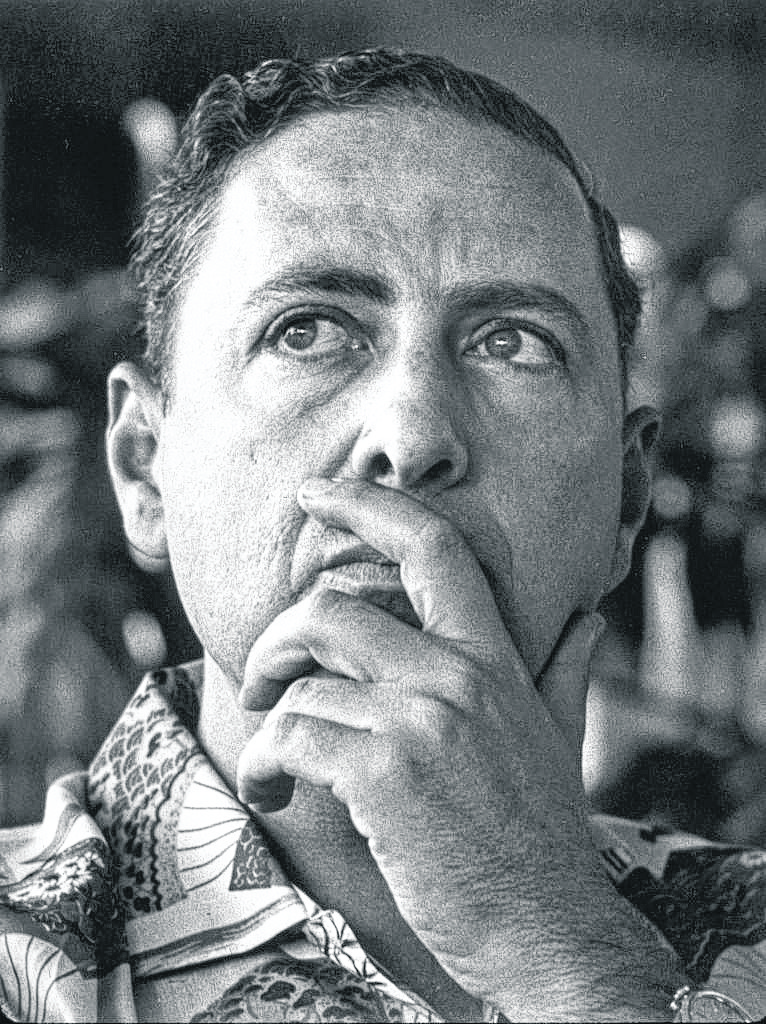

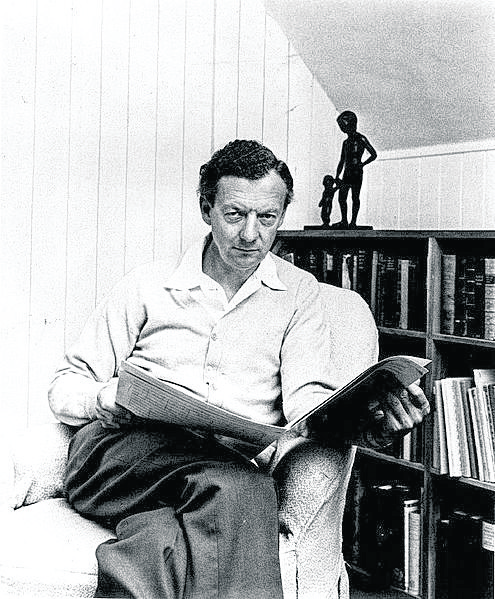

In an attic room of a little house in the village of Northport on Long Island’s North Shore, in 1951, a young, unknown writer from Great Neck wrote several novels and plays. He also researched and outlined the epic war tome “The Caine Mutiny,: his third novel, which won him the Pulitzer Prize in fiction in 1952. That honor came just in time: He was ready to give up literature as a career because his second novel had been poorly received.

