The end of June was her favorite time of year, when the sun didn’t set until 9:30 at night.

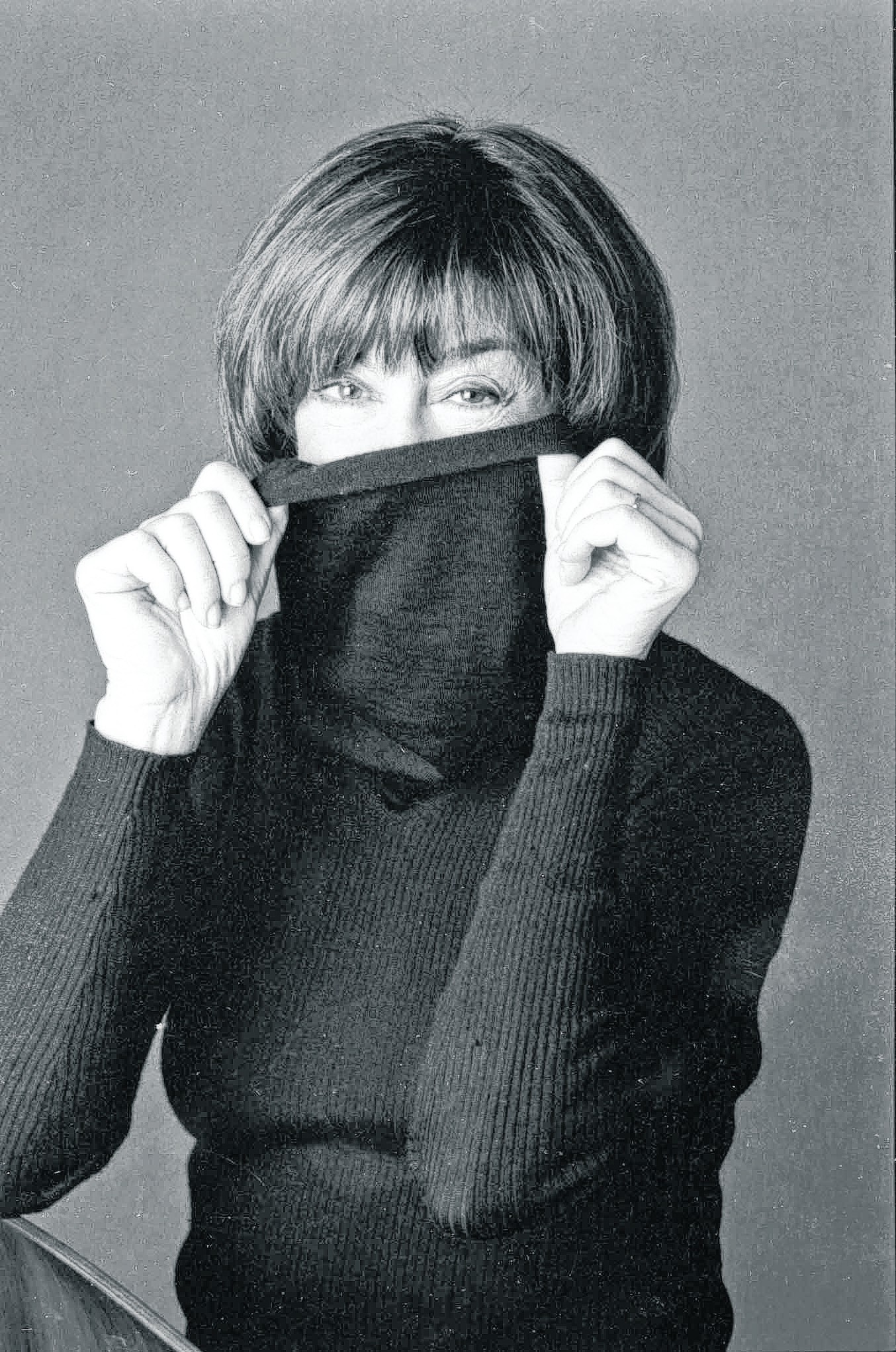

“You feel as if you will live forever,” is how Nora Ephron described her family’s summer vacations on the East End of Long Island in Springs, the picturesque neighborhood dubbed “Malibu East.” The journalist/screenwriter/director was one of many artists and others living the creative life who were drawn to the Hamptons as the perfect getaway from the dizzying pace of Manhattan, an idyllic setting where they could live less-scrutinized lives.

