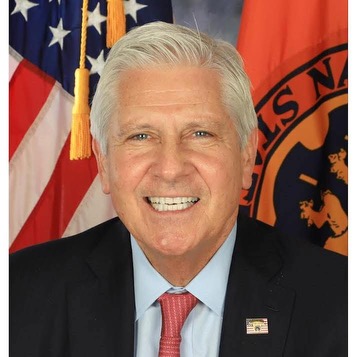

Suffolk County now has a county executive who understands the need to have treated wastewater put back into the underground water table on which the people of Long Island depend on as their “sole source” of potable water instead of dumping it in nearby waterbodies. And Ed Romaine is getting support from the Suffolk County Legislature.

Meanwhile, in Nassau County what is dubbed “water reuse” is beginning to happen, says John Turner, senior conservation policy advocate at the Seatuck Environmental Association. But much more needs to be done.

Some 88% of Nassau is sewered and from its sewage plants on its north and south shores, wastewater is sent through outfall pipes into adjacent water bodies. And the water table under Nassau has been lowering. Hempstead Lake, says Turner, is now spoken of as “Hempstead Puddle” and Valley Stream, “Valley No-Stream.”

Read more: Concern for Long Island’s groundwater sustainability prompts study

Further, an 83-page hydrology report done by the U.S. Geological Survey was released in 2023 about the underground water table below Nassau, which reported that it is now “under stress” with saltwater intrusion moving in as the amount of freshwater in it is depleted.

One can go back to the late 1800s and how Brooklyn lost its potable underground water supply — by over-pumping from the water table below it and consequent saltwater intrusion, along with pollution — and became dependent on an upstate reservoir system developed by New York City. On allowing Nassau to get water from these reservoirs, Turner says “New York City has not been welcoming Nassau County with open arms.”

But in Nassau, the Great Neck Water Pollution Control District is now using recycled wastewater to wash down equipment and there is interest in using treated wastewater to irrigate close by golf courses.

In 2023, a Long Island Water Reuse Road Map & Action Plan was advanced by the Islip-based Seatuck Environmental Association. The plan identifies 50 golf courses in Nassau and Suffolk within two miles of wastewater treatment facilities and thus available for reuse, along with other sites including “greenhouses, as well as for lawns at educational campuses” and “commercial centers.”

But how is this to be paid for?

In Suffolk last year, funding for “water reuse” came with passage in a countywide referendum on a Suffolk County Water Quality Restoration Act, increasing the county sales tax by l/8th of a percent sales tax to raise money to build sewers and install high-tech Innovative/Alternative septic systems — and finance, as the measure stated, “projects for the reuse of treated effluent.”

Funding for “water reuse” in Nassau could come from the Clean Water, Clean Air, and Green Jobs Environmental Bond Act that was approved in a statewide referendum in 2022 to, according to the state’s Department of Environmental Conservation.

There is $650 million allotted, says the statement, for “water quality improvement and resilient infrastructure.” Can Nassau’s delegation to the State Legislature and the governor get the DEC to free up some of those millions for “water reuse” in Nassau?

A breakthrough in Suffolk in water reuse happened in 2016 when treated effluent from the Riverhead Sewage Treatment plant began being used to irrigate the adjacent Indian Island County Golf Course to offset dumping it into the Peconic River.

Suffolk is now 25% sewered. Romaine wants sewage systems in Suffolk doing recharge. He says: “We’re not as stupid as they were years ago where all they did was take that outfall pipe and send [wastewater] out to the ocean or the Long Island Sound.”

Romaine was in December at the Bergen Point Wastewater Treatment Plant in West Babylon, built to send 30 million gallons of wastewater a day into the Atlantic, to announce having treated effluent from the plant used to irrigate an adjacent county golf course and used within the plant.

“This,” he said, “is one of 10 county wastewater treatment plants that we are currently considering for water reuse. By utilizing what otherwise would have been a byproduct, we can decrease the pressure on our aquifer by hundreds of millions of gallons a year and even help recharge the aquifer.”