Many people are familiar with the Prize Patrol, a creation of a Port Washington-based magazine distributor Publishers Clearing House, once the largest private company on Long Island in terms of sales.

Over the years, PCH employees have visited homes and businesses, handing out thousands, and sometimes millions of dollars, to winners of the company’s sweepstakes competition. The company has always maintained signing up for magazines was not necessary to be in the sweepstakes. Winners are taken completely by surprise, as they are handed over a big check. The check presentations are covered by local television stations and broadcast nationwide.

The Patrol was first introduced in 1988, and from the start, it was a hit. The excitement it sparked turned PCH into one of the best — and wealthiest — private businesses in the county. In the 1990s, sales grew from about $30 million to $200 million. The company in that decade employed about 500 people.

PHC and its Prize Patrol were featured in Dateline NBC, 48 Hours and other national broadcasts. But those were the heydays of PCH, which gave hefty donations to charity every year and helped magazine companies sell their publications.

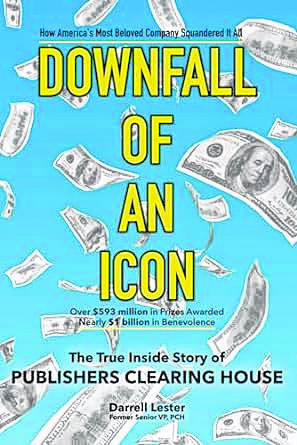

The ups and downs of PCH are the subject of a fascinating new book, “Downfall of an Icon,” by Darrell Lester, who spent 30 years at the company, retiring in 2003 as a senior vice president.

Lester, now 72 and living in Brookville, had a first-hand view of the company, founded in 1953 by Harold Mertz, in the basement of his Port Washington home. Mertz, a former manager of a door-to-door sales team for magazine subscriptions, was assisted in starting PCH by his wife, LuEsther, and their daughter, Joyce. Mertz, his wife and daughter are now all deceased.

Lester, soft-spoken and athletically trim from his days playing sports on Long Island, said in an interview with the Press, of his 200-page book, illustrated with photos of PCH executives and employees that:

“I had to write it,” he said. “So many great things happened. There were so many bad things, too. But it was my second home. The book is half about PCH and half about me.”

The early days were indeed thrilling.

By the late 1990s, sales had soared to about $1 billion and PCH had more than 1,000 employees.

The cast of characters who worked for the company fill Lester’s book, and he and they put in grueling hours and weekends to build the company up.

The most fun was had on the Prize Patrol, which once awarded $1 million to Martha McMillen, who lived in a small Missouri town. She was not home when the Patrol arrived at her front door, but her 18-year-old daughter, Courtney, was. Courtney answered a persistent knock on the door wrapped in a bath towel, dripping wet, and it was all filmed.

But things began to go sour in the next decade. That’s when PCH used the word “finalist” in its ad copy. A big argument broke out among senior executives about the use of that word. Its use was ultimately approved by then-CEO Robin Smith.

But the use of the word was misleading, said attorney generals in 14 states, who sued. PHC agreed to a $490,000 settlement and to change its practices.

Only a few years later, the entire industry, including PCH, was tarnished — and hit financially — when a competitor, American Family Publishers, became involved in a nasty fight with Richard Lusk, an 80-something-Californian, who flew to Tampa, Fla., thinking he had won $11 million. Lusk had received a mailing saying “You and another person were issued the winning number” for the prize.

When he arrived at an AFP customer service center in Tampa to collect what he thought was his winnings. Lusk was turned away. His son filed a suit, and a battle was on.

The Lusk incident went viral and sparked a storm of negative press stories, which impacted the entire sweepstakes industry.

PHC and others struggled to settle the lawsuits, but often failed as the law-enforcement officials battled for higher penalties and even reneged on settlement agreements.

In 1999, a U.S. Senate committee held hearings on sweepstakes promotions. PCH, Readers Digest, Time Inc., and AFP were called to testify. The hearings ultimately resulted in federal legislation requiring direct mail sweepstakes promotions to tone down their copy. Lawsuits continued against those in the industry, PCH included. They were finally settled in 2001.

Lestwer estimates that the company spent some $50 million in settling the suits against it.

PCH is now a shadow of its former self.

This past April, PCH said in a State Worker Adjustment and Retraining Notification Act, that it would be laying off nearly half of the 393 workers at its offices, in Jericho Triangle Headquarters, where it moved in 2023. The company said that the layoffs were “a strategic response to the reality of heightened postal, shipping and supply chain costs, along with the ongoing challenges that emerged from the post-pandemic world.”

It said also that the layoffs will not impact its sweepstakes. It said the company has given out $593 million in prizes over the years.

PCH in addition to the sweepstakes that market magazines creates digital games ad runs online contests.

Christoper Irving, a PCH spokesman said in an email. “Mr. Lester has not worked for Publishers Clearing House for over 22 years. His book recounts his own recollections of times gone by decades ago.”

“Over the past 22 years, Mr. Lester has had no contact or insight into the workings of Publishers Clearing House, where the company continues to delight consumers and award free-to-enter and win prices from coast to coast,” the statement said.

Lester looked downcast when asked about the company today. “The question I’m asked most,” he said, “is will they survive? I hope so.”