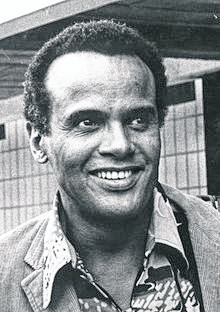

Harry Belafonte: Civil Rights Activist and Calypso King

He was raised in poverty, dropped out of high school, and survived being Black in a segregated society — before Black Lives Matter or Black History Month. He also became the first Black megastar and an internationally known humanitarian who broke racial barriers.

Harry Belafonte earned his title — “the king of calypso” — with Caribbean-flavored folk and pop music chart toppers like “Day-O,” “Jamaica Farewell,” and other hits, becoming in 1957 the first solo artist to sell more than 1 million albums within a year of release.

He generously established student scholarships on Long Island, where he headlined at sold-out shows and visited the Sag Harbor Hills, Azurest and Nineveh Subdivisions (SANS) Black historic district.

POVERTY AND POLITICS

Harold George Bellanfanti Jr. was a child of mixed ancestry: His paternal grandfather was a white Dutch Sephardic Jew, his Scottish grandmother was white, and his parents were Caribbean-born. Born in Harlem in 1927, he moved in with his grandmother in Jamaica in 1932. His Caribbean roots would later combine with his political education and civil rights awareness.

In 1940, he moved back to Harlem. His father, a chef on a banana boat traveling between the U.S. and the West Indies, was often away. At home, Harold’s mother struggled financially as a domestic worker, mending garments during the Great Depression. A devotee of Jamaican activist Marcus Mosiah Garvey, who worked to celebrate African history and culture, she introduced her son to Garvey’s philosophies.

The boy was a strikingly handsome teenager who carried himself with regal posture. But blindness in one eye and undiagnosed dyslexia caused him to fall behind in school; he dropped out of George Washington High School then enrolled in the U.S. Navy in 1943.

At that time the Armed Services still separated Blacks from whites. College-educated soldiers gave him political pamphlets about the Jim Crow laws enforcing or legalizing racial segregation: Blacks and whites could not play games together; Black children could not attend white schools; Transportation companies had to provide separate waiting rooms and ticket windows for Blacks and whites, and so on.

In 1945, returning to Harlem, he worked as a janitor’s assistant. Seeing a play at the American Negro Theatre, he was hooked. As he later told NPR, “What I had discovered in the theater was power: power to influence, power to know of others and know of other things.” While volunteering as a stagehand at the theater and studying acting at the New School, he met another actor-stagehand, Sidney Poitier, who was from the Bahamas. They would become lifelong friends and activists.

THE FIRST BLACK MEGASTAR

Belafonte was a struggling actor who was urged to sing by musicians at a Broadway jazz club, the Royal Roost. It was 1949, and the club needed an intermission setup act, reported Andscape.com. Backed by legendary musicians Max Roach, Charlie Parker, and Miles Davis, the raspy-voiced actor moved with grace and the reviewers praised him: “Although his voice was untrained, he projected something powerful and compelling on stage.” His performing career took off.

But a year later, he quit a gig in Miami because it meant singing to a white audience in a South defined by Jim Crow, according to Andscape.com. To bring about social change through folk music, he immersed himself in the New York folk scene. According to NPR, Belafonte was entranced by Woody Guthrie, Pete Seeger, and The Weavers, seeing folk music as a “populist outlet for a people’s experiences of oppression,” wrote VillagePreservation.org. In 1953, at the Village Vanguard in Greenwich Village, he sang the folk songs “Hava Nagila” and “John Henry” as well as the calypso tune “Matilda.” NPR described Belafonte as “charismatic and strikingly beautiful; unencumbered by a guitar and dressed in tight black pants,” he took folk music “up off its stool.”

He won a Tony for his Broadway musical performance and landed the starring role in a movie musical, against the 1954 backdrop of the Civil Rights Movement. Then came Calypso in 1956, his third album, celebrating the Trinidadian blend of Spanish, Creole, and African phrases.

BREAKING RACIAL BARRIERS

That same year, he befriended civil rights leader Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. They energized the movement to end segregation and eradicate prejudice through nonviolent protest. Like Belafonte’s friend Poitier, King and Belafonte broke taboos, using their talent, charisma and fame to effect social change; Belafonte contributed financially and helped fundraise to support the cause.

He won an Emmy Award in 1960 for his TV special, the first Black American to do so. But progress was uneven: The sponsor protested featuring Black and white performers together, and the Emmy winner was refused restaurant service in Atlanta because of his skin color.

Throughout the 1960s, he took his activism to speaking engagements with King, including in Great Neck and Rockville Centre on Long Island, and visited SANS. Starting in 1966 the calypso king performed often at the Westbury Music Fair, now the NYCB Theatre at Westbury. In 1992, Belafonte performed at the Tilles Center for the Performing Arts at LIU Post in Brookville to benefit his minority student scholarship fund. The Belafonte Family Foundation creates access and opportunity for the historically underserved and marginalized, across racial, gender, and economic lines.

His activism was lifelong: He urged people not to vote for Donald Trump in 2016 and in 2020, in his 90s, he called Trump “the flimflam man” in a New York Times opinion article.

Belafonte died in 2023 at age 96.