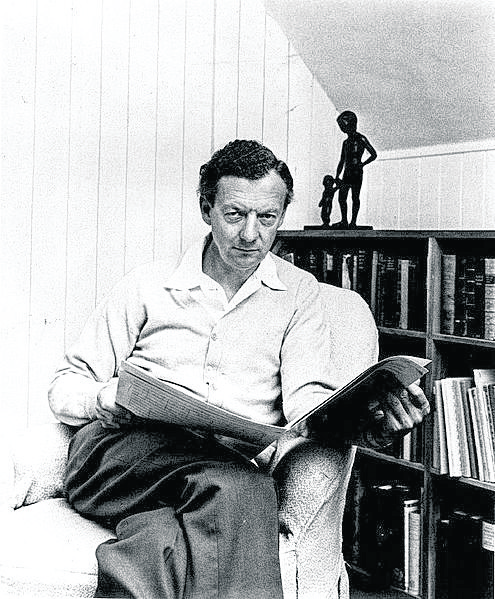

In the early 1930s, Adolf Hitler advanced his war on democracy as his troops marched relentlessly across Europe to seize power. Protesting against the violence unleashed by Hitler’s enablers were supporters of the British peace movement, whose members were influential artists, writers, musicians — and the gifted classical music composer Benjamin Britten, who composed Pacifist March for the Peace Pledge Union of England when he was in his mid-20s. Years later, he would receive a Grammy Award for War Requiem, his choral work that denounced the wickedness of war.

Britten’s goal was to confront social injustice and intolerance, including bullying and violence, through music. He created prolifically, and, as composer Aaron Copland told The New York Times, Britten “wrote some of the best music of our period and was undoubtedly England’s most distinguished and gifted living composer.” Much of that music was created during his Long Island years.

NO RADIOS IN THE HOUSE

Edward Benjamin Britten’s talent revealed itself before he could read or write; he composed songs in his hometown of Lowestoft, England, with the encouragement of his talented singer-pianist mother. By age 9, he had completed a string quartet and oratorio and by age 14, a symphony. He was allowed to listen only to live music; his father would not allow a gramophone or a radio in the house. As an adult, he found success composing operas, vocal music, film music, and orchestral and chamber pieces.

The composer’s antiwar beliefs, like his musical talent, had their roots in his early childhood, according to the U.K.’s Times Literary Supplement: When he was 3, in 1916, he heard the “threatening roar of an explosion” in a nearby field during the first World War; his uncle was killed in a battle on the Somme River. In boarding school, he refused to join the Officers’ Training Corps; Britten would later say that he was “already a pacifist at school.”

Over the years, he found recognition as an outstanding composer, conductor, and pianist. He often performed with one of England’s leading tenors, Peter Pears, after first meeting him in 1937. Initially, the two were partners only in the professional sense; in 1939, that partnership became romantic. It would last Britten’s entire lifetime. While Britten was outspoken about his pacifism, he never spoke publicly about his private relationship; he lived his life as an openly gay man even though homophobic laws in England were in place until partial decriminalization in 1967.

LIBERTY ON LONG ISLAND

In April 1939, seeking to escape the escalating conflict in Europe and pursue more promising musical opportunities, at Copland’s urging, Britten sailed to America with Pears. Critics faulted Britten for his move, criticizing him for turning his back on England in the face of the Nazi threat. Five months later, In September 1939, Hitler invaded Poland and Britain declared war on Germany.

In America, which had not yet entered the war, Britten found a respite; he would compose many works there, including his much-lauded, best-known opera Peter Grimes. He and Pears resided at the Amityville home of psychiatrist Dr. William Mayers and his wife Elizabeth Mayers, whom Britten described as “one of those grand people who have been essential through the ages for the production of art.”

Britten and Pears performed in November 1939 at Riverhead’s Hotel Henry Perkins, visited Copland upstate in Woodstock, and in 1940 moved into February House, a bohemian group residence in Brooklyn Heights, along with other creative artists. In Southold on Long Island, they befriended David Rothman, owner of the local department and variety store, who held weekly musical performances that included Britten, Pears and noted physicist Albert Einstein. Britten helped establish a musical advisory board for the Suffolk Friends of Music Orchestra in 1940 and became the orchestra’s musical director. Rothman arranged for Britten to be the accompanist for the Southold Town Choral Society, now the North Fork Chorale.

After three years, Britten and Pears found themselves longing for England. In 1942, as they sailed for Europe, Britten composed one of his best-loved Christmastime works: A Ceremony of Carols, a delicate yet powerful work called “thoroughly charming” by The New York Times. Back in England, Britten applied for conscientious objector status, arguing that he had devoted his life to creation and couldn’t switch to destruction. He was granted unconditional exemption from military service. He went on to compose works that often embraced themes of the outsider vs. a hostile society and the corruption of innocence.

Peter Grimes opened in London in June 1945, one month after Germany surrendered. Britten told Time magazine that the work embodied “a subject very close to my heart—the struggle of the individual against the masses.”

In July, a month after the opening, Britten and violinist-conductor Yehudi Menuhin performed recitals for concentration camp survivors. Both men said that the horrors they saw affected them for the rest of their lives. Britten was so shocked that he refused to talk about it until towards the end of his life, when he told Pears that it had colored everything he had written since.

Britten died of congestive heart failure in December 1976 at age 63 in Aldeburgh, England, near his hometown.