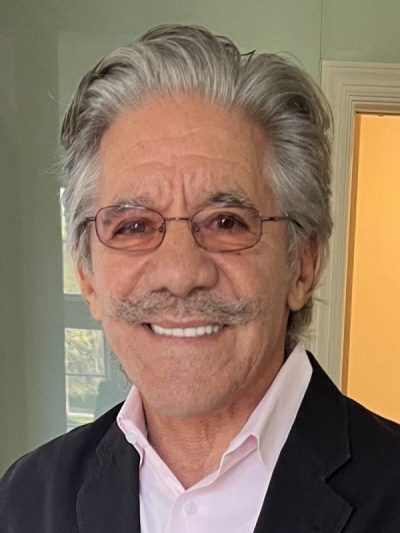

One of life’s great joys has been meeting and occasionally befriending the planet’s movers and shakers. Presidents and prime ministers from Netanyahu to Arafat, Clinton to Carter, and Castro to Trump are larger-than-life titans who have shared wisdom and advice.

Many come from show business: Elvis Presley, Frank Sinatra, Michael Jackson, Barbra Streisand, Paul McCartney, Mick Jagger; each name dropped conjures specific historical anecdotes that infuse this old man with delightful memories.

High in my pantheon of heroes is the late great John Lennon, who, with wife and partner Yoko Ono, is the subject of “One to One: John & Yoko,” a big new documentary that counts their son Sean Lennon among its executive producers.

The biography focuses on the Lennons’ sojourn in New York City during the tumultuous years 1971-1972 that transformed their lives and made music history.

When the film begins, John and Yoko have become artists-in-residence down on Bank Street in the West Village. At the time they were being pursued by federal immigration authorities seeking to deport them.

The Nixon Justice Department at the time was using a six-year-old minor misdemeanor conviction for marijuana possession to label them undesirable aliens and to justify removal.

Fighting deportation and eager to campaign against the war in Vietnam, the real reason Nixon wanted them out of the country, John and Yoko dabbled in protest from their bed in their Bank Street apartment.

They were there when they reached out to me because they were deeply moved by a story I was investigating, my coverage of Willowbrook, the world’s largest institution for the mentally disabled.

When they summoned me to their apartment, John and Yoko were hungry for information about Willowbrook, principally how it came to be one of the modern world’s worst such facilities, filthy, unhealthy and often deadly for its residents.

That was in January. John and Yoko agreed to stage a benefit concert the following summer.

I offered to mobilize the families of the residents to demand better conditions. The concert and a day-long festival in Central Park for residents in which they were all paired with a volunteer came to be known as One to One. We wanted to emphasize the need for individualized care for each disabled person.

The event was a spectacular success, helping jumpstart the growing movement to provide each disabled person with the resources they need to live the fullest lives possible, ultimately leading to the Americans with Disabilities Act.

The Lennons’ iconic performance would be John’s final full concert after leaving the Beatles.

On a sunny fall day in 1980, I ran into John and Yoko after falling out of touch with the power couple several years before. They were happily pushing their then five-year old son Sean in a stroller along Central Park West near my W. 64th Street apartment. It was a sweet meeting in which we shared memories of the event and about John’s immigration hearing in which I testified.

John was of course found to be a desirable alien after all.

Several weeks after that meeting, an evening was punctured by shots fired a few blocks uptown.

The gunfire was not completely unusual along Central Park in those days, so I wrote it off until I got a call from my ABC News assignment desk. They wanted me to come in to cover the murder of my friend John Lennon, who had been shot outside his apartment in the Dakota on W.72nd Street.

John was killed at the age of 40. It has been almost 45 years. Imagine how much music we lost because of Mark Chapman’s senseless attack.

Check out “One to One, John and Yoko,” a wonderful film.