For decades, the “Where were you” question concerning Nov. 22, 1963, became a lasting pastime. It came up every November and whenever the presidency of John F. Kennedy was the subject.

The question became so prevalent that wits on all sides of the spectrum began to answer with an “I don’t know,” translated into “I don’t care” into “knock it off already.”

It matters. The cliche has long been End of the Innocence America. Being a cliche doesn’t make it wrong.

At the 1956 Democratic Party convention, Kennedy, then a Massachusetts senator, had his name placed in nomination as Adlai Stevenson’s running mate. He lost out to Estes Kefauver (D—TN). Kennedy left the convention as the hottest thing going in the party. In 1960, he won the nomination. As the fall election progressed, he held a healthy lead over his rival, Vice President Richard M. Nixon. As Election Day approached, that lead evaporated. Kennedy, ever the fatalist, commented to reporters that the country didn’t want a Catholic president after all.

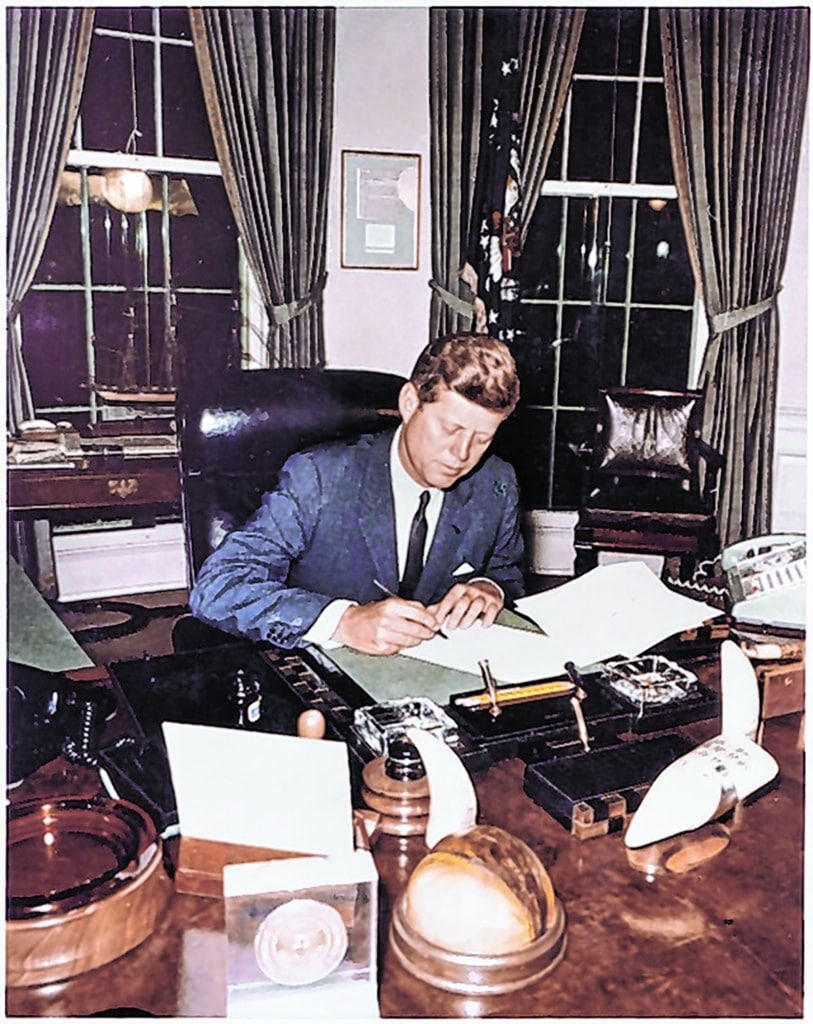

Kennedy did win a razor-thin triumph. The legend of his brief administration as Camelot only came about after his assassination. Other than the excitement in Cuba, Kennedy’s presidency represented a normal time for a normal nation. In the early 1960s, the U.S. economy boomed as before. Jobs and pay raises were abundant. Adults married young and started families. Kennedy was liberal as the term was then defined. He supported tax cuts, negotiated an arms control treaty with the Soviet Union, and nominated a conservative Democrat, Bryon “Whizzer” White, to the Supreme Court.

Cuba mattered. It was shocking to see America, at the zenith of its great power, allow a Soviet beachhead, one led by an anti-American demagogue just 90 miles from Key West. In early 1961, CIA-trained Cuban refugees attacked Cuba, hoping to overthrow Fidel Castro. Kennedy ignored advice from the super-hawk General Curtis LeMay, who counseled air support for the rebels. They didn’t get it, and Castro emerged triumphant. In 1962, Kennedy prevailed in having Soviet missiles removed from Cuba. The price was monumental. He agreed not to overthrow the Castro regime, a concession that was never reported in the media.

Did those two failures lead to the New Frontiersmen’s commitment to Vietnam? Lyndon Johnson escalated the war, but Kennedy first sent in actual troops. In 1983, on the occasion of the 20th anniversary of November 1963, Arthur Schlesinger maintained that if re-elected in 1964, Kennedy would have removed U.S. troops from that country. Was it true?

Undeniable is that Kennedy’s death was the most symbolic moment in modern American history. On the afternoon of Nov. 22, 1963, CBS was the nation’s leading television station, the “Tiffany” of broadcasters. On the air was a soap opera, a contended housewife dusting off a shelf in a contended America. Then, the interruption and the shocking news.

That week, Life magazine, which had a jaw-dropping circulation of 12 million, had planned to place Navy quarterback Roger Staubach on its cover. Instead, America had to endure John-John’s gut-wrenching salute to his slain father. The cynics have won. American life was never the same.

The columnist Joe Sobran claimed that since Kennedy’s death, the country had taken a frightening turn leftward. Was that true?

Kennedy was a reckless man but a prudent politician. There was arms control but also ambivalence towards civil rights. Both Kennedy and his younger brother, Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, held a negative view of Martin Luther King, Jr. Both wanted King to call off his June 1963 march on Washington. As a native of Massachusetts, Kennedy was sensitive over the American South, then wall-to-wall Democratic, from bolting to the Republican Party over civil rights. Kennedy supported civil rights, but he never pushed the issue.

Johnson was reckless in both his personal and professional life. In 1965, he increased the troop presence in Vietnam from 14,000 to 350,000 men, eventually reaching 500,000 troops. Johnson was a native Texan. He had no hesitation in steamrolling his old Southern Democratic friends on both civil rights and voting rights. The 1965 immigration bill transformed America in a way Ellis Island never did, from multiethnic to multicultural, from Robert Frost and Ernest Hemingway to “Hey hey, ho ho, Western civ has got to go.”

Did the Great Society promise more than its legislation could deliver? Guns and butter translated into a tax surcharge and inflation. By the summers of 1967 and 1968, crime and rioting had overwhelmed dozens and dozens of once-vibrant American cities. Such rioting even extended to such college campuses as the once-august Columbia University.

And so, the critical question. Would Kennedy, if re-elected, have withdrawn from Vietnam? If so, a much different 1960s. Thank God for presidents who prefer golf and Cape Cod- and other merriment- to remake an entire nation, much less the planet.