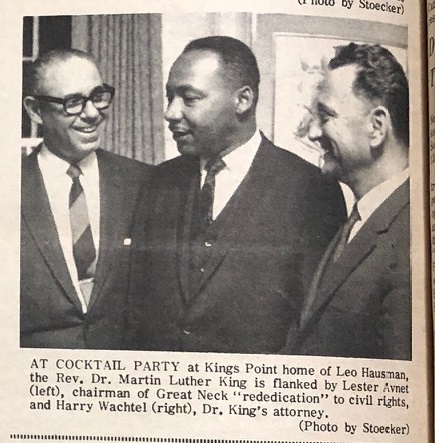

Martin Luther King Jr. made several trips to Great Neck in the 1960s, where his relationship with the Jewish community flourished, leaving an enduring legacy of interfaith solidarity and civil rights advocacy. These visits reflected King’s broader efforts to build alliances across racial and religious lines during the height of the Civil Rights Movement.

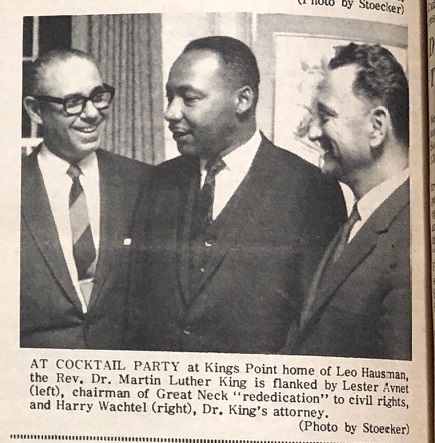

Great Neck became an unlikely yet vital waypoint in King’s journey for racial equality. At a time when segregation and racial violence plagued much of the country, the Jewish community in Great Neck opened its doors to King, providing both a platform for his message and financial support for the movement. Synagogues, civic organizations and individual families in the area played an active role in hosting King and amplifying his calls for justice.

One of King’s most notable connections in Great Neck was with Rabbi Jacob Philip Rudin of Temple Beth-El, a congregation that had long championed social justice causes. Rudin and King shared a mutual belief in the prophetic tradition of speaking out against oppression. In his speeches at Temple Beth-El and other venues in Great Neck, King often drew on Jewish teachings and historical experiences, particularly the Exodus story, to highlight the shared struggles for freedom and dignity faced by African Americans and Jews.

King’s visits to Great Neck were not merely symbolic but part of a deliberate strategy to build a broad coalition of supporters. He understood the importance of engaging affluent, socially conscious communities that could provide moral and material support for the movement. The Jewish community, many of whom were descendants of immigrants who had faced discrimination, resonated deeply with King’s message. This solidarity was evident in the financial contributions raised during King’s appearances, which were used to fund initiatives like voter registration drives in the South.

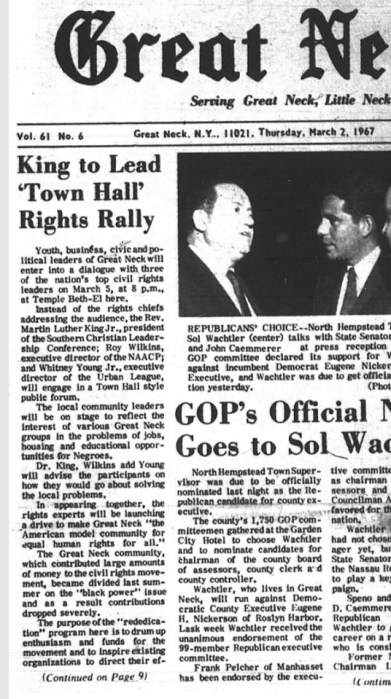

The relationship between King and the Jewish community in Great Neck also reflected a broader alliance between Black and Jewish leaders during the Civil Rights Movement. Organizations like the NAACP and the American Jewish Congress frequently collaborated and Jewish activists played prominent roles in pivotal events like the 1963 March on Washington. King often spoke of the deep moral and historical ties between the two communities, acknowledging the contributions of Jewish allies who risked their lives for the cause of racial equality.

Despite the warmth and mutual respect that characterized these interactions, tensions occasionally arose, particularly as the movement evolved in the late 1960s. The rise of Black Power, emphasizing self-determination, sometimes clashed with the liberal integrationist ideals espoused by many Jewish allies. However, King consistently emphasized the importance of unity and dialogue, urging both communities to focus on their shared commitment to justice.

King’s visits to Great Neck exemplified his ability to transcend barriers and build bridges. They underscored his vision of a “beloved community” where people of all backgrounds could unite to confront injustice. His relationship with the Jewish community in Great Neck remains a powerful testament to the enduring strength of interfaith collaboration in the fight for civil rights.

Newspaper archives, including “Great Neck Record,” and “Great Neck News,” have been preserved and are available online, on microfilm at The Joan and Donald E. Axinn Library at Hofstra University and in the local history room at Great Neck Library (159 Bayview Ave. in Great Neck).