Despite surviving three marriages and divorces, she savored the joy of family life and captured the area’s ambience in her final essay collection, I Remember Nothing: and Other Reflections, writing, “On July Fourth, there were fireworks at the beach, and we would pack a picnic, dig a hole in the sand, build a fire, sing songs — in short, experience a night when we felt like a conventional American family (instead of the divorced, patched-together, psychoanalyzed, oh-so-modern family we were).”

Known for her witty, razor-sharp dialogue and skill at inventing strong female characters and laugh-out-loud lines for both the printed page and the movie screen, Ephron was a best-selling author and one of Hollywood’s most successful filmmakers — and one of its few working female screenwriter directors. She kept reimagining herself and her work won her major motion picture industry recognition, as with the blockbuster romantic comedies she wrote that included Sleepless in Seattle; When Harry Met Sally (inducted into the National Film Registry of the Library of Congress); and You’ve Got Mail.

KEEPING IT FRESH

Ephron was born in New York City in 1941 and raised in Beverly Hills, the child of two screenwriters who would later write two plays about their daughter. In the late 1960s, she started out as a researcher in the mailroom of Newsweek magazine, quitting after a year. She became a reporter and editor at the New York Post and an essayist for Esquire magazine and other publications, then wrote screenplays; one, which she cowrote, was Silkwood (1983), which won Ephron her first of several Academy Award nominations. Her first solo screenplay was Heartburn (1986), based on her bestselling novel which chronicled the 1983 breakup of her marriage to Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Carl Bernstein. She took to directing with Sleepless in Seattle (1993) and wrote the 2002 Broadway play Imaginary Friends. Her New York Times bestselling essay collection, I Feel Bad About My Neck, was published in 2006.

Writing in The Washington Post, journalist Sally Quinn said that Ephron, her neighbor in the Hamptons, was always “the director, whether she was on set or not .… she always told us what to do. Nora would find the perfect thing to eat or drink or root for, and we would all follow suit.” Quinn called Ephron “sharp and clever and witty and brilliant. But that was a total cover for the hopelessly sentimental person she was …. just look at the fairy-tale happy endings in her romantic comedies.”

Ephron constantly challenged herself and others to seek out opportunities. As she said in her commencement speech to the Class of 1996 at her alma mater Wellesley College, “I hope you will find some way to break the rules and make a little trouble out there. And I also hope that you will choose to make some of that trouble on behalf of women.”

In 2009, she told Ladies’ Home Journal, “Every 10 years or so there was a moment when I’d say, even subconsciously, ‘Is that all there is?’ You’ve got to find ways to keep it fresh for yourself. To do the thing, as they say, that is a stretch.”

SUMMER’S END

In I Remember Nothing, she wrote about what she called the magical Springs summers and how she once loved the sound of the beating wings of geese flying overhead in mid-July. But inevitably, in her mind, those sounds became a harbinger, portending that summer would not last forever.

“I’m sorry to say,” she recalled, “they became a sign not just that summer would come to an end, but that so would everything else. As a result, I stopped liking the geese. In fact, I began to hate them. I especially began to hate their sound, which was not beating wings— how could I have ever thought it was?— but a lot of uneuphonious honks.”

Continuing to take on yet another career stretch, in 2009 she helmed the film Julie & Julia as writer, producer, and director. For many, it was her best picture.

It was also her last: Three years later, at 71, she died of a rare blood cancer.