dealing with. It wasn’t for lack of trying. I would have loved for Garth to be in there. Garth is so dear to me. Daniel said he did his best, but they couldn’t make it work.”

With the different projects Robertson was working on simultaneously, the creative flow came together to influence what became Sinematic. This inspiration got to the point where Robertson painted different, often violent images, to go with each song in the packaging.

“I started out just thinking that I had some ideas for some songs, like you always do,” he said. “But then, when I stepped inside the zone for doing this, I was also beginning to work on The Irishman. Then, they were starting to work on this documentary. What happened, which has never happened to me before, was that all these things were starting blending together and I was getting off on it. I just had one of the greatest musical journeys that I ever experienced making this record, because all of these pieces connected. I was writing about things from the early days that I remember. And because I’m writing Volume II of my memoir.”

An avowed cinephile, expect plenty more from Robertson as we get deeper into 2020.

“I really have to dig in on Volume II of this memoir,” Robertson said. “I’m just finishing up a piece of music that Eric Clapton and I did together that is so cool and I am going to start working on Martin Scorsese’s next film—Killers of the Flower Moon. And there is a ton of other things lurking around. I’ve got a feeling that it’s going to keep me out of trouble.”

Also read about Robbie Robertson’s favorite filmmakers.

https://liweekly.wpengine.com/robbie-robertson-cinephile/