This story is the fifth in a series by Schneps Media Long Island on the opioid crisis in Nassau County.

The Family and Children’s Association’s Sherpa program offers a unique service as peers in recovery meet individuals at various stages of substance use where they are at. While this model is credited for its high success rate, program coordinators say that even more can be done.

“What makes this program so special is that it is a peer-led program,” said Jaymie Kahn-Rapp, assistant vice president of harm reduction and recovery. “Individuals with lived experience, individuals who’ve been in the position of those we serve are those who are providing the care.”

The Sherpa program is a team of certified recovery peer advocates who meet with individuals and families in hospitals and the community who are at risk of substance use. Peer advocates then connect these individuals with the services they identify as needing.

In 2024, Sherpa served more than 1,800 individuals. Of those individuals, more than 95% were connected to a service that met their needs. But Kahn-Rapp said there are more than 1,800 Long Islanders who need support.

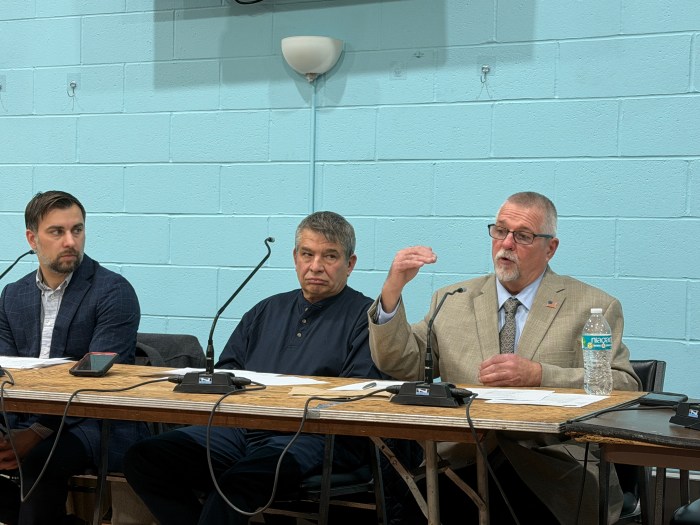

Sherpa Program Director Bradley Baer said that at the program’s core are the crisis recovery peer advocates who visit individuals at their bedside at local hospitals, connect them to services, and advocate on their behalf. While Baer now serves as the program’s director, this is where he started.

Baer, who has been in recovery for more than six years, became a certified recovery peer advocate through FCA. He said he found purpose in the work, starting out as the boots on the ground in the program and visiting hospitals to visit individuals in need.

Kahn-Rapp said what they are fighting against is the disconnect between healthcare providers and the experience of drug users. She said no matter how skilled the provider is, individuals can still be skeptical about their understanding of drug use.

“But our peers who engage individuals bedside at NUMC can say: ‘I actually have been in that bed. I get where you are,’” Kahn-Rapp said.

The Sherpa program started with $30,000 and a partnership with Catholic Health hospitals to connect with individuals who overdosed, were revived by Narcan and brought into a hospital. In these instances, a Sherpa representative was contacted to then meet with the individual to discuss services.

What they found, however, was that many hospital staff were identifying individuals at risk for the program who did not come in because of a substance use issue. Sometimes this was an individual with a broken leg who exhibited signs of substance use, Kahn-Rapp said.

So the program adapted.

But not everyone revived by Narcan chooses to be admitted into a hospital, Kahn-Rapp said, so the program had to adapt again by seeking out these individuals further.

While the program was formed around addressing the opioid crisis, Sherpa works with all individuals at risk regardless of the substance involved.

The program has grown immensely, expanding to all Catholic Health hospitals, Suffolk Courts and a multitude of community partners to reach all individuals who would benefit from connecting to substance use services.

The main goal of Sherpa, Baer said, is to break down stigmas surrounding substance use disorder. He said this is done by advocating directly to providers and community education.

But one of the program’s biggest assets is what Baer and Kahn-Rapp called “meeting people where they are at.”

Kahn-Rapp said this program is one of the most impactful because it connects with individuals who are not seeking services but are at the most risk.

“Through engagement of individuals with lived experiences, we’re able to connect them to live-saving services,” Kahn-Rapp said.

Baer said they interact with individuals with varying needs, from those who don’t need recovery to those in the pre-contemplation stage and those ready for it. By meeting them where they are, Baer said they can connect them to services that fit their needs.

For someone who uses drugs casually and may not need to go into recovery, these services could be STD and STI testing to mitigate health risks.

Because recovery looks different for everyone, the Sherpa program is not designed to tell individuals what they need. Instead, it is to connect them to the resources they identify as needing.

“We’re not telling them ‘you should stop using,’” Kahn-Rapp said. “We’re saying, ‘What is it that you want? What is it you need?’”

Baer called it “person-centered,” a more successful form of connecting individuals to long-term recovery.

“It really is a different experience when somebody who is on the other side comes to meet with you and can relate their past experience,” Baer said.

Looking forward, Kahn-Rapp said the is now planning to expand its grassroots services to engage with individuals who are isolated from the areas it already serves.

But Kahn-Rapp said they are planning to build off the foundation they’ve already established, letting the community lead them down the path that will better serve them.

Read more from this series:

Turning pain into purpose: Mother takes OD prevention into own hands after son’s death

Glen Cove grandmother channels grief into drug overdose prevention advocacy

After 70 years of service, the need for LICADD continues to grow amid local opioid crisis