I was not quite 9 years old when I said “Good Night” to my mother for the last time.

She was ill in bed, and I went upstairs to my little room on the third floor of my grandparents’ house, where we were living in Mount Vernon. The medical bills had resulted in bankruptcy and the loss of our home in New Jersey.

During the night, I heard voices on the second floor and called down to ask what was happening. I was told to go back to sleep but wish that I hadn’t. For the first time, I would not be able to say “Good morning” to my mother. That was 77 years ago this coming Jan. 30.

The next day, I learned that my mother had died from bone cancer. The disease, caused by the radiation treatments intended to find needles left in her body following surgery, had kept her bedridden for more than a year.

Last winter listening to a Met Opera special with Bryn Terfel in Wales singing holiday music, I walked to a windowsill arrayed with family photographs. I picked up her picture, and tears came easily.

Memories followed: memories of her reading to me while I sat on the grass and she leaned against a tree, visiting doctors, one of whom encouraged my interest in medicine and biology, riding a train to New Hampshire to visit relatives, helping her in the kitchen by kneading the margarine after bursting its color pellet, and more.

I thought of the memories she missed, milestones of schooling and career, holiday celebrations with friends in Floral Park, and the children and grandchildren for whom she is a picture in a frame.

I also thought of other days she might have seen, including more of her poems published, more amateur theater roles, and more volunteer work.

My mother was an independent spirit, perhaps disappointing her highly schooled father and the two sisters who married “well.” I never got to know those aunts, except for an occasional visit to one who lived in New Jersey.

However, I often stayed after school at the home of a third aunt, an accomplished organist at the First Presbyterian Church.

After our mother’s death, my sister and I went to live with different families of aunts and uncles for a year and two summers.

Living in a different state where I was noticeable for my height and different accent, I too learned to be independent. I rode the train from New York City to Boston by myself.

My uncle was chief engineer at a radio station, and I participated in its quiz programs. I attended summer camp and learned outdoor skills that weren’t needed in Mount Vernon.

My independence became important when I returned home and attended Grimes Elementary School at 10th Avenue and Second Street on the other side of the city. I walked to school and ate lunch at a nearby restaurant, as it was too far to walk home and back, and the school lacked a cafeteria.

During Junior High, I began working, first as a “pin boy” at a Methodist Church’s bowling alley and then as a Printer’s Devil at a small print shop down by Hutchinson River Parkway. Independence was also important during my summer job at Willson’s Woods Pool.

I chose the “swing” shift so that I could work two nights a week in the filter house after the pool closed and could read without interruption.

While at Washington Junior High, I began “acting out” and was told that it was a delayed reaction to my mother’s death.

I thought it had to do with being bored and hanging out with some rebellious kids. The antique dealer near the school whom we had been harassing took me in as a stock boy and became a mentor. I settled down and, while I stopped my clarinet lessons, became active and then a

leader in a church youth group, first in Mount Vernon and then in all of Westchester County.

I walked to A.B. Davis High School each day from just below Third and Third and remember stopping in Hartley Park from time to time. When I look through my yearbook, I am reminded of classes with favorite teachers. During a high school reunion, I reminisced with old friends.

When we arrived at the second floor of Davis during our tour, I remembered where I was standing when Joe Leone, my former biology teacher and then a guidance counselor, asked why I had not signed up for the SATs. My father had not gone to college and was not attuned to such matters.

A mentor and a teacher guided me and inspired my interest in education. At Adelphi, we placed signs saying “Others” (respect others, consider others, etc.), something I witnessed and learned from at the camp outside of Boston that I attended when I was 10.

At different times over the years, I would think of my mother and wish she could see how I had grown up and that I could have seen her grow old. While my “Good Night” was never followed by “Good Morning,” my love and memories remain vivid.

_______

Ann Frances “Peggy” Waterman Scott, January 16, 1903 – January 31, 1948.

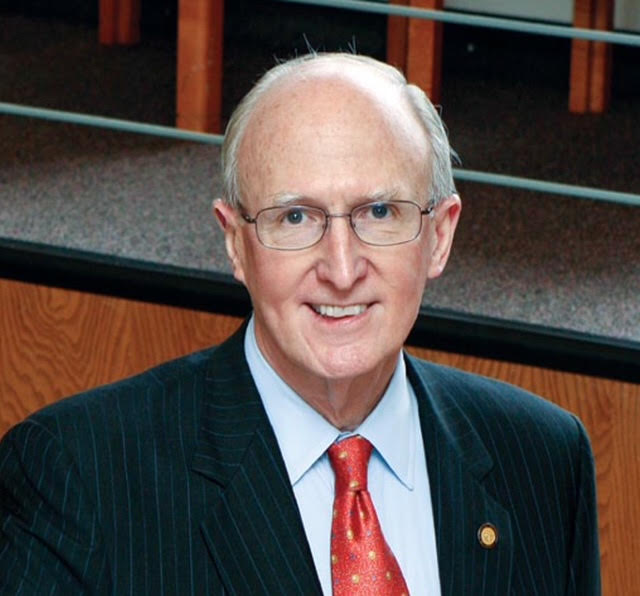

Robert A. Scott, president emeritus, Adelphi University; Author, “How University Boards Work,”

Johns Hopkins University Press, 2018, Eric Hoffer awardee, 2019; co-author, “Letters to Students:

What it means to have a college degree,” Rowman & Littlefield, 2024.