Many women who are diagnosed with breast cancer face the difficult decision of whether to have a lumpectomy with radiation or a mastectomy with reconstruction. With the availability of study results and advancements in genetic testing, there is more information than ever to help women make an informed decision about which pathway is right for them.

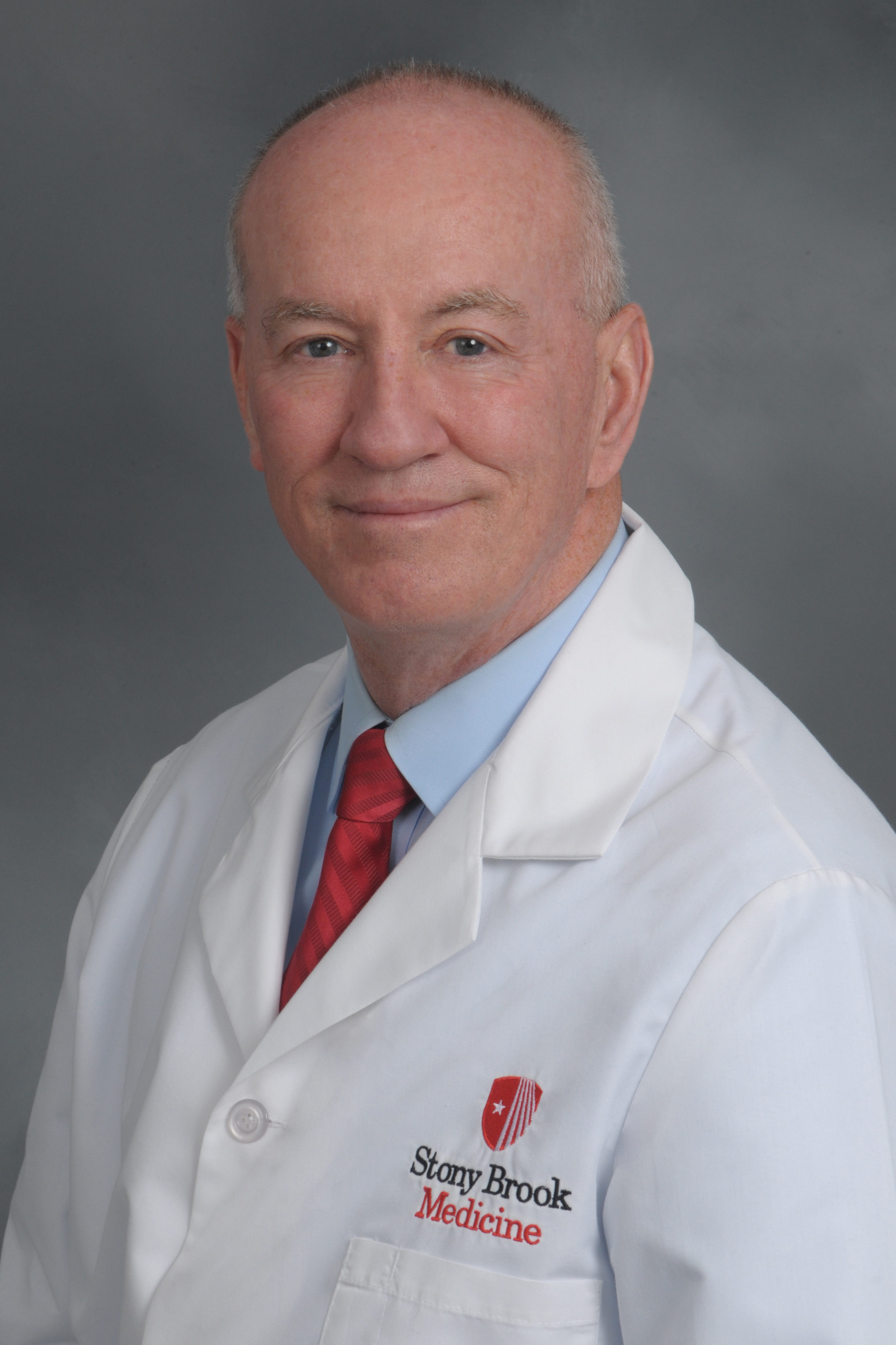

Surgery is the first treatment that most women diagnosed with breast cancer will undergo. “When I meet with a patient, I like to paint with a broad brush what she should expect going forward, so there will be no surprises down the road,” says Dr. Brian O’Hea, chief of breast surgery at Stony Brook Medicine and director of the Carol M. Baldwin Breast Care Center. In addition to the surgical options, O’Hea typically discusses the likelihood of whether the patient will also need other treatments, such as chemotherapy or estrogen therapy.