Winning a Pulitzer was quite an achievement for 35-year-old Herman Wouk. But perhaps more important to the author — and to others — was his founding of the Fire Island Synagogue, the only temple on the three-block-wide, car-free barrier island off the South Shore of Long Island.

White Protestants Only

The temple’s first organized prayer service took place the same year Wouk won the Pulitzer. With readings in both English and Hebrew in hopes of appealing to nonorthodox Jews, the service was held in the living room of Wouk’s Seaview home at B Street and the Atlantic Ocean; he made a successful appeal to the families there for funds to construct a building.

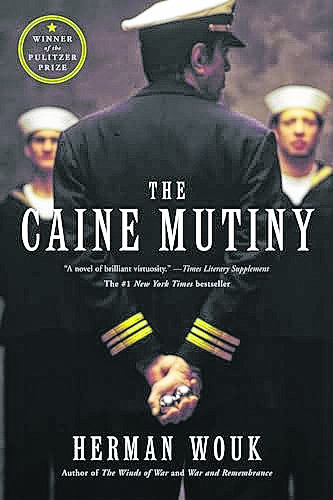

Today, 93 years later, that synagogue is still thriving, and his prize-winning prescient novel is more relevant than he could have imagined: Caine is the story of a tyrannical, erratic leader who blames everyone else for his questionable decisions. Described by The New York Times as a “crackling drama on the high seas,” the story is driven by a ship captain who steers his minesweeper toward a typhoon. He is relieved of his command by junior officers who later face court-martial.

Wouk never took the easy route, choosing to write about themes such as war and the Holocaust. And the route to founding a temple was not easy, given the prevalent discrimination of those years: As “The Jerusalem Post” reported, the Seaview section was restricted to white Protestant homeowners until 1928, when the ban was lifted. From the 1940s through the 1960s, Jews began arriving in the laid-back beach town.

In 1946, Wouk settled on Long Island in Northport; vacationing on Fire Island in the summer of 1952, he and Rabbi Adrian Skydell and others agreed that the area lacked an Orthodox element. They sought to discover if the community had enough interest to start a synagogue.

The Jewish Horizon reported that there was enough interest, as illustrated by Wouk’s announcement: “We are going to hold services in my home at 9:30 p.m. next Shabbos [the Jewish Sabbath], please G-d. Tell all your friends about it.” Later in life, everywhere he lived, including the Virgin Islands, Washington, D.C., and Palm Springs, Wouk worked to set up Jewish study and prayer groups.

Writing in longhand

Wouk‘s faith, like that of many others, was rooted in childhood: His immigrant parents from Belarus instilled a love of Judaism in their three children. He recalled that his father loved Yiddish literature and read to the family each week. Growing up in the Bronx, the child born in 1915 had read most of Mark Twain‘s work by the age of 11.

“I was thus soaked in the best kind of writing from childhood,” he said in a 1966 interview with Writers Digest. Excelling in school, he attended Columbia University and wrote for university publications; he graduated at age 20 and became a staff writer for radio comedian Fred Allen in 1936.

In 1947, his first effort, “Aurora Dawn,” was published. He had written it in longhand at sea, after enlisting in the U.S. Navy during World War II. His wartime experiences were the basis of “The Caine Mutiny,” written four years later. HIs subsequent best-selling page-turners “enthralled millions of readers in search of a good story, snappy dialogue and stirring events, rendered with a documentarian’s sense of authenticity and detail,” wrote The New York Times. But the critics’ reviews were often brutal. As Forbes magazine described their reception, “… the literary world, full of self-importance, … never decided if he was a guy who turned out potboilers or a real literary man.”

Choosing to spend time in two small Long Island towns, Wouk was described as reclusive, telling Writers Digest, “It seems unarguable to me that a quiet remote place is best for writing.” At the same time, he was also prolific: He published 15 novels, many of which were historical fiction; some were adapted into television movies or plays. He was, as Forbes put it, “first and foremost a storyteller” who could compellingly write about war, entertainment, business or just ordinary everyday life and make it seem interesting.

In 2012, at age 97, he was still at it, publishing “The Lawgiver,” a comic novel made up of text messages, emails, Skype transcripts, what have you. He was working on another book when he died in 2019 at age 103.