A century ago, Yankee Stadium opened, beginning a Golden Age that would last a half-century. In 1923, there were two professional sports that mattered, baseball and prizefighting. While the New York Yankees and New York Giants were on their way to a World Series match-up in October, the most extraordinary prize fight in American history also took place.

In 1923, Jack Dempsey was heavyweight champion of the world, a title he had held since 1919.

In South America, a young pugilist named Luis Firpo was making a name for himself. Firpo, a native of Junin, Argentina, had racked up a string of impressive victories, including those over prizefighters from Chile, Czechoslovakia, Italy, Austria, and the United States.

Dempsey, never one to duck a fight, accepted the man as his challenger for a Sept. 14, 1923 bout held in the Polo Grounds.

A crowd of 80,000 assembled for the fight. The bout didn’t last long. Still, fans got their money’s worth.

Firpo came out swinging, sending Dempsey to the canvas with a right cross. The story of the fight was simple: There was no standing eight count in those days. A prizefighter, once he flattened his opponent, could stand right over him and plummet the man time and again.

Which is what happened. Dempsey survived the knockdown. He struggled to his feet and managed to knock down Firpo seven times in the next minute and a half.

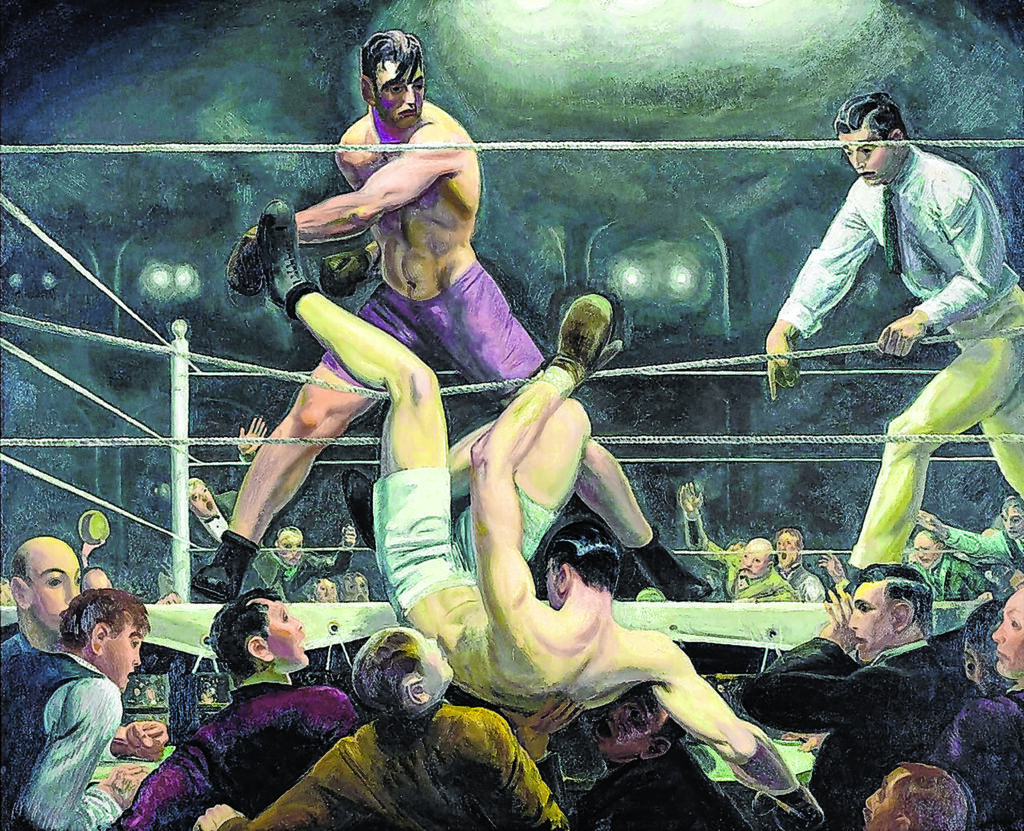

Incredibly enough, Firpo hung on. Undeterred, he knocked down Dempsey with a blow that was so fearsome that the champion was thrown clear out of the ring, landing, headfirst, in a pool of ringside reporters and photographers.

Dempsey didn’t quit either. He was assisted by the writers who shoved the champ back into the ring. Dempsey, too, benefitted from a rule that allowed fighters 20 seconds to recover from an outside-the-ring knockdown.

The first round, certainly the most eventful in boxing history, ended.

The second round was more of the same with Dempsey knocking down Firpo two more times, the last one at 57 seconds into the round, a knockdown that left the Argentinian on the canvas for good, ending the brawl in a victory for the defending champion.

The fight quickly passed into boxing legend. Dempsey held the title until 1927, when he lost to Gene Tunney, a battle where Dempsey went too late into his corner after a knockdown. The standing eight count was in effect and the champ had difficulty in adjusting to the new rule.

Firpo became a legend in both Argentina and the rest of South America, inspiring an interest in boxing that continues to this day.

The bout, too, became part of American culture. The George Bellows painting, Dempsey and Firpo, quickly became an iconic piece of artwork. A short film, Firpo-Dempsey, by Quirino Cristiani, was produced and released.

A decade later, three prominent sports personalities: Light-heavyweight champion Bob Olin, trainer Doc Robb and Madison Square Garden announcer Clem White all claimed that the bout was the greatest they have ever witnessed.

Great sporting events need great writers. That year, the young Thomas Wolfe, fresh from an MFA degree in playwriting from Harvard, was living in New York, teaching at New York University and hoping to sell his dramatic efforts.

Years later, in the posthumously published The Web And The Rock, Wolfe, in his pounding style, recalled the madness of the action:

That was no fight, no scheduled contest for a title. It was a burning point in time, a kind of concentration of our total energies, of the blind velocity of the period, cruel, ruthless, savage, swift, bewildering as America. The fight…resumed and focalized a period in a nation’s life. It lasted six minutes. It was over almost before it began. In fact, the spectators had no sense of its beginning. It exploded there before them.

And the reaction:

The crowd was composed…of men of the Broadway type and stamp, men with vulpine faces, feverish dark eyes, features molded by cruelty and cunning, corrupted, criminal visages of the night, derived out of the special geography, the unique texture, the feverish and unwholesome chemistries of the city’s nocturnal life of vice and crime. Their unclean passion was appalling. They snarled and cursed and raged at one another like a pack of mongrel curs. There were raucous and unclean voices, snarls of accusation and suspicion, with hatred and infuriating loathing, with phrases of insane mockery and filth.

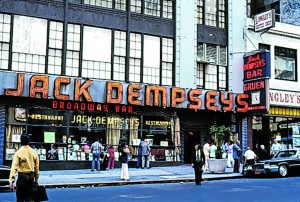

After his legendary fighting career, Dempsey, a native of Montana, settled in New York, where, from 1935 to 1974, he operated a popular saloon and grill, one featured in a memorable scene from The Godfather.

By the 1970s, New York had been overwhelmed by a crime wave, one that began in the early 1960s.

Jack Dempsey a crime victim? Fat chance. One day in the early 1970s, two would-be hoodlums tried to mug the man. They did. Dempsey didn’t give them the pleasure. He promptly slugged them both with one-two combinations and then went on his way.

The moral is simple: Don’t mug a former heavyweight champion of the world—even if he is an old man.