About one in eight women will contract breast cancer during her lifetime.

The good news is that breast cancer deaths have been decreasing steadily for several decades, falling by 43% from 1989 through 2020, according to the American Cancer Society.

Earlier detection, better screening tools, and markedly improved treatments have all contributed to this trend.

BREAST CANCER SCREENING

Screening mammography became commonplace in the 1980s, says Dr. Nina S. Vincoff, medical director of the Katz Institute for Women’s Health and division chief for breast imaging at Northwell Health. “This has led to earlier detection, when cancers are smaller and easier to treat, which translates to decreased mortality.”

Education around the need for screening mammography has also been highly effective. “It has been one of the most successful public health initiatives,” Dr. Vincoff says.

Several organizations provide slightly different screening guidelines, but Dr. Vincoff says research supports that the most lives are saved if women with average risk start screening mammography at age 40 and get yearly mammograms from that point onward.

“By the age of 25, all women should be talking to their doctor about their risk for breast cancer,” she adds. “No one should just assume that they have average risk. For women at high risk, screening may begin as early as age 25.”

Since mammography was first introduced, improvements in technology have also made it more effective.

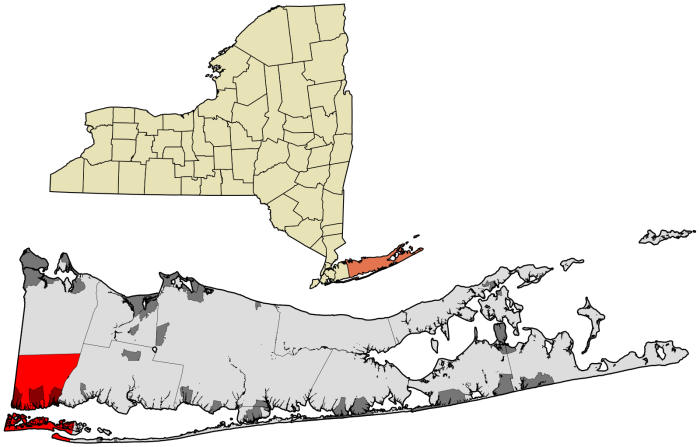

“We now have 3D digital mammography, which is also called tomosynthesis, and which can better detect tumors, especially in women with dense breasts,” says Dr. Brian O’Hea, chief of breast surgery at Stony Brook Medicine and director of the Carol M. Baldwin Breast Care Center.

Dr. O’Hea also points to the success of widespread campaigns to ensure that women are notified whether they have dense breasts and, if they do, that they can and should receive annual breast ultrasounds in addition to their mammograms. The FDA released new regulations this year requiring mammogram providers to inform women about their breast density. About 50% of women in their 40s, 40% of women in their 50s and 25% of women older than age 60 have dense breasts, according to the educational resource Dense Breast-Info.

There has also been a widespread effort to recognize women who are at a higher risk for breast cancer and to offer those women an enhanced screening protocol.

“We can now calculate a woman’s lifetime risk of developing breast cancer based on many factors, and women who have a lifetime risk of 20% or higher may also receive screening MRIs, which are typically given at six-month intervals to their annual mammogram,” Dr. O’Hea says.

But despite all these successes, many women are still not being screened appropriately. “Even in the most sophisticated areas, the percentage of women who are diligently getting their mammograms never goes above 70%, and in underserved areas, that number is probably closer to 50%,” Dr. O’Hea says. “So we have a long way to go.”

BREAST CANCER TREATMENTS

Breast cancer treatments have improved significantly. “Patients work with a multidisciplinary team, which may include a breast medical oncologist, a breast surgeon, plastic surgeon, radiation oncologist and others,” says Dr. Brittney Zimmerman, an attending physician in breast medical oncology at Northwell Health and an assistant professor at the Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell. “We work together and present at tumor boards to determine the best ways to take care of each patient.”

Breast medical oncologists prescribe medications, which may include antiestrogen therapy, chemotherapy and immunotherapy, and the care team closely monitors side effects.

“It’s an exciting time to be a breast medical oncologist, because there are so many options for effective treatments that also preserve quality of life,” says Dr. Zimmerman.

Treatment depends on the cancer’s stage and whether it is positive for estrogen receptors (ER), progesterone receptors (PR), or HER2 protein, which provide targets for treatment. Breast cancers with none of these targets are known as triple-negative.

About 70% to 80% of newly diagnosed breast cancers are hormone-receptor positive (ER and/or PR), according to the Susan G. Komen organization. In recent years, antiestrogen therapies have significantly improved survival for patients in this category. For patients with early-stage ER-positive, HER2-negative cancers, the Oncotype DX Breast Recurrence Score Test analyzes the genetics of the tumor and scores the likelihood of whether the cancer will recur in the future and whether the patient would benefit from chemotherapy, which can help inform treatment options. “With this test, we can spare 85% of patients from getting chemo and having to endure its potential short-term and long-term side effects, and identify the 15% who could benefit from it,” Dr. Zimmerman says.

For triple-negative breast cancers, chemotherapy was the only medical treatment option until recently. “But we have newer immunotherapy treatments which are very effective at treating triple-negative patients in addition to chemotherapy,” Dr. Zimmerman says. While chemotherapy kills both cancer cells and healthy cells, immunotherapy helps the body’s immune system identify cancer cells so it can attack them specifically.

HER2-positive cancers used to be associated with a poor prognosis, but now the treatments have become so effective that it’s actually viewed as beneficial for a tumor to have HER2 targets, Dr. Zimmerman says. “HER2-targeted therapies go directly to the cells that are expressing the HER2 and kill just the cancer cells,” she says.

Treatments have become not only more effective but markedly more tolerable.

“For people with relatives who went through chemo 30 years ago, it may be a scary word,” Dr. Zimmerman says. “But treatments and supportive care have gotten better, with anti-nausea medications and immune boosters to alleviate side effects to help patients maintain their quality of life and their normal activities.”