This year, the “threes” have it. 1923. The year Yankee Stadium opened. The year of the legendary Jack Dempsey-Luis Firpo fight took place. (There will be more of the latter in a coming issue.) In 1923, Calvin Coolidge, former governor of Massachusetts, became president of the United States.

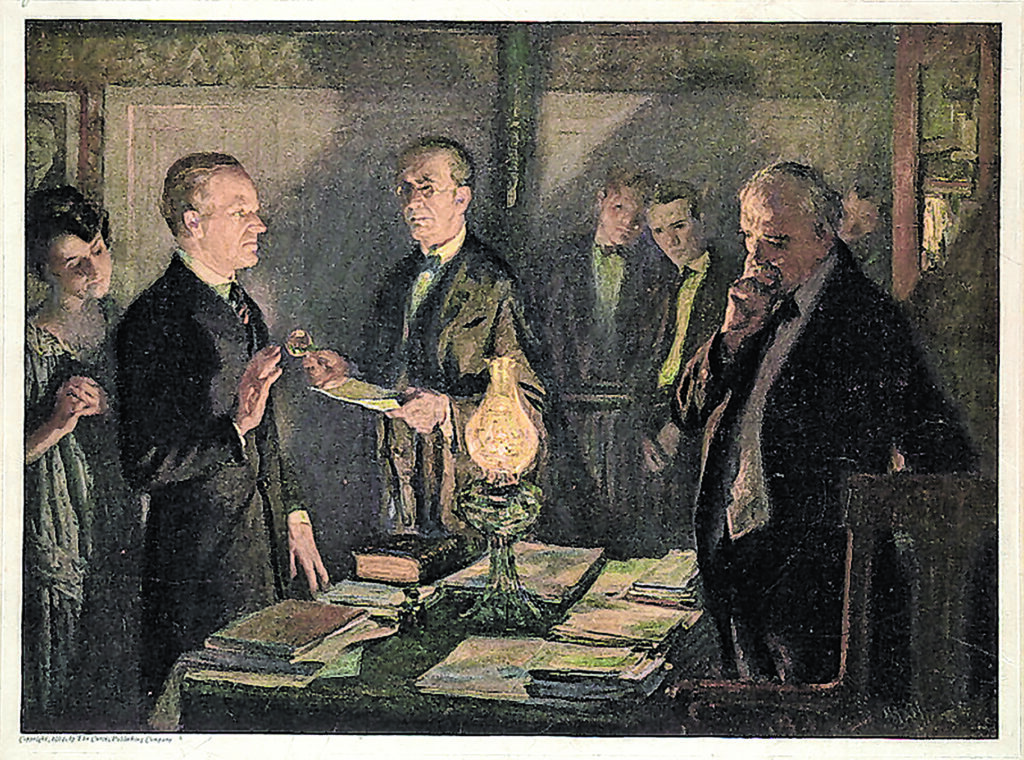

On Aug. 2, 1923, Vice President Calvin Coolidge was sleeping at his retreat in Vermont. President Warren Harding, who had been suffering from ill health, had died. His passing was not a surprise. Coolidge was now president. His father, a notary public, issued the oath of office to his son.

When asked about his daunting responsibilities, Coolidge reportedly replied, “I can swing it.” This was a man of few words. Five years later, when the man decided to forego a 1928 re-election bid, he issued a terse press release. “I have declined to seek re-election.”

In between, Coolidge gave America the best five years any nation could ever have. More to the point, Coolidge continued Harding’s legacy. Running, in 1920, on an America First platform, the Harding-Coolidge ticket took an easy victory. At the time of his death, Harding was highly popular. If he had lived, Harding would have won re-election in 1924 and be remembered today as a top-tier president.

Today, Harding is pretty much forgotten, an embarrassment, due to such scandals as the Teapot Dome, where government contracts for oil exploration ended up with friends and cronies.

Coolidge, however, has enjoyed a minor revival. A biography by Amity Schales remains popular among conservatives. The Calvin Coolidge Foundation, chaired by Schales, has been established.

Some of this is surprising. The conservatism that is taking a second look at Coolidge has been pro-interventionist, pro-immigration, and pro-free trade. It was a George Bush party. Coolidge was the exact opposite of today’s Republicans on those nation-defining issues.

Calvin Coolidge was the right man at the right place. With World War I over, Americans settled back to enjoy a brief Age of Normalcy. It was a loud age, too. Flappers, stock jobbers, the Charleston, jazz, radio, “the talkies” at the movies. And the sports stars: Babe Ruth, Bobby Jones, Bill Tilden, Red Grange, Jack Dempsey. And the movie stars: John Barrymore, Mary Pickford, Rudolph Valentino, and Gloria Swanson.

Harding was a charismatic man himself. Coolidge, however, seemed more representative. Let America party on. The president would attend to his constitutional duties and leave local government up to local municipalities. The only contact Americans had with the federal government was the local post office.

By the 1920s, Americans were also paying an income. Neither Harding nor Coolidge could repeal that 1912 piece of legislation. The man had his successes. They don’t call it The Roaring 20s for nothing. As Pat Buchanan in The Great Betrayal:

Having pledged to “prosper America First,” Harding and Coolidge were true to their word. America took off in her new Stutz Bearcat on the wildest ride in history. The results were startling. Unemployment, which stood at 12 percent when Harding took office, was down to 3 percent when Coolidge went home…No president of the twentieth century did better at reducing the “misery index” than the maligned Harding; and when Coolidge said good-bye to Washington in 1929, the U.S. share of world manufacturing had reached a record-shattering 42.2 percent. Harding and Coolidge had proved another historic point: lower tax rates need not reduce tax revenue. As the top income tax rate plummeted from 73 percent to 25 percent, income tax revenue grew in five years from $690 million to $711 million.

Under Coolidge, America First soldiered in. In 1920, Harding campaigned on immigration restrictions. In 1921, a Republican congress reduced legal immigration. Three years later, in a presidential year, the GOP cut it further to a 100,000 immigrants per year, down from 1,000,000 just five years earlier. Coolidge kept America out of war. With World War I, Americans were tired of wars to keep the world safe for democracy or for that matter, wars to expand democracy. Coolidge’s America was not a welfare state. There was no big government for people to rail against. Government was small enough to remain efficient. Or as Chris Stirewalt has observed:

Coolidge, quietly, deliberately, carefully cleaned up the government. His modesty and decency proved to be the balm that the nation needed at a time of political and social unrest. His good sense and good character kept his administration out of trouble, and finally provided the stability the nation had sought since the upheavals of the Great War. He fulfilled the Founders’ vision of executive leadership at a time when institutions were breaking down.

No political operator could have drawn up the plan for Coolidge’s rise or his success as president. But he was most certainly the man for the moment. If you are inclined to believe in providence, his story ought to give you goosebumps.

“There is only one form of political strategy in which I have any confidence,” Coolidge wrote in his autobiography, “and that is to try to do the right thing and sometimes to succeed.”

And the man succeeded enough to remain the most popular president of the twentieth century.

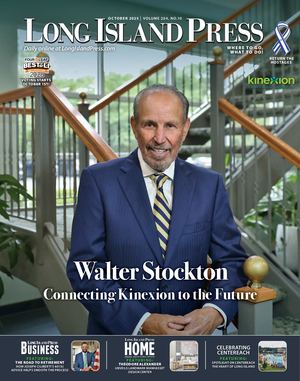

Cal, Our Pal: A Second Look At Calvin Coolidge

Calvin Coolidge taking the oath of office. (Photo courtesy the Library of Congress)