The main surgical options are a lumpectomy coupled with radiation treatments or a mastectomy with reconstruction. Based on many long-term studies of early-stage breast cancer, “women at average risk who get a lumpectomy with radiation have the same long-term survival rate as women who get a mastectomy,” says Dr. Sylvia Reyes, a breast cancer oncologist with the Zuckerberg Cancer Center of the Northwell Health Cancer Institute.

For each particular patient, there are several factors that go into deciding the best course of action, O’Hea says. “I always start by looking at whether I can create a pathway for breast preservation, and whether a particular woman is an excellent, medium, borderline or poor candidate for preservation,” he says. “I tell the woman what would be involved in saving the breast.”

An important consideration is tumor size versus breast size, says Reyes. The best-case scenario is a small tumor in a large breast, while a large tumor in a small breast would create obstacles to breast preservation. “If you have a 3 cm [centimeter] tumor in a triple D breast, that can be a lumpectomy, but for a 3 cm tumor in an A-cup size breast, a lumpectomy would be deforming,” Reyes says.

When a woman with large breasts needs to have a large tumor removed, she may opt for oncoplastic surgery to reduce the size of both breasts symmetrically at the same time as the lumpectomy. “Some women with large breasts like the idea of a breast reduction, and in some cases this could make a borderline candidate an excellent candidate for a lumpectomy,” O’Hea says.

Doctors also typically will do genetic testing and look at family cancer history in recommending treatment options.

“If patients test positive for the BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene mutation, the chance of the cancer returning is significant, and in most scenarios, a bilateral mastectomy would be recommended,” O’Hea says. There are additional gene mutations that put women at higher-than-average risk for a cancer recurrence, though not to the extent of the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes; in these situations, the risk would have to be evaluated on a case-by-case basis. It’s important to note that, even when a bilateral mastectomy is done, breast cells are not removed completely and there is no way to remove all risk of a recurrence, Reyes says.

A woman’s overall health is also a factor in the surgery decision. As a mastectomy is a larger surgery than a lumpectomy, it may not be the best option for women with certain comorbidities, such as uncontrolled diabetes, significant heart disease, or pulmonary disease, Reyes says.

Patient preference is also an important factor. Some women diagnosed with breast cancer have a gut instinct to have a mastectomy, while others are highly motivated to choose a lumpectomy.

“Some women identify very personally with their breasts as being an important part of them being female,” Reyes says. “A lumpectomy allows women to continue to have sensation and nipple function. It can be psychologically traumatizing to no longer have your breasts, and a small amount of women will have chronic pain postmastectomy. It’s not a decision to make lightly.”

Women who choose to have a mastectomy also need to consider which type of reconstruction they will have. One option for many women is a deep inferior epigastric artery perforator (DIEP) flap surgery, which involves taking tissue from the abdomen to recreate the breast, Dr. Reyes says. Another option is implant surgery. While the DIEP flap may be more appealing to women who do not like the idea of having foreign implants in their body, it may not be an option for very thin women. It also is a longer surgery, with a longer recovery period.

A DIEP flap is typically done at the same time as the mastectomy. In most cases, implant surgeries are done in two stages. A tissue expander is placed during the mastectomy. Then in office visits, the plastic surgeon gradually fills it with saline through a small valve under the skin, allowing the skin to expand slowly. Then the patient will go back for a second surgery to have the implants put in place, Reyes says.

When choosing a surgery plan, shared decision-making between women and their doctors is key, says O’Hea. “If you’re told you’re not a good candidate for a lumpectomy, ask your doctor if anything can be done to make you a good candidate,” he says. “And if your doctor is recommending a lumpectomy and it doesn’t feel right, you shouldn’t feel bad about yourself if you choose to have a mastectomy.”

October is Breast Cancer Awareness month. Get screened at a location near